A 2002 cult classic takes one travel writer on a quest to learn more about the Sikh faith, bringing with it unforeseen challenges and goodness.

A 2002 cult classic takes one travel writer on a quest to learn more about the Sikh faith, bringing with it unforeseen challenges and goodness.

If there’s one film that resonated with an entire generation of young women from the South Asian diaspora, it’s Bend It Like Beckham. I relished the on-screen representation of our lives, relating to the lead character, Jess Bhamra, trying to balance her Punjabi identity with the social norms of life in West London. I cheered her on as she dreamt of someday playing football professionally. And I found humor in the old-fashioned priorities of her traditional mother. In my case, the film also instigated an inexplicable curiosity about Sikhism.

Growing up in the very diverse city of Dubai—there were 83 different nationalities at my high school alone—I had been exposed to myriad religions and cultures. But I knew very little about this faith, besides the fact that Sikh men wear turbans.

Through movie scenes depicting fervent prayers and animated hand gestures in the direction of a bearded man’s portrait above the fireplace, I slowly put two and two together—that was Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism. At one point, Jess even credits him for her athleticism, saying, “I didn’t ask to be good at football. Guru Nanak must have blessed me.” A reference to something called ‘langar,’ however, went over my head. Bear in mind that Bend It Like Beckham was released in 2002, in the early days of instant online searches.

It wasn’t until 18 years later that I heard the term ‘langar’ again, albeit in a very different context. I spent most of 2020 doom-scrolling, repeatedly encountering reports about the Sikh community of India as a result. Dubbed “coronavirus warriors,” Sikhs opened their langars—their community kitchens—to provide free food to the needy as well as oxygen cylinders and ambulance services to COVID-19 patients, no questions asked. The crisis came and went, but those headlines about the relentless ‘seva’ (selfless service) carried out in the langars of the gurdwaras (Sikh temples) somehow stayed with me, piquing my interest in Sikhism all over again. And that’s precisely why I ended up in the small city of Nankana Sahib in Punjab, Pakistan, once travel resumed.

I’m a third culture kid born to Pakistani parents, and while I may never have lived in my ‘passport country,’ I was determined to discover the Sikh side of Pakistan that I know nothing of. Repeatedly practicing how to pronounce the Sikh greeting of sat sri akal, I hit the road, taking a two-hour cab ride from Lahore to Guru Nanak’s birthplace: Gurdwara Janam Asthan.

I hadn’t even stepped foot onto the premises of the Gurdwara Janam Asthan before a pair of armed security officers demanded that I leave all my belongings behind—phone, wallet, and camera included. Now, even if I did decide to blindly trust this man’s demands, Pakistan isn’t exactly known for its law and order.

Visibly uneasy, I proceeded by a few steps as a stout, older officer called me over to the guardhouse. And like his peers outside, he insisted that I hand over everything. Everything. My hesitation persisted, which only seemed to anger him. “You think we can’t be trusted? Then take your fancy things and leave!” he yelled.

Still, I kept my cool—traveling solo across the world has taught me to stay collected in even the most unreasonable of encounters. A much calmer female guard nodded understandingly as I handed over my bag, explaining that I was visiting from abroad and knew literally no one in all of Punjab.

Empty-handed and questioning the safety of this situation, I started walking cautiously toward the gurdwara. But it wasn’t long until I spotted an administration building and veered right. “Continue straight!” yelled the officer in the distance as I awkwardly readjusted the massive shawl that I had wrapped around myself. Both men and women are supposed to cover their heads at gurdwaras worldwide out of respect to the Guru Granth Sahib, considered a ‘living guru’ and the holiest of all Sikh scriptures.

Approaching the white marble complex stripped of my travel essentials, I felt like I had failed myself. So, I started knocking on obscure doors, unsure of what I was hoping to find. That is until someone behind the third door opened it—and summoned me inside.

I was now in the control room of the world’s most significant Sikh temple, and the adrenaline rush was indescribable. While the room was cramped and the furniture was drab, I was mesmerized by the sheer number of CCTVs monitoring the goings-on in every inch of this gurdwara. “Can I help you?” asked a man who was clearly Muslim, recognizable by the zebiba (or prayer callus) on his forehead. That was my cue to reveal not only my desire to learn more about Sikhism but also the Sikh experience in Pakistan.

Singh unlocked a set of wooden doors just for me, introducing me to the sach khand, where the Guru Granth Sahib is placed to ‘rest’ each night.

It was obvious that the control room operator was having a slow day as he made a couple of calls. First, for a round of tea and cookies, then to the government official responsible for overlooking all seven gurdwaras of Nankana Sahib—Janam Asthan included. Young and spiffy, the manager soon showed up with an elderly, soft-spoken sevadar named Dyal Singh. There we sat—two gurdwara employees, one spiritual servant and me—making small talk in what can only be described as a mishmash of English, Urdu and Punjabi. The language barrier was undeniable, but the earnestness with which Singh spoke about his life as a Sikh in a Muslim country made my inability to speak Punjabi almost irrelevant.

Drawing parallels, he emphasized the importance placed on humanity in both Islam and Sikhism. He beamed as he revealed the VIP protocol provided to Sikh scholars by the Pakistani government. And he smiled as he reflected on the provisions made for the comfort of pilgrims at Gurpurab, an annual festival that hosts thousands of Sikhs from around the world, India included. Incidentally, the Pakistani province of Punjab is not only home to the birthplace of Guru Nanak, but also his burial site in the town of Kartarpur. In fact, the Kartarpur Corridor was created to offer a visa-free border crossing, connecting the Gurdwara Darbar Sahib near Lahore to Gurdwara Dera Baba Nanak in India, and accommodating up to 15,000 pilgrims a day.

Hearing his overwhelmingly positive narrative, I couldn’t help but confess that my experience had been far from ideal. But there was a reason. Turns out, a content-hungry TikToker had recently posted a video of herself bare-headed and dressed in “inappropriate clothing” at Kartarpur. The incident, for apparent reasons, spread like wildfire across media outlets in India, with Pakistani officials taking the brunt of the blame.

The aggression of the guards suddenly made a lot more sense. It’s no secret that countless influencers have been banned or deported over disrespectful behavior at sacred and historic sites worldwide. And here we were, paying the price.

Reassured that I was no such influencer, Singh not only had my belongings returned to me, but also invited me to tour the gurdwara with him. With our shoes off and hands washed, we started our afternoon together by sitting in silence at the sarovar, or sacred pool, where devotees perform a spiritual ablution known as isnaan. A scenic spot under an arched corridor reflected in the water, its beauty was marred only by the multitude of “No TikTok” signs around. Elsewhere, we stood solemnly under a tree with a tragic backstory; Singh explained that over 150 Sikhs were killed by Hindu Mahants (priests) during the 1921 Nankana Massacre, one of whom was hung on this very tree and burnt alive.

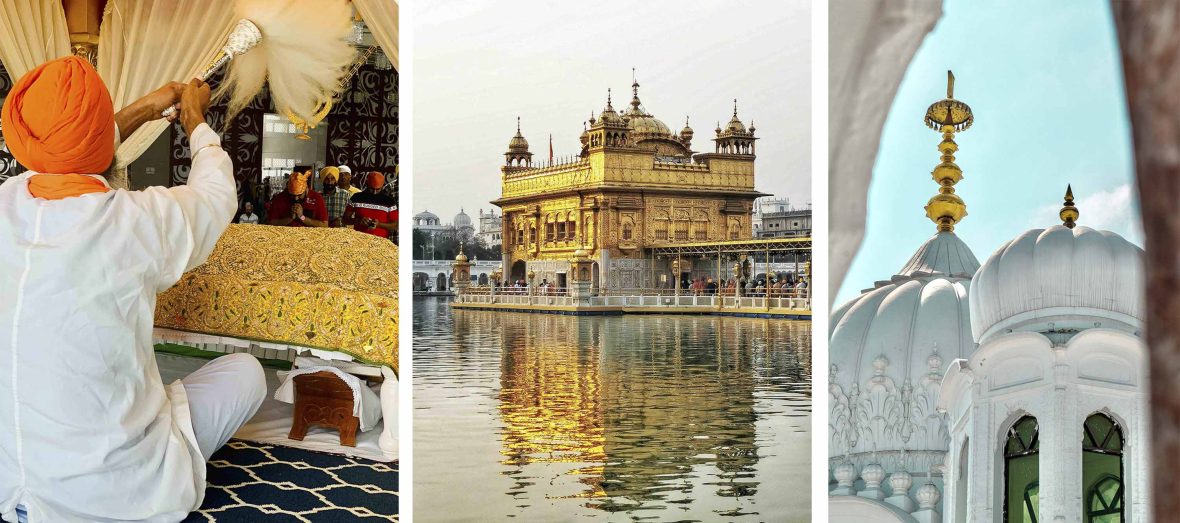

The education continued as we headed to a small room that contained the palki sahib, the main structure that houses the Guru Granth Sahib. Here, the holy scripture is placed on a raised platform under a domed structure and is continuously read aloud by a granthi, who is appointed only for its recitation.

Then, Singh unlocked a set of wooden doors, introducing me to the sach khand, where the Guru Granth Sahib is placed to ‘rest’ each night (complete with a bed and embellished cloth covering). We dined on a lunch of rice and chickpea curry, sitting side-by-side on the floor of Janam Asthan’s langar hall, a place that feeds the working class of Nankana Sahib on a daily basis.

After lunch, Singh said a little prayer for me under the storied tree at Gurdwara Tambu Sahib. Legend has it that as a little boy, Guru Nanak donated all the money given by his father for the purpose of trade, and therefore hid under the wild tree out of fear of being scolded.

Today, after witnessing the practice of seva as a way of life, I found myself touched by the goodness of the people I was with. But there are ways that I could have missed it. In retrospect, could I have accepted the rules of the guards, took a meaningless stroll around Janam Asthan and never seen Nankana Sahib through the eyes of Dyal Singh? Sure. Then again, no risk, no story.

Samia Qaiyum is a Dubai-based editor who specializes in travel and culture. She contributes to Elle Arabia, Vice Arabia, National Geographic Traveller, and Condé Nast Traveller. A textbook third culture kid with a perpetual thirst for adventure, she has lived in five countries and traveled to 34 others, racking up all sorts of weird and wonderful experiences along the way.

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: