An unexpected encounter with globe-trotting novelist and non-fiction writer Pico Iyer in his adopted home country of Japan leaves columnist Sarah Reid with plenty to ponder.

An unexpected encounter with globe-trotting novelist and non-fiction writer Pico Iyer in his adopted home country of Japan leaves columnist Sarah Reid with plenty to ponder.

Best known for his hyper-eloquent travel writing, there are few living writers quite like Pico Iyer, who published his 15th book, The Half-Known Life: Searching for Paradise, earlier this year. When I found myself on a day trip with the British-born, Californian-raised author in Hokkaido, I had to lean in—and scoop up a few nuggets of wisdom. This is what I learned on my bus ride with Pico Iyer.

It seems fitting that a Japanese proverb best sums up my impression of perhaps Japan’s most devoted tourist (Iyer has lived near Kyoto with his wife for 36 years, but not as an official resident), who, during our day out, keeps a low profile: Always observing, rarely questioning.

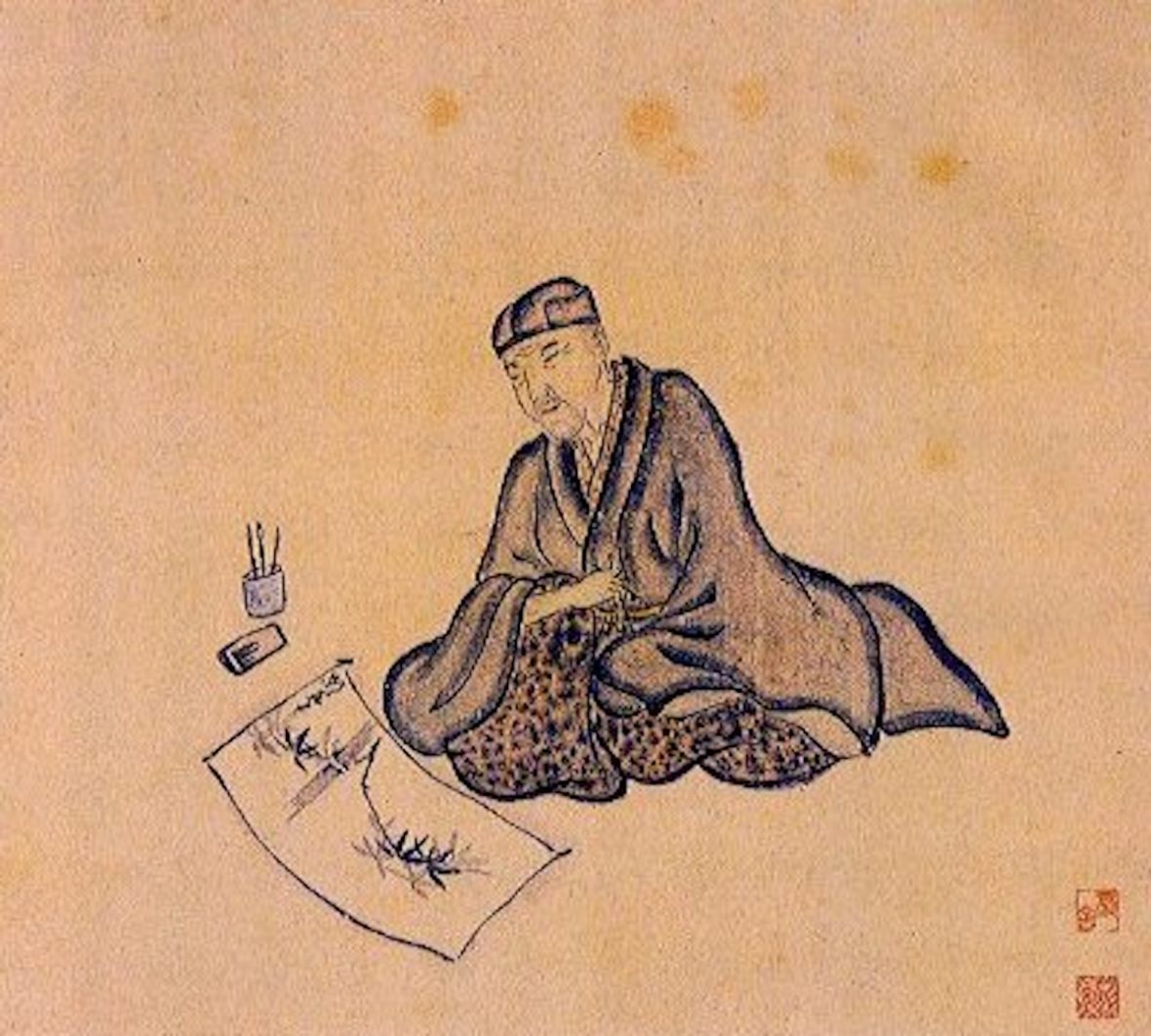

“He’s like a modern-day Bashō,” Los Angeles-based photographer Mark Edward Harris, who has collaborated with Iyer on several stories, including a North Korea feature for Vanity Fair, told me. “Haiku [which the Edo-period poet Matsuo Bashō is revered for bringing depth to] is all about observation, and Pico is the most thoughtful person I’ve ever met,” adds Harris. Indeed, Iyer reminds me that it’s hard to listen with your mouth open—without opening his own to tell me.

As a contributor to TIME magazine during the golden era of travel journalism (read: 1982), Iyer was constantly bouncing from one juicy assignment to the next. “I’d be sent off to Vietnam for a month to write a 6,000-word piece, then I’d go off to the next place,” he says wistfully.

In a deeply relatable quest to slow down, Iyer did a complete 180 in the early ‘90s and checked into a Benedictine monastery in California. His visit, and many since (“I try to go for a few days every season,” he says) not only informed much of his subsequent work, notably his 2014 book The Art of Stillness: Adventures in Going Nowhere, but also his approach to travel.

“I barely leave my neighborhood when I’m in Japan,” he says, admitting that in all his years in Japan, this is his first trip to Hokkaido. You only need to watch Iyer’s TED Talk on what ping pong can teach us about life (one of his four TED Talks with more than 11 million views combined) to discover that some of the most enriching cultural experiences can be found in our own backyard.

Living without a smartphone phone in 2023 is a pretty radical solution for finding calm in an increasingly fast-paced world, even for a semi-reclusive writer. But Iyer has never had a mobile phone of any kind. “People are always trying to get ahold of me, but they have to wait until I open my laptop to check my email,” he chuckles.

Iyer’s rejection of constant (digital) connection comes less from a place of technophobia (though he admits he still writes in longhand) and more from a desire to keep his inbuilt powers of observation, communication and initiative sharp—attributes that are easily forgotten when we’re glued to our devices.

There’s nothing like a rollicking travelogue to capture our imagination, inspire great adventures, and remind us that we can do hard things. But there’s a dwindling appetite for them, Iyer tells me glumly, with his latest book more likely to be found in the self-help aisle of a local bookshop.

Granted, it’s not difficult to understand why 21st-century readers have veered away from a genre traditionally dominated by white men with a penchant for exoticizing the places they visit. But in an era of travel bans and a climate crisis, the power of travel books to take us on thrilling journeys without leaving home feels more significant than ever.

From the page-turning expeditions of badass women travelers like Dervla Murphy and Cheryl Strayed to the beautifully detailed observations of Iyer himself as a man of color (his parents are Indian) exploring the world, many of the best travelogues are written from diverse perspectives, offering a rich dose of literary escapism that a standard travel article can never match.

Loosely translating to ‘harmony’ or ‘social unity,’ the Japanese concept of wa is at the heart of Japanese culture. And it’s perhaps the most useful souvenir we can take home from a trip to Japan, says Iyer. “Japan is a place where we can learn about harmony and community, and take the spirit of what we learned back into the world.”

***

Adventure.com strives to be a low-emissions publication, and we are working to reduce our carbon emissions where possible. Emissions generated by the movements of our staff and contributors are carbon offset through our parent company, Intrepid. You can visit our sustainability page and read our Contributor Impact Guidelines for more information. While we take our commitment to people and planet seriously, we acknowledge that we still have plenty of work to do, and we welcome all feedback and suggestions from our readers. You can contact us anytime at hello@adventure.com. Please allow up to one week for a response.

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: