A viable philosophy or government propaganda? Bhutan is often praised for measuring its worth by citizens’ happiness alongside its economy, but can a country really calculate happiness—and if so, how?

I’m meandering along the world’s friendliest road. Hand-painted boulders remind drivers to “peep peep, don’t sleep,” and, a few hundred meters later, “mountain of pleasure, if you drive with leisure.” And instead of saying ‘back off’, the bumper sticker of the truck in front of us politely reads: “Don’t kiss me.”

Bhutan is famously the only country in the world to rank Gyalyong Gakid Palzom, or Gross National Happiness (GNH), above GDP. Everything—from governance and economic development to cultural preservation and environmental conservation—is decided according to this holistic tenet, designed to measure and protect the collective happiness and wellbeing of the population. When the UN General Assembly passed the resolution in 2011, it praised Bhutan and urged other members to follow suit.

But how does a country measure happiness and what’s it like to live that philosophy?

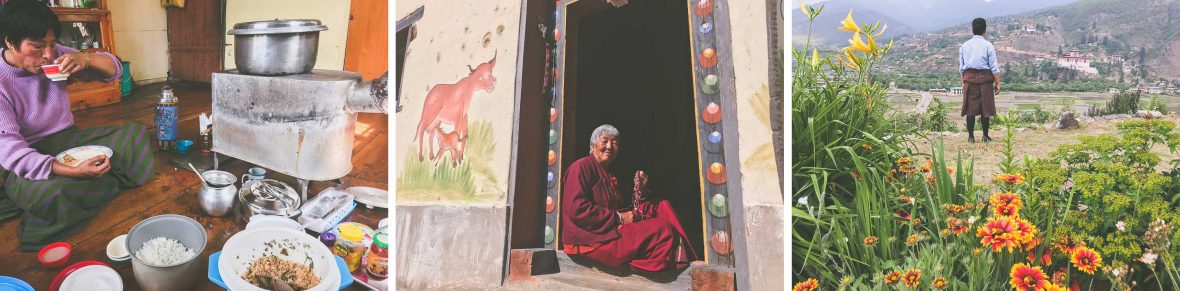

‘Gifted’ to the people by former King Jigme Singye Wangchuck in 2008, the philosophy, unique to the Land of the Thunder Dragon, is put into practice using a 30-page questionnaire that delves into the nine domains that are believed to contribute to a person’s happiness —psychological wellbeing, health, education, time use, cultural diversity and resilience, good governance, community vitality, ecological diversity, and resilience and living standards.

RELATED: Lagom: Is this the Swedish secret to happiness?

Participants are asked questions, such as: How often do you recite prayers or meditate? How satisfied are you with the relationship you have with your immediate family members? How many people close to you can you count on if sick, or if having financial problems? And how free do you feel to express your ideas and opinions?

The Bhutanese government argues the philosophy acts as ‘a compass towards a just and harmonious society’ and the questionnaire identifies gaps in happiness—such as that men tend to be happier than women, and urban, educated residents tend to be happier than rural citizens—and where they can improve amenities to re-address the balance. Ironically, though, Bhutan ranked 97 out of 156 on the 2018 World Happiness Report although they attribute this to the survey measuring happiness only via material wealth.

RELATED: Could travel really be the best medicine?

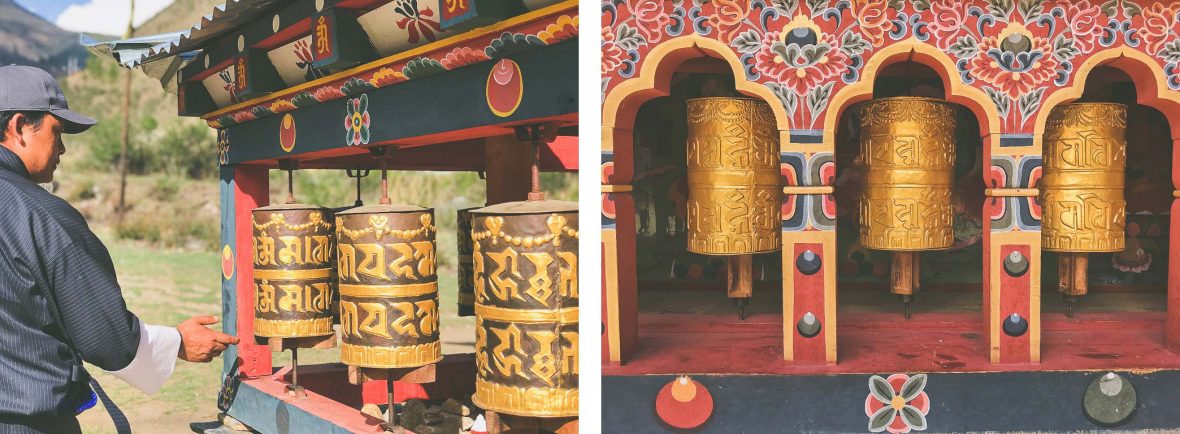

I ask my guide, Sonam Pelden, what he thinks as we join the thrum of locals circling like honeybees around the Memorial Stupa in Thimphu, built in 1974 in remembrance of Bhutan’s third king. The elder generation are dropped off by their kids with a packed lunch and spend the day here, spinning the prayer wheels and touching their prayer beads. “It becomes a community which makes them happy,” says Sonam.