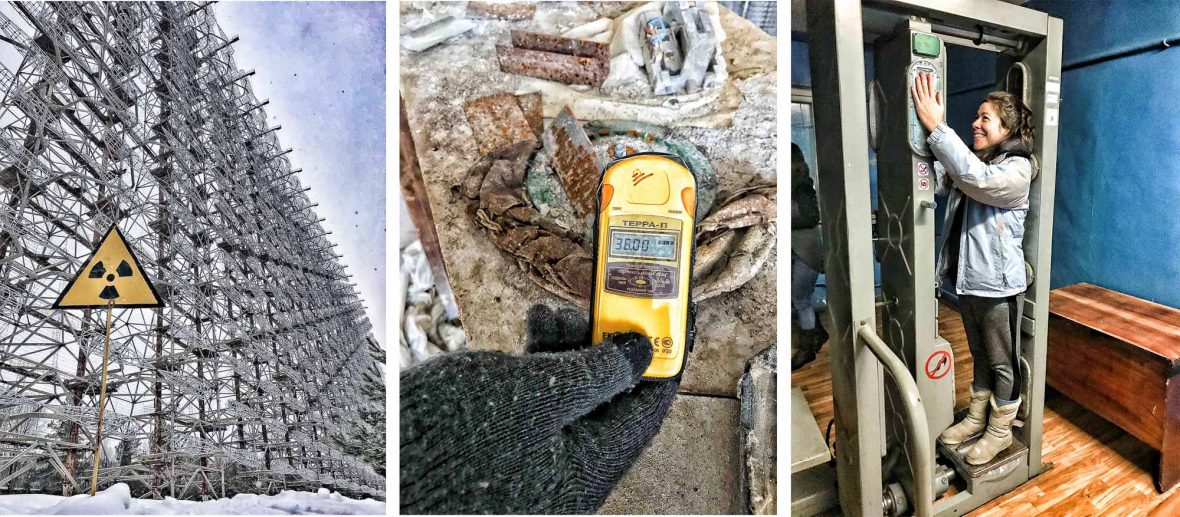

Thirty-two years after an accidental nuclear explosion reduced Chernobyl to rubble, Emma Thomson discovers the reality of life—and radiation—in this remote Ukrainian region as it begins to come alive again.

Ivan’s back is bowed as if the falling snow, gathering on his threadbare coat and Cossack fur hat, were leaden. He leans on his branch-whittled walking stick, trying to load splintered firewood onto a small sleigh. He’ll need it. Evening is falling and the mercury already reads -17° Celsius (1.4° Fahrenheit).

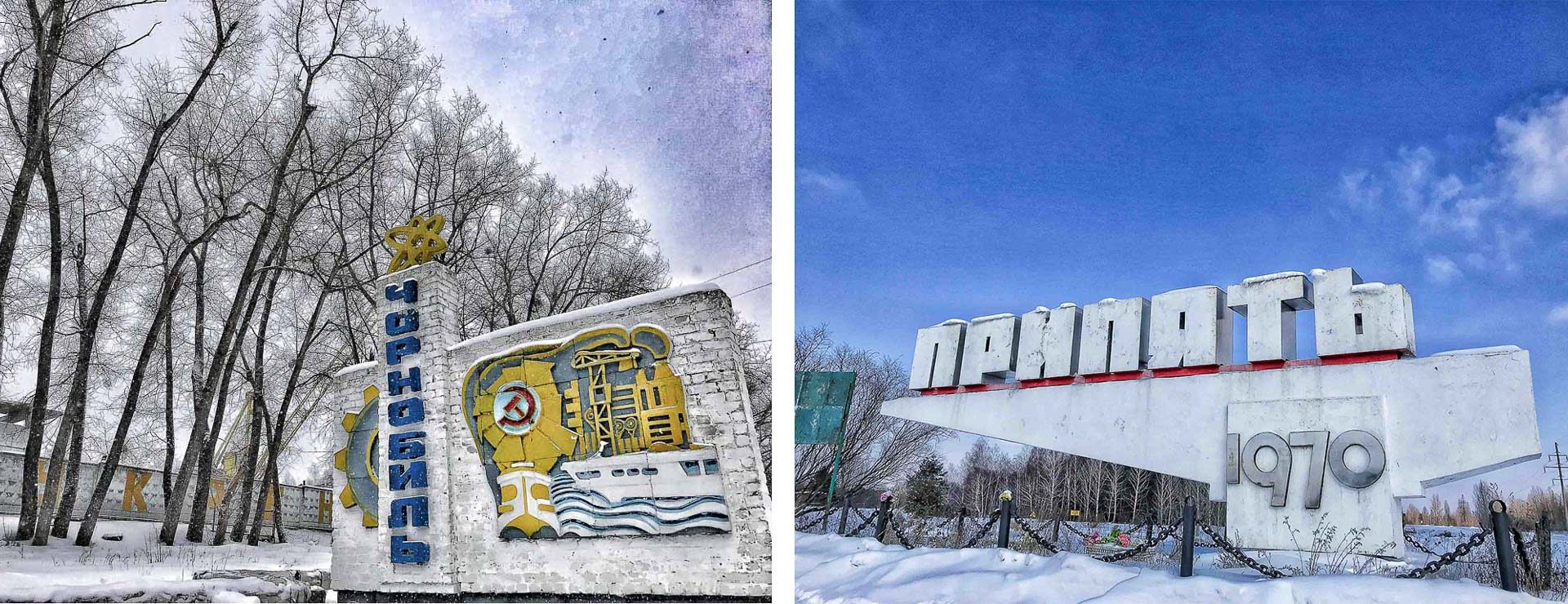

Eighty-two-year-old Ivan Semenyuk is a samosely, a self-settler; someone who chose to return to their village inside the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone after the 1986 explosion. The 18-mile radius was set up after reactor number four of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant overheated, surged out of control, and generated an explosion the equivalent of 500 nuclear bombs on April 26, 1986. Situated 120 kilometers (75 miles) north of the Ukrainian capital Kiev, it’s touted as one of the most polluted places on Earth.