There’s a lot we don’t know about life on Earth, and it’s disappearing in front of our eyes. Scientists are trying to document as many species as they can before they’re extinct, but how they’re doing it is the subject of debate.

There’s a lot we don’t know about life on Earth, and it’s disappearing in front of our eyes. Scientists are trying to document as many species as they can before they’re extinct, but how they’re doing it is the subject of debate.

If you had to guess, how many types of wasps do you think there are?

If you’re anything like us, you didn’t put the number in the hundreds of thousands. But the people who spend their lives studying exactly this say it’s at least that high. But exactly how many wasp species are out there, what they are, and how they behave is the source of ongoing research and discussion.

In a new feature published by Wired, Brooke Jarvis details the heated debate among entomologists (bug scientists) over how to identify new species and differentiate between existing ones. And while Jarvis’ writing makes the arcane fascinating all on its own, within the esoteric and obscure details is a story of urgent, global importance. In short, an academic disagreement over 403 new species of wasps is a microcosm of threatened biodiversity.

Knowing as much as we can about every species in an ecosystem isn’t just a project to satisfy scientific curiosity. Climate change is compromising habitats and disrupting the behaviors of most living things, and understanding what will happen and how to avert the worst loss requires as much information about all the interrelated species as possible.

Right now, there are roughly 2 million named species of all living organisms that exist in the animal kingdom, documented by just 500 experts throughout history. But that’s just a tiny fraction of what’s out there. In fact, it’s anywhere from a fifth to a thousandth of the total number, by scientists’ estimates. And there’s every reason to think that they’re going extinct faster than we’re learning that they exist, even with technological developments that could speed up the process.

Jarvis writes that for centuries, taxonomists would examine a potentially new-to-us species and compare it to images and physical descriptions of known species. If it was different enough, they’d give it a Latin name and note characteristics and a photo for the record. But the growing accessibility of DNA analysis offers a faster and more precise way to determine whether samples of potential new species are already known.

DNA sequencing, aka looking for differences in a particular snippet of DNA from the same section of each creature’s genetic code, is a contentious method among taxonomists. Some stand by the established practice of visual examination as more methodical, but the results with genetic technology are striking.

Michael Sharkey, an entomologist and taxonomist, used genetic technology to review an old project he had done identifying 100 new-to-science wasp species by the traditional method. As much as half of his work was wrong; he had either misidentified wasps of the same species as multiple different species, or designated multiple samples of different wasps as the same species.

Identifying species based on genetics isn’t a perfect or objective method, either. Two taxonomists examining the same specimens could (and have) gotten different results using different software and sections of DNA.

Earth is threatened by human actions. But that means that human action can solve the problem, too.

If you want to go into all the wonky details, Jarvis’ full article is a great read. But don’t let debates between taxonomists over methodology distract from the most important thing: Species are going extinct faster than we can learn about them.

There’s always been debate over where, exactly, to draw the line between one species and another. But the problem posed by development, urban sprawl, and a warming climate is much greater than that: species are disappearing before we even know they’re there. And when we zoom in on particular families within the biological kingdom, the sheer quantity of what we don’t know is even more concerning. The most-studied life forms, large animals, aren’t any more important than the overlooked and unknown insects, fungi, and microbes that are the underpinnings of healthy ecosystems.

As British hymenopterist Gavin Broad told Wired, “What do you know about the world if you’re only looking at a few species? You don’t know anything about it.”

You may have heard that we’re in the midst of the sixth mass extinction event in Earth’s history, but what does that mean exactly? The first image that springs to mind with the phrase “mass extinction” might be a meteorite hitting the Earth and killing all the dinosaurs. But scientists actually define it as a large loss of biodiversity in a relatively short period. And we’re talking “short period” from a planetary perspective, which can mean millennia as well as a single moment of impact. By that definition, we’re certainly in the midst of one now. In a 2021 study, paleobiologists projected that three-quarters of the species currently living on Earth will be gone within 300 years if things follow their current trajectory.

But by the same measure, the researchers emphasized, it’s still possible to prevent, slow down, or delay biodiversity loss before it reaches a mass-extinction level crisis point. Because unlike a meteorite on a collision course, life on Earth now is threatened by human actions. And that means that human action can solve the problem, too.

Climate change is a major culprit here, with changing standard conditions and increased variability of weather patterns. In a 2018 report, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change projected that six percent of insects, eight percent of plants, and four percent of vertebrates would lose at least half of their current range by the end of the century in the best-case (and unlikely) scenario of a 1.5 degrees C increase in average global temperatures. All told, another study estimated that one in six could face extinction if global temperatures continue to rise.

In the short term, though, habitat loss is just as big a threat. Given time, some species stand a chance of adapting or migrating to a changing climate, even when those shifts are happening as fast as they are now. But they’ll never get that chance if they don’t have anywhere to live. At least 1,700 species are predicted to become imperiled in the next 50 years if global land-use trends continue. And that’s only counting the species we know of.

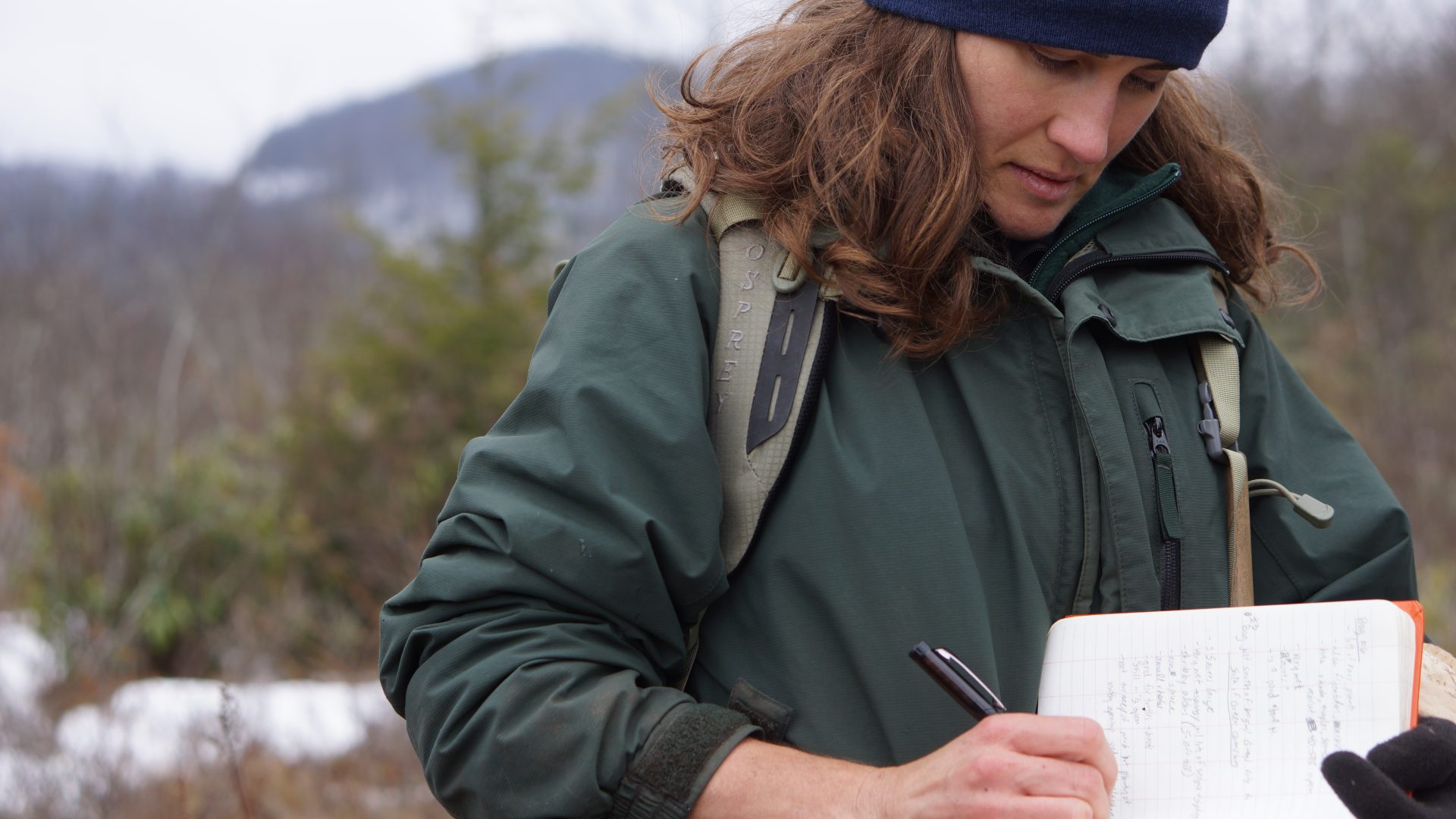

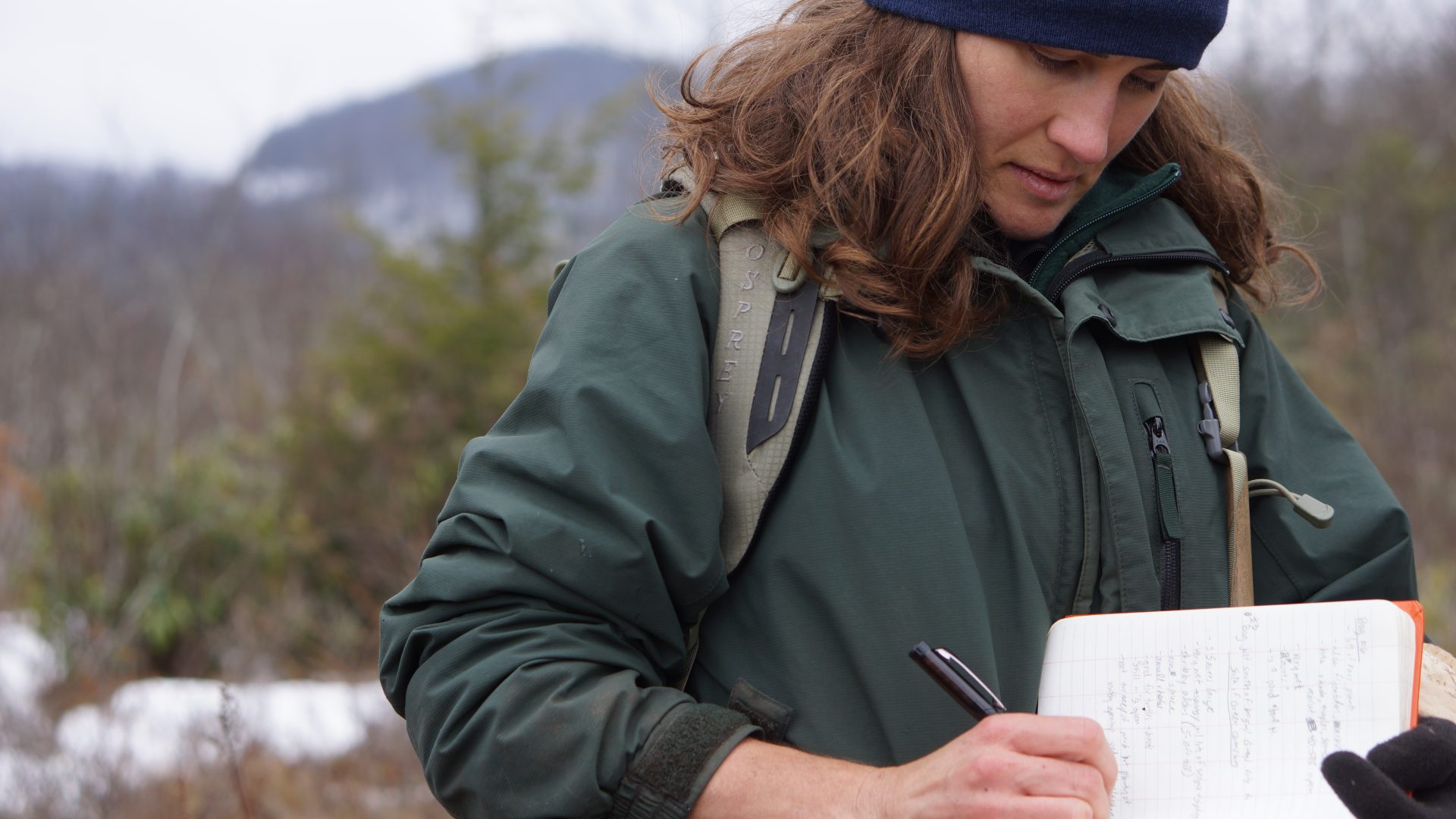

Miyo McGinn is Adventure.com's US National Parks Correspondent and a freelance writer, fact-checker, and editor with bylines in Outside, Grist, and High Country News. When she's not on the road in her campervan, you can find her skiing, hiking, and swimming in the mountains and ocean near her home in Seattle, Washington.

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: