In 2018, British Airways launched London–Islamabad flights for the first time in a decade, and travelers from 50 countries can now visit Pakistan without pre-arranged visas. Emma Thomson explores the changing face of a troubled nation.

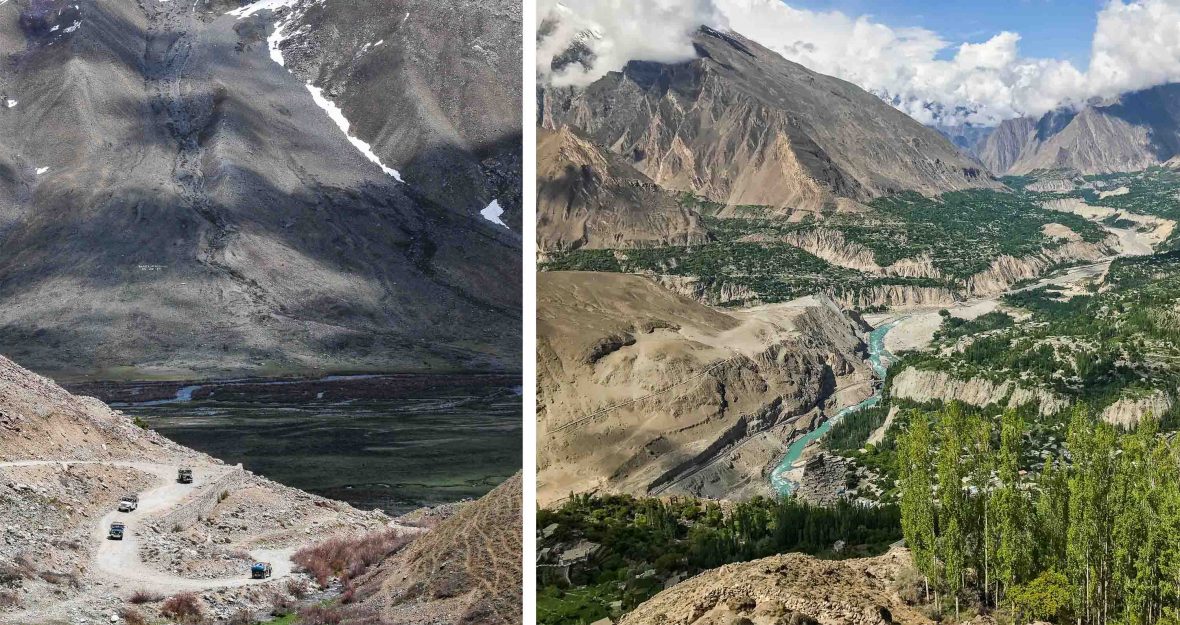

My head kisses the roof of the car with each bump in the road and dust coats me like a sugared croissant. But any discomfort is swallowed by the great yawn of the ancient Kaghan Valley.

The hour is late and the sinking sun casts the Kunhar River pewter and the far hills into a fading tier of purple silhouettes. Far below me, I spot a fisherman casting his line into the glacial waters.

It’s scenes like this that should entice travelers to northern Pakistan. Travel in the region isn’t always comfortable, but the rewards are as big as the panoramas.