In the mesmerizing mountains of Gilgit-Baltistan, a young adventure tour company is doing all it can to bring tourists back to Pakistan. Marco Ferrarese goes full-throttle.

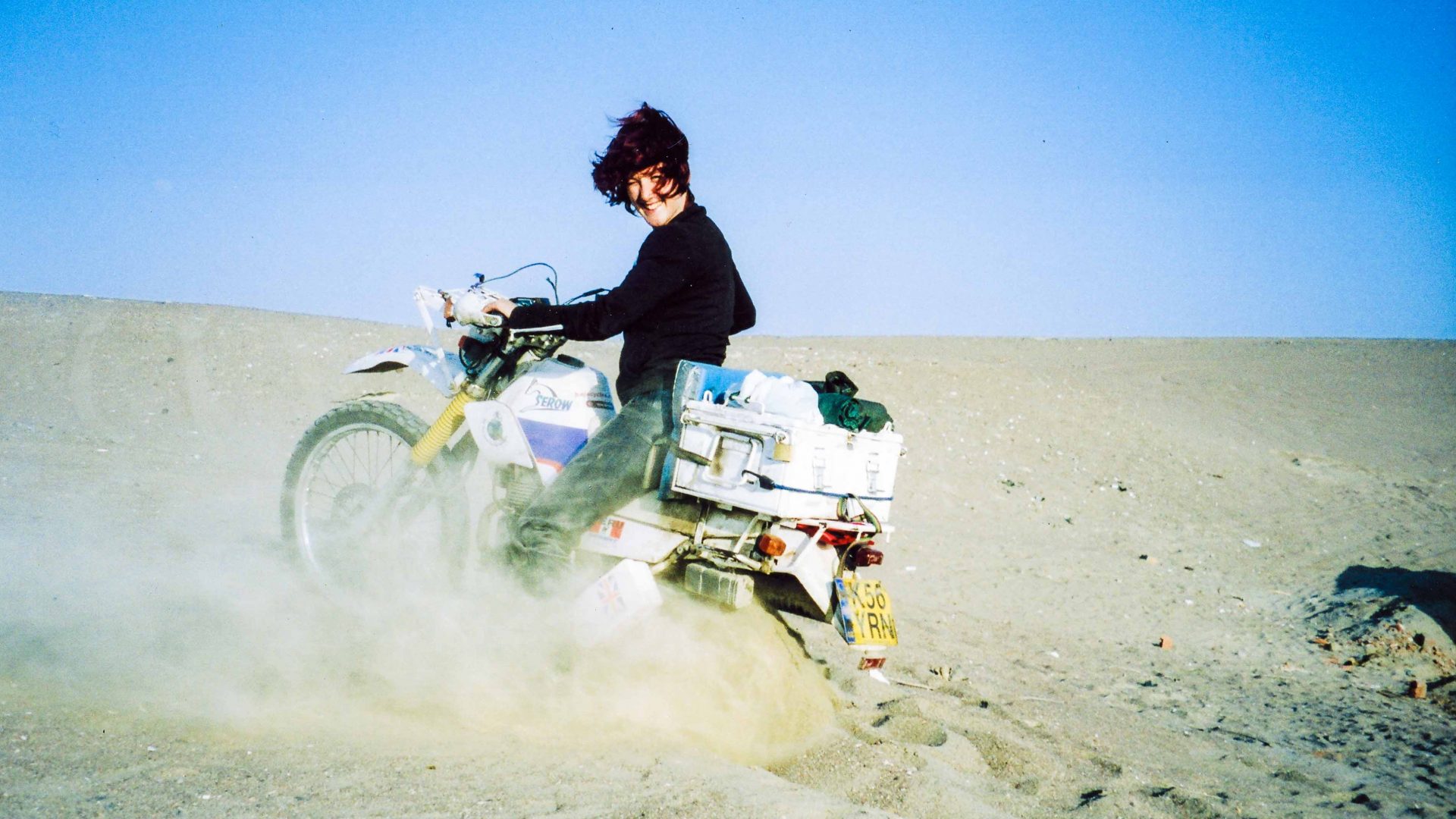

I’m riding a mean 150cc Suzuki along a barren strip of rocks and sand that most would never dare to call a ‘road’. And yet, in the mountains of Gilgit-Baltistan, this is the main 200-kilometer link between the legendary Karakoram Highway and Skardu, a lesser-known, but no less stunning, high-altitude desert valley.

As my wheels screech in the rubble, I squeeze to the right near the edge of a 20-meter drop. My wife, Kit Yeng, is sandwiched between my back and a couple of packs. Cold sweat rolls down my spine as I watch the Indus River run and crash between a majestic gorge of fang-like rocks that jut out below us.

Gulping, I look ahead and try to keep cool as I twist the throttle to overtake the pick-up truck that clogs my passage. It puffs exhaust fumes and dust into my face, choking me and blurring my vision. Its back is converted into rows of cages filled with chickens, half of them dead. Each time I get near the meat wagon, the pungent whiff of dying birds, old blood and fresh faeces slaps my nostrils.