How on earth do people make a living from exploring the world? And is it really as glamorous as it looks? Featured contributor Leon McCarron, long-distance walker, author and filmmaker, tells it as it really is.

Like many people, when I left university, I had no idea what I wanted to do with the rest of my life. I was self-aware enough to be grateful I’d had the opportunity to study, but faced with the prospect of the same temporary, unfulfilling jobs I’d held during those three years, I began to save—with purpose.

I wanted to do something that I could be proud of when I was old. I wanted to go on an adventure.

Finally, 14,000 miles after setting off, I arrived in Hong Kong, my savings spent, but my memory bank full. I’d grown in confidence, developed all sorts of resilience and grit I didn’t know I had, and seen enough of the world to know how much more there was to explore.

What was also surprising was discovering that I enjoyed sharing what I found—perhaps more than the travel itself. Initially, I kept a simple blog which had a readership of three (me, my mum, her friend.) That progressed to sending short stories to my local newspapers in Ireland—which had a similar readership to my blogs.

Then, a breakthrough: I got paid. The fee was nominal, for a story about trying to cycle through a Cambodian jungle and instead getting malaria, but it was a proof of concept.

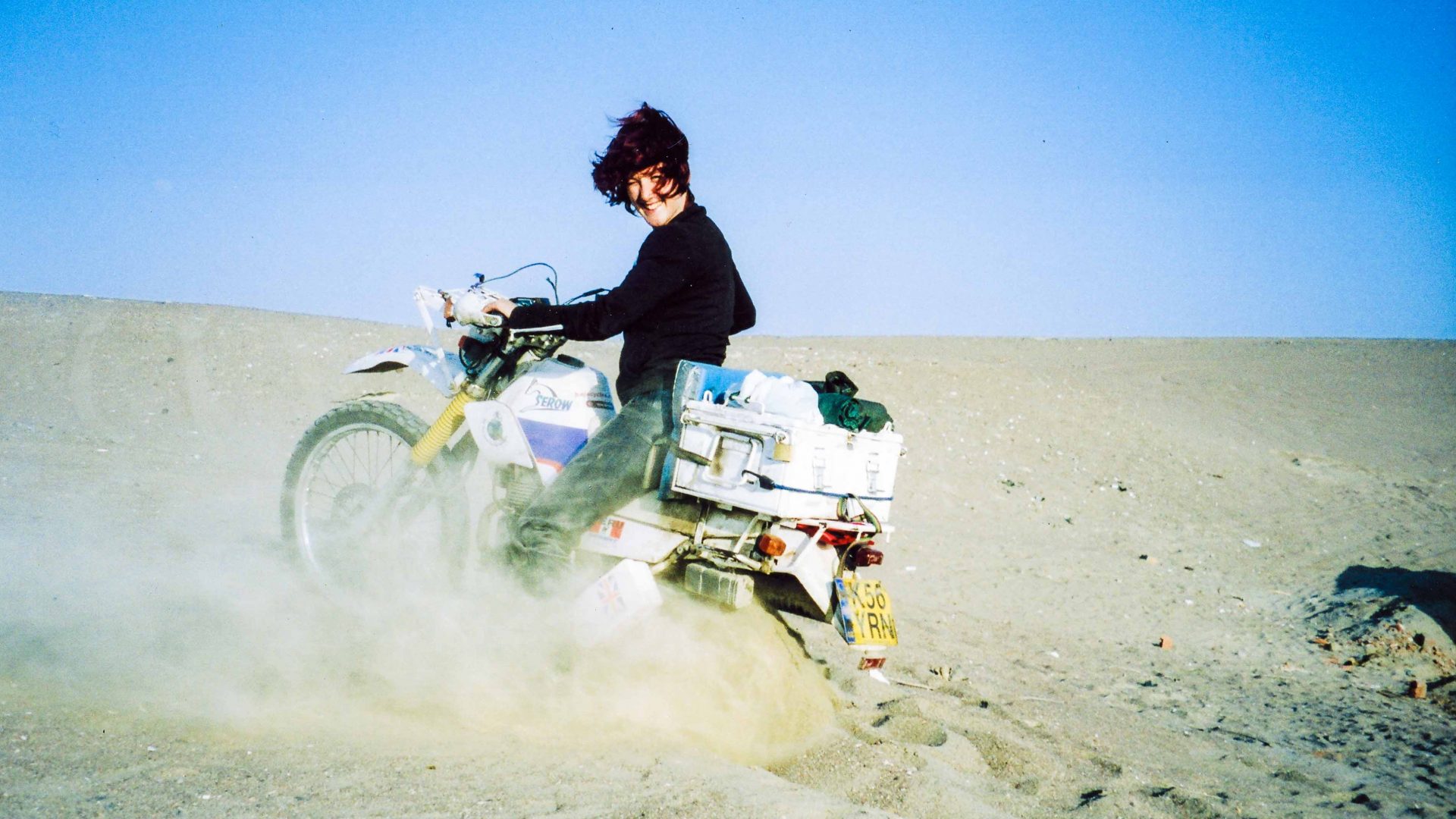

In between this busy schedule of bothering editors and headteachers, I’d go off on expeditions to find more things to talk and write about. I walked the length of China from Mongolia to Hong Kong (funding the trip by teaming up with someone—motivational speaker Rob Lilwall—who had much better contacts, experience and, being honest, funding, than I did) and I crossed the Empty Quarter desert in the Arabian Peninsula with adventurer and author Alastair Humphreys, who was not only generous enough to invite me to join him, but foolish enough to lend me the $1,000 that the trip would cost. (It took me over a year to save up enough to pay him back.)

RELATED: How to travel like a travel writer

Slowly, my expeditions became more professional, and the stories were collated in more savvy ways. I made films and wrote my first book, The Road Headed West, about cycling across North America. Encouraged by that, I’ve just published a second, The Land Beyond, which charts my 1000-mile walk through the Middle East.

2. Like anything, this way of life also requires an exceptional amount of hard work. It should become obvious over time which niche you’re suited to, and I’d encourage you to follow that—if you love writing, then write for all you’re worth. Make short films if you think you’re gifted with a camera. If you have an actual skill (like climbing, sailing or kayaking) then even better. Be innovative. Don’t just rehash the same journey that others have done before; give us something new. Keep your head down and do what you do—then keep doing it, better and better, until you get noticed. If you’re good enough, you will get noticed.

3. Finally—and the younger, idealistic version of myself would hate this—I’ve learned over the years to have some sort of a plan, and to put a price on what I create. A history of going on exciting adventures will give you the integrity when you begin charging for what you do. Of course, there are caveats.