Editor’s note: This article was published before the coronavirus pandemic, and may not reflect the current situation on the ground.

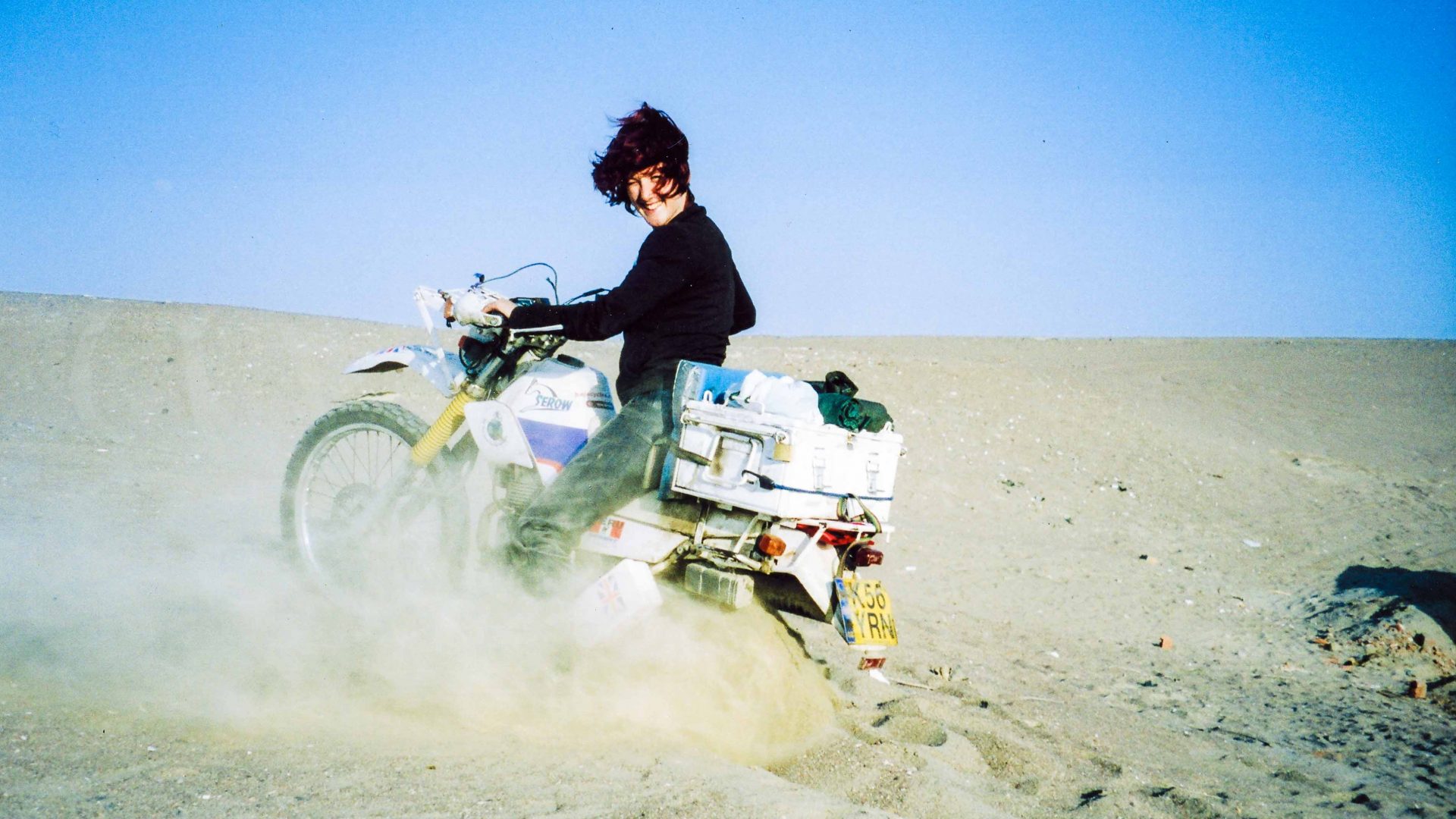

Challenging journeys and hard-to-reach places, often by motorbike, is what travel writer Antonia Bolingbroke-Kent does best. With her latest book highly commended for a prestigious award, we catch up with this fearless, multi-tasking, solo-traveling adventurer.

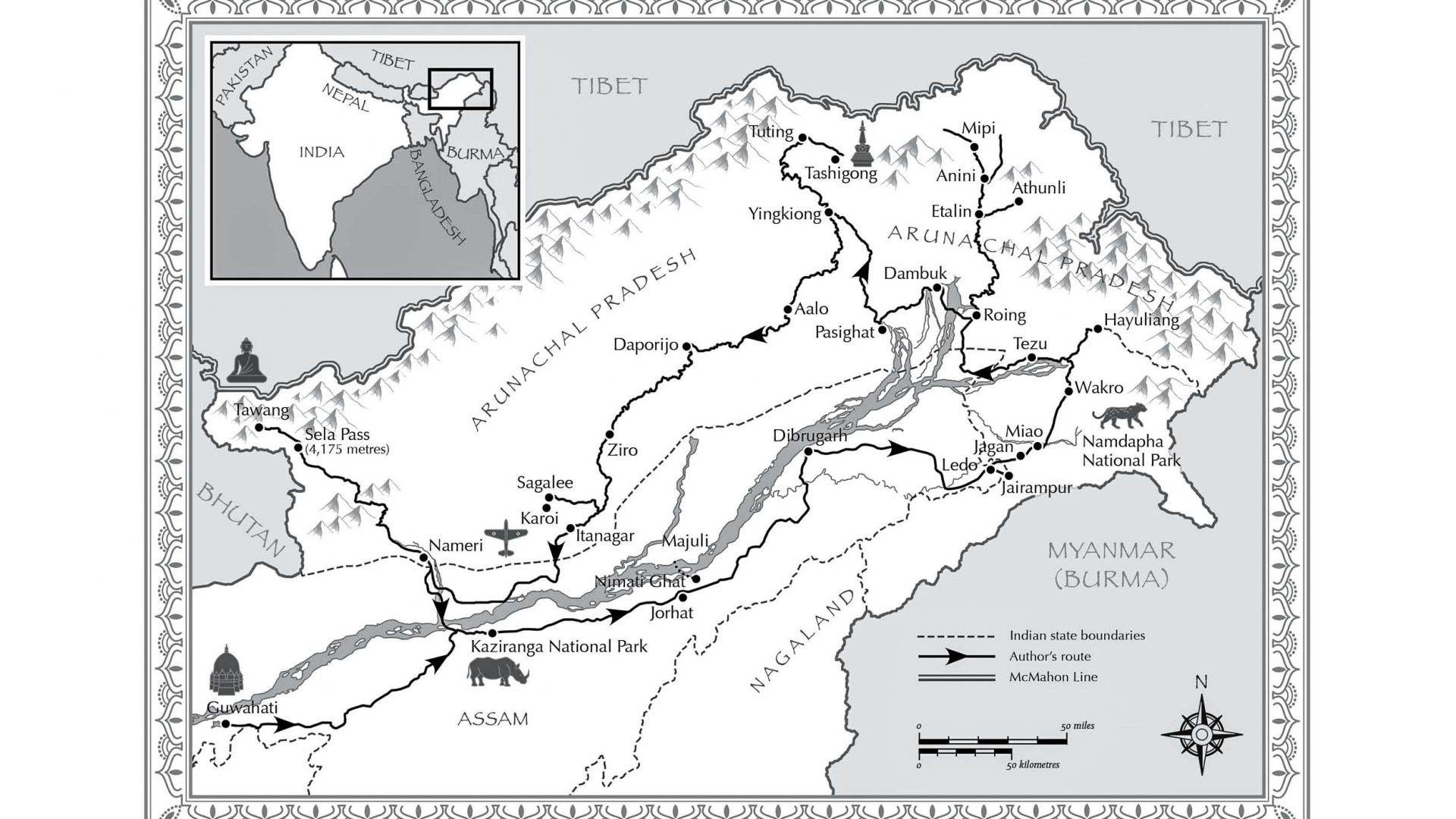

She’s a writer, public speaker, TV producer, and expedition leader—and her latest book, Land of the Dawn-lit Mountains, set in India’s far northeastern corner of Arunachal Pradesh, was highly commended for the 2018 Edward Stanford Wanderlust Adventure Travel Book of the Year.

This (still) under-visited region was closed to foreigners between 1950 and 1998 and even today, permits and restrictions make it a challenge to visit—but that’s all part of the appeal. We chat to Antonia about why she was attracted to this part of India, what makes it so different, and the enduring appeal of solo travel.