Back in 2013, ‘hiking through Afghanistan’ wasn’t high on the to-do lists of many travelers. But travel writer Tracey Croke set off for the country’s Wakhan Corridor anyway, determined not to let the headlines convince her otherwise.

I’m in Tajikistan with a man named Usef. The year is 2013.

Usef, it transpires, has a remarkably terrifying skill of zig-zagging his jeep at high speed to avoid potholes while turning his head a full 180 degrees to talk to me in the back seat.

“It’s a big drop,” I say, nodding at the unsurvivable rage of the Panj River, a hundred meters or so below. “Inshallah [God willing]” he smiles, rolling his eyes towards the heavens as if he has no influence over the matter.

In the distance, a bridge connecting high fences signals that my two-day drive through Tajikistan is coming to an end and the real journey is about to begin. We are lurching towards Ishkashim, the border crossing into Afghanistan.

The most common—and predictable—question people had asked me about traveling to Afghanistan was, “Why on earth do you want to go to a country like that?” And considering the majority of coverage that Afghanistan receives focuses on conflict, kidnappings, insurgency, the suppression of women and the opium trade, it’s hardly surprising. But sometimes it’s worth looking beyond the headlines.

RELATED: The motorcycle crew bringing tourism back to Pakistan

If you peruse a map of Afghanistan, you’ll notice a peculiar pointy piece of land which extends eastward between Tajikistan and Pakistan to the border of China. Long story short, this 185-mile-long strip of land—the Wakhan Corridor—was created as a buffer zone in the late 19th century to resolve British-Russian argy-bargy over Central Asian territory.

It was once a formidable section of the 4,000-mile Silk Road; one of the greatest trade routes in history. However, in 1963, the China-Afghan border closed and the Wakhan became a giant cul-de-sac.

The Wakhan is home to around 10,000 nomadic people of the Wakhi and Kyrghiz tribes. Yaks play a major role in the nomads’ survival, providing food and transport. Wool is turned into felt for lining yurts and dung is dried for fuel. The few traders who journey here barter supplies for livestock.

In recent years, a trickle of summer trekkers hiring yaks for support has provided some income but even so, living at the outer edges of human habitation is harsh. Life expectancy is low and infant mortality is among the world’s highest. But those who venture in will discover that one of the world’s most disadvantaged regions is abundantly rich in beauty, culture and the hospitality synonymous with Central Asia.

Even so, those all-pervasive headlines remained front of mind as soon as I left the ‘safety’ of Usef’s jeep, and a border official barely old enough to wield a razor blade began poking around my bag with his AK-47.

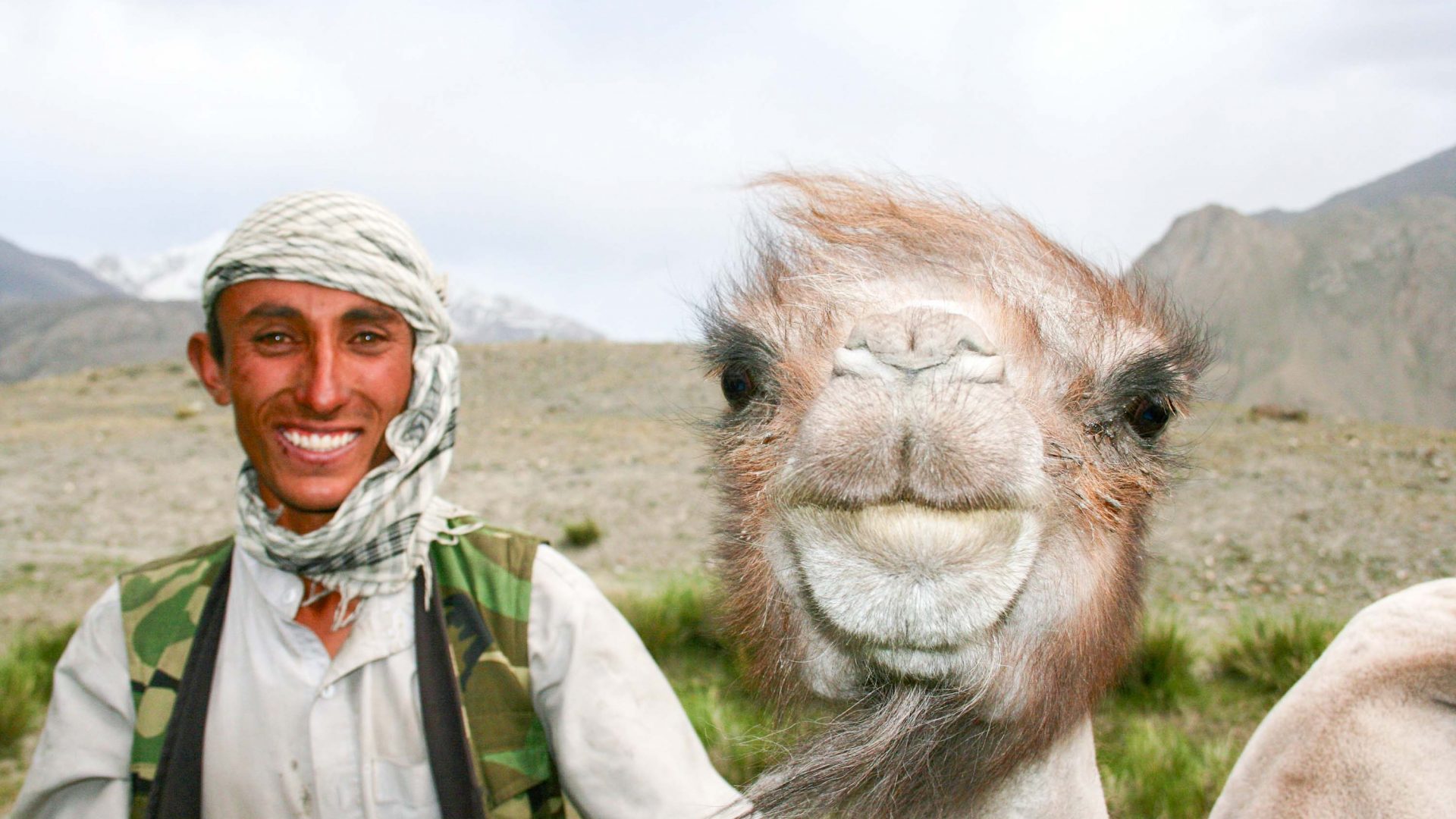

My cold sweats are instantly warmed by the galvanizing pride of my guide and Wakhi elder, Malang Darya, one of only two Afghans (at the time) to summit the 7,492-meter (24,580-feet) Noshaq mountain—the country’s highest peak.

“Welcome to my country!” Malang declares with arms outstretched. The warm welcome continues as we navigate Ishakshim Bazar, where we pick up last-minute supplies.

RELATED: My first war: The diary of a conflict reporter

“Salaam alaikum [peace be unto you]. It’s wonderful you’re here, have some chai,” insists one stall-holder. “Don’t worry, you’re safe. We don’t like the Taliban here,” assures another.

Countless cups of tea and several paperwork formalities later, we climb into rickety jeeps and set off into the Wakhan. It takes another day of picking our way over the rocky landscape to reach the start of the trek at Sarhad.

The varying microclimates of the region mean that one day we could be smelling wild thyme in the hot dry air and the next, we could be hiking blue-lipped against a blizzard. Terrain changes from mushy carpets of bright-green grass to ankle-bashing rock beds and high passes heaped with knee-deep virgin snow.

The endangered snow leopard evaded us but the ancient game of Buzkashi didn’t. In one settlement, we’re treated to this unparalleled display of cultural pride and horsemanship. It’s like a cross between polo and horseback rugby, where men wrangle over the headless carcass of a freshly slaughtered goat.

Over every ridge, a new vista surprises us. The unflappable, endearing yaks never fail to raise a smile as they saunter down into pastel valley. Faint figures herding goats in the distance are a sign we would soon be drinking chai, breaking bread and making friends again.

Was it worth the risk? Every bit. There is a cultural code of protection, community and friendship in the Wakhan that extends to those who travel there. I returned with a shifted mindset and the world has seemed a safer place to me ever since.

Five years on, in 2018, there is mixed news from Afghanistan. The Wakhan has deservedly been declared a national park. Malang featured as a guide to explorer Levison Wood in the hit series Walking The Himalayas. But sadly, the security threat in wider Afghanistan remains.

In the Wakhan though, it’s business as usual: Peaceful, spectacular and hospitable, still untouched by Manchester United shirts, the way it’s been for a thousand years. It’s the Afghanistan few people see. It’s the Afghanistan I’ll never forget.

—-