In search of purpose and a change of pace, freelance journalist Campbell MacDiarmid was drawn to conflict reporting. One year on, he recounts his time in Mosul, Iraq—his first war.

It all starts out like a grand adventure.

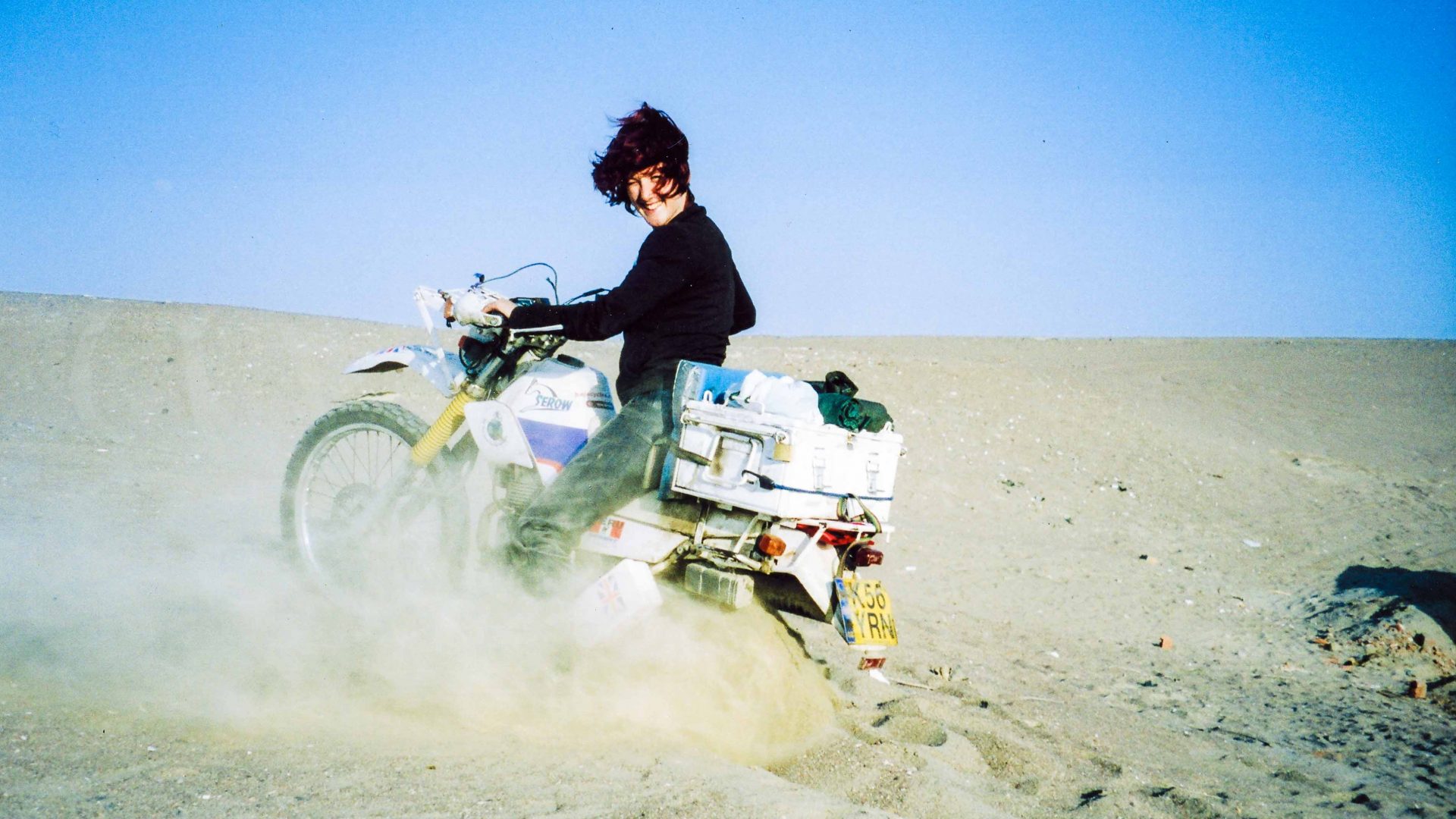

It’s the 17th of October, 2016. D-Day. I am in a column of vehicles descending in a cloud of dust down from the hills onto the Ninewa Plains. We are in the front of an attack by Kurdish Peshmerga fighters, who’ve been sent to liberate a series of Islamic State-held villages on the edge of Mosul.

Mosul. I’ve spent nights on sand-bagged hilltop positions gazing down at its twinkling lights. Marveling that over a million people down there are going about their business, all under Islamic State control. They’ve held the city, Iraq’s second largest, since June 2014. Since then, the jihadist group has shocked, appalled, and titillated a global audience by their draconian rule—and their relish for sophisticated snuff films.