How does a solitary, sea-locked existence change your perspective on life? French photographer Clément Chapillon explores in his latest book, Les Rochers Fauve.

How does a solitary, sea-locked existence change your perspective on life? French photographer Clément Chapillon explores in his latest book, Les Rochers Fauve.

Photographer Clément Chapillon arrived on the distant Greek island of Amorgos—the easternmost in the Cyclades—almost 20 years ago. Listening to his father recount travel stories from decades exploring the Aegean Sea, he eventually set out as a teenager to experience it for himself.

Despite Clément traveling extensively throughout the region, he instantly knew something was different when he stepped onto Amorgos for the first time. “Everything I was looking for on the other islands, I found it on Amorgos,” says Clément, who became fascinated by its local traditions and quiet isolation.

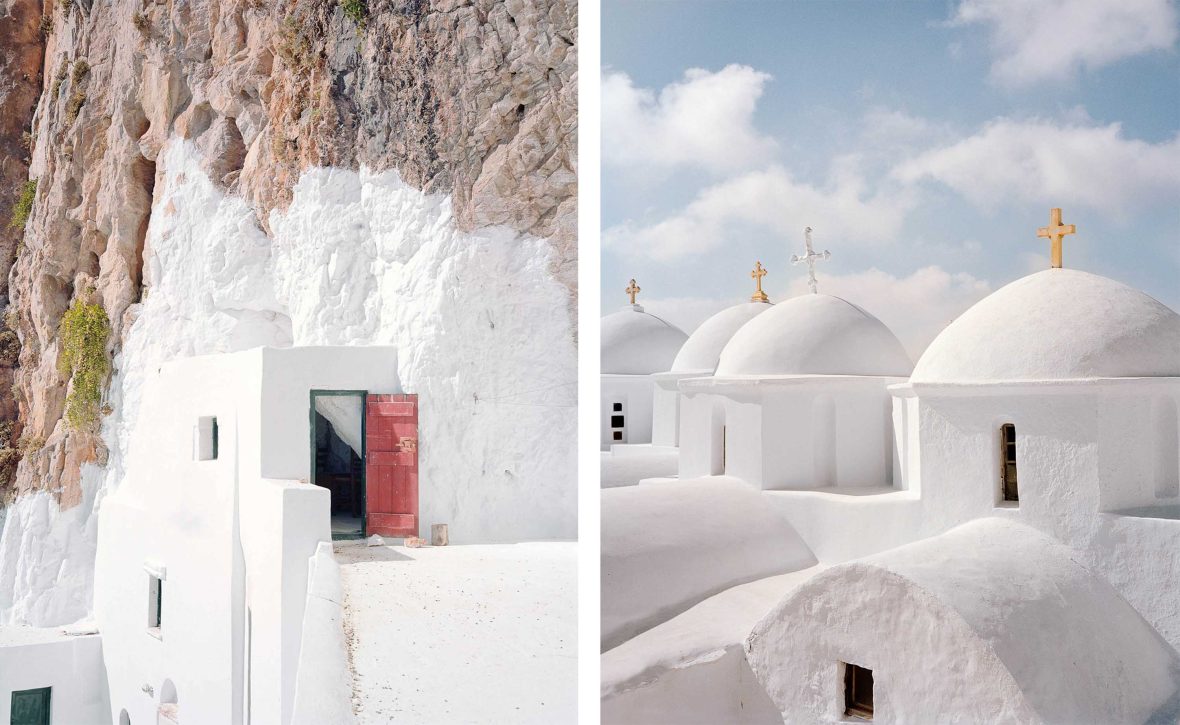

Returning almost every year since, Clément explains how life on Amorgos rests somewhere between reality and imagination. While the island’s scenic beauty is undeniable, the boundless seascape and daily monotony create an uneasy tension. Shot on medium-format film, he echoes this contrast and its effect on people in his latest photo book, Les rochers fauve.

“You realize that nothing much changes; that you’re just a small piece of dust in this endless cycle of life,” describes Clément. “It can be good in some ways because you feel a stronger connection to people, animals and gods. But there’s a dark side where you feel insignificant and completely trapped.”

Time slows down on Amorgos, at least for those accustomed to a city-bound existence. There’s little external influence on the island, with life revolving around communal customs and religion. Clément explains how many locals still follow the Olympian Gods, while several Cycladic-style churches like the 11th-century Monastery of Hozoviotissa adorn the craggy cliffs.

Across five trips to Amorgos for his series, Clément spent his time getting to know a handful of its 1,500 permanent residents… and the grip the island had over them.

“Religion is extremely important—more important than even mainland Greece,” says Clément. “All the rituals and traditions become essential because you need more connection to those around you to get through life.”

Amorgos is also home to three millennia-old acropoleis, but their significance is largely lost to time. In fact, few historical descriptions of the island exist at all. One that survives is an 1892 travelogue by archaeologist and writer Gaston Deschamps, whose conflicted thoughts on Amorgos’s splendor and insularity inspired Les rochers fauve and its book design.

“I had exactly the same feeling he described 150 years ago; the way the island feels, its geography, the wind, the animals that roam everywhere. But at the same time, he writes about this paradise like you are stuck,” says Clément.

Across five trips to Amorgos for his series, Clément spent his time getting to know a handful of its 1,500 permanent residents. In particular, he wanted to meet the foreigners who started new lives in this isolated place. With some arriving decades ago but never leaving, he was driven to understand what grip the island had over them.

Clément became close with Carolina, an elderly author who had settled on the island over 50 years ago. Living in an abandoned village called Langatha, opposite a sacred valley said to contain mythological fairies, she taught many of the island’s native-born residents how to read and write English. She told Clément that Amorgos was exactly where she needed to be.

“I was touched by this old lady, but she died during my last visit when I was there to show her the portrait I had made of her,” says Clément. “I still see her face when I think of the island as if she had become part of the landscape.”

Jerry was another island character Clément got to know. Having stumbled into him early one morning, he learned how this former submariner had traveled the world yet still returned to settle on Amorgos. Followed by a troupe of goats, dogs, donkeys and horses across the island, Jerry’s role as an ad-hoc shepherd suited his preference for solitude.

For Clément, life on a lonesome island—even one so beautiful—means “confronting your own presence.”

“I have a picture of him with a goat in his arms,” says Clément. “He gives them a name; he speaks with them, and they even smoke cigarettes together. He needs a relationship with someone, but he only lives with the animals.”

Over time, Clément realized that many people on Amorgos simply want an existence unburdened by the outside world. Although some consider the seemingly eternal sea surrounding the island an unwelcome reminder of their isolation, others view it as a faithful bulwark for their secluded lives.

The series title, translated to “The Tawny Rocks” in English, is taken from Deschamp’s musings and encapsulates this duality. The original French is a homonym that describes the landscape’s enchanting pink and brown hue, but also the perception of a wild beast. For Clément, life on a lonesome island—even one so beautiful—means “confronting your own presence.”

“You know, the word isolated has a Latin root meaning ‘island’. I wanted to see how this existence changes people,” says Clément. “In a city or even just the mainland, you can take your car and see other things. Here, you have the sea, the mountains and the wind.”

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: