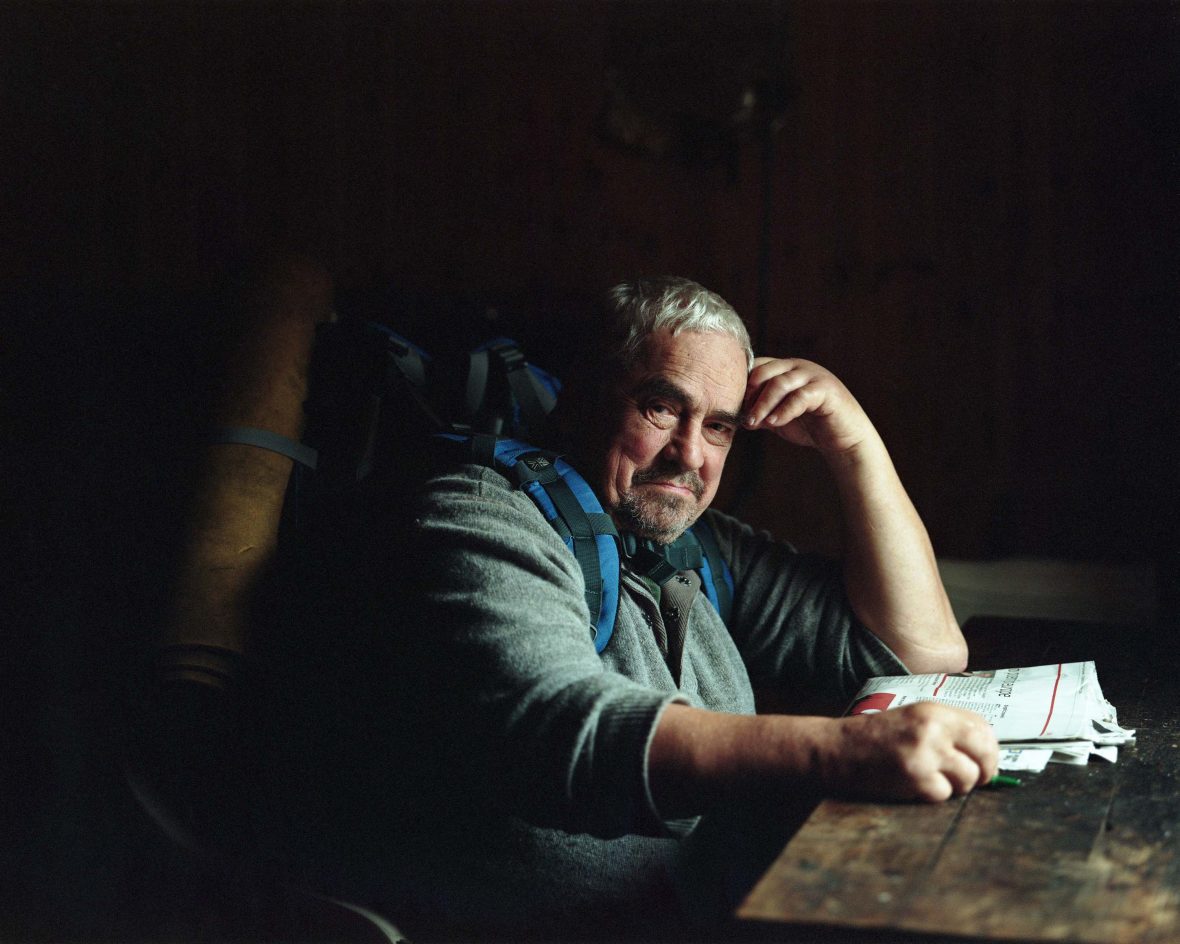

High in the hills across Great Britain, bothies serve as shelter for hikers, ramblers and wayfarers alike. But they’re so much more than just somewhere to lay your head, as photographer Nicholas JR White discovers.

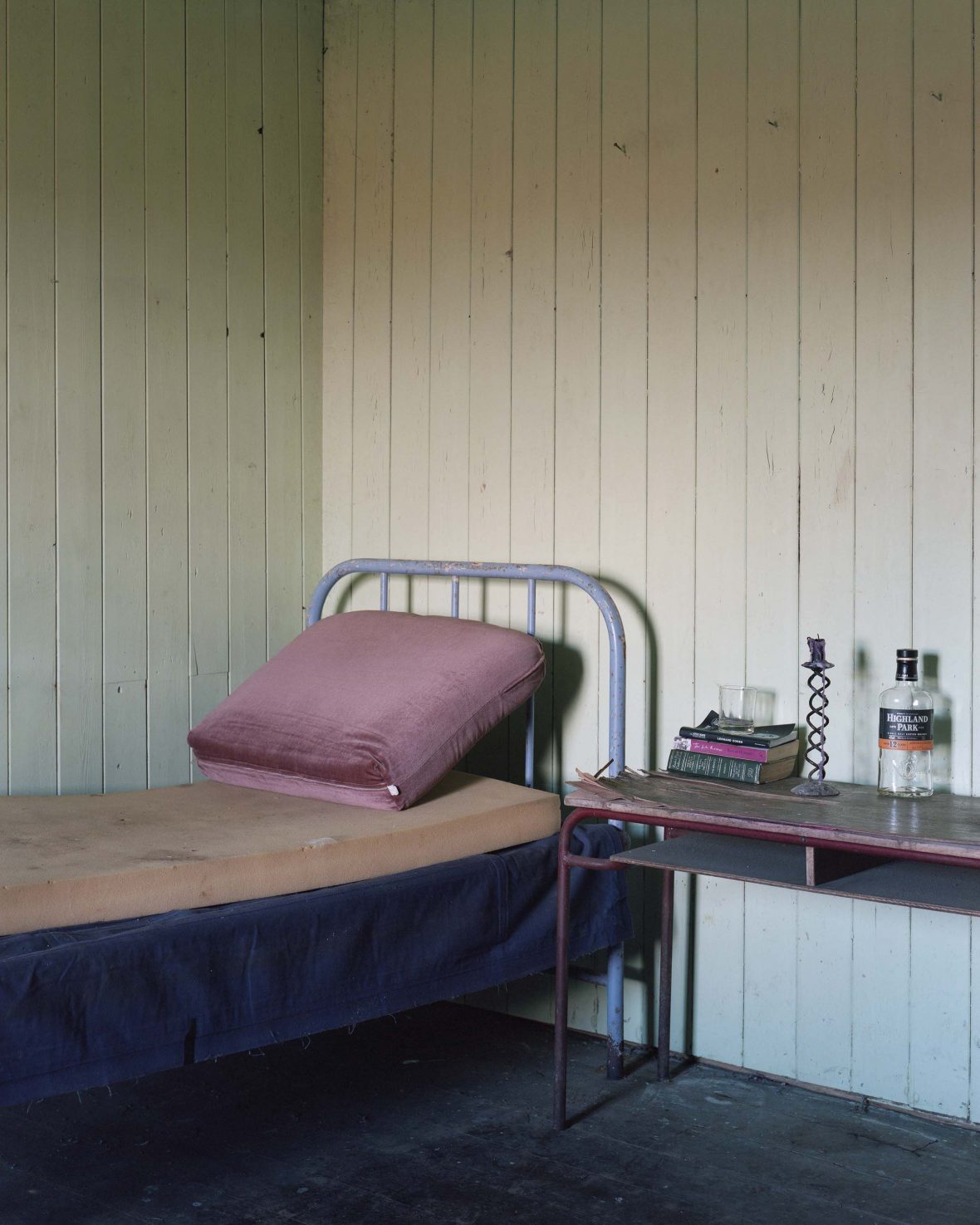

Cobwebs glisten in the corner of the room as the sun bursts its way through the small window. Makeshift clotheslines zig-zag from wall to wall, adorned with clothing from the previous day’s hike. Hundreds of inscriptions are scratched into the metal ceiling, telling a vivid story of the people who’ve laid here before me. Powerful gusts charge down the valley whipping the walls with spindrift and forcing the wooden door to rattle on its hinges.

Jumping down from my sleeping platform and onto the cold hard floor, I slip into my boots, unbolt the door and step outside. The frozen ground squeaks and cracks as I walk, and the call of ptarmigans echo around the mountains.