They

bring color to the streets of Dhaka, but as populations rise and cities

modernize, Bangladesh’s rickshaws, and the traditional art that adorns them,

are at risk.

On one of Old Town Dhaka’s narrow lanes, two men toil

away in a cycle rickshaw workshop. One at a treadle sewing machine stitching plastic

appliqué panels, the other painting metal wheel rims. Beside them is a new rickshaw,

decorated with hot-pink illustrations of three film stars, a festooned hood,

metal stud detailing and handlebar streamers.

Outside, Yousuf, a rickshaw artist, unfurls a fabric

scroll revealing an illustration like the one on the new rickshaw. “This is one

of the most popular rickshaw paintings in Dhaka,” he says. The piece isn’t

destined for a rickshaw though; it was a tourist commission.

Creating art for visitors has become a new income stream—because

these days there isn’t enough rickshaw painting work to sustain Yousuf and his

family. “There are still a few other artists working here in Old Dhaka. Probably

around 12 of us.”

From Dhaka, I pick up the rickshaw trail on the muggy streets of Rajshahi, an industrial city near the western border with India. The tinkling sounds of rickshaw bells fill the air and idyllic pastoral scenes dominate the rickshaw back-plates.

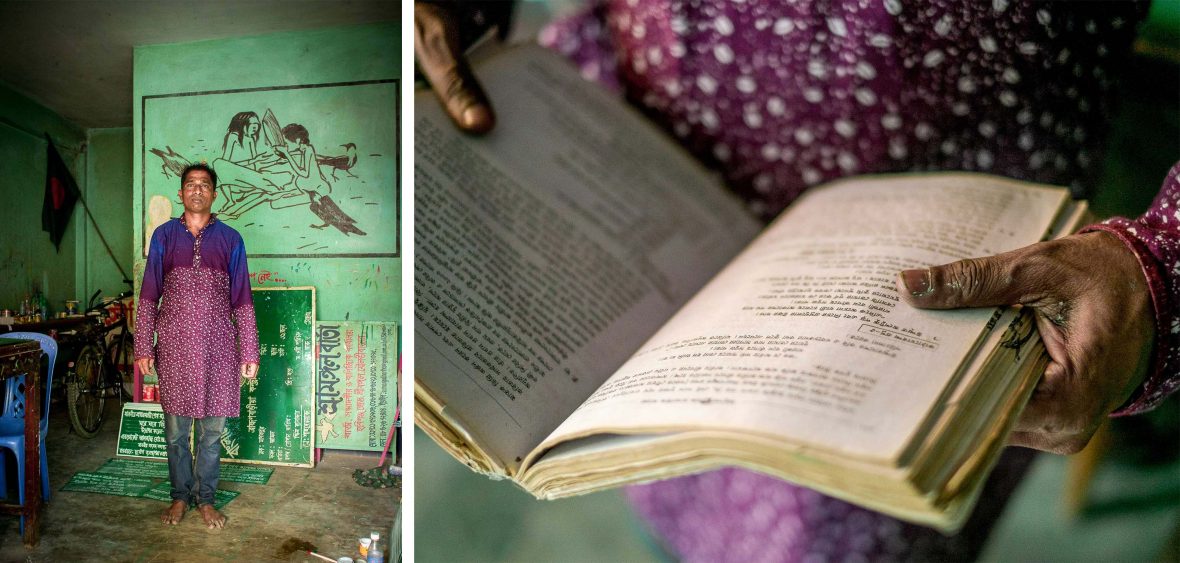

I track down a local rickshaw artist, but I’m too late. “I stopped painting about 10 years ago,” he tells me. He explains that he runs the family rickshaw repair garage now. A mural of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Bangladesh’s omnipresent founding father, painted on the workshop wall in front of us confirms he’s a talented artist.

RELATED: Forget Uber Eats: Mumbai’s 125-year-old food delivery system wins the day

“I couldn’t compete with the price of digitally produced art, and the local government stopped issuing rickshaw permits, so there aren’t enough rickshaws to paint.”

It’s not as simple as keeping with tradition. Traffic congestion is a problem across Bangladesh—getting from one side of Dhaka to the other can take hours and for the government, rickshaws are a symbol of underdevelopment and the scourge of congestion in the country’s crowded cities. And yet, with one in four Bangladeshis living in poverty, rickshaws remain an essential and affordable mode of transport.

My next stop, Chittagong on the southeast coast, is home to Bangladesh’s biggest port, and where the traffic is as bad as Dhaka’s. A tip from a local friend leads me to a covered arcade of shops, humming with the sound of sewing machines. Inside, a middle-aged man in a lunghi (sarong) and short-sleeved shirt sits on a wooden stool, painting lily-flower designs onto a rickshaw panel.

Bonjo trained as a rickshaw artist in 1969 and has had his own workshop for 35 years. Three students trained under him, but none work as rickshaw artists any more, “There’s not enough work for them now. A few artists I know left Bangladesh to work in the Middle East,” he says.

Would he go?

“No, I’m too old,” he smiles. “I’ll stay, even though there’s less work.”

When work does come in, Bonjo works around the clock, alongside his son, who is not an artist. The pair is finishing a bulk job of 10 new rickshaws, which they’re painting with simple water-lily motifs, the national flower of Bangladesh.

Companies sell digitally mass-produced artwork at half the price artists charge—so artists have to ‘adapt or die’. At least, hand-painted signs are still popular in Bangladesh and for Bulbul, that’s proved a more profitable way to use his skills.

Back in Old Dhaka, where this colorful odyssey began, I meet Yousuf again. The narrow, leafy courtyard of his apartment, where neighbors chat and children play, is also his home studio while the corner opposite his front door serves as his compact workspace. An easel, paints, brushes and canvases are organized on a wooden platform at which Yousuf sits cross-legged.

“My father was an artist and I learned how to paint from him,” he tells me. “My six brothers are all artists too.” Yousuf’s father is a renowned first-generation artist called Golam Nabi.

Acceptance and adapting seem to be key to survival here for Bangladesh’s talented rickshaw artists. While Yousuf’s first love is painting rickshaws, he also enjoys painting vibrant wildlife scenes and depictions of idyllic village life. “The artwork for tourists is more varied than the work I create for the rickshaws,” he says. It’s also more sophisticated and detailed than the work I’ve seen on the rickshaws, I note.

With the push to remove rickshaws from the roads and the rise in mass production and digitization, it’s hard to know how much longer Yousuf and those like him will be able to continue their work.

Still, Yousuf himself is hoping to pass down his skills. In fact, his young daughter, Asha, is sat beside him, watching her father paint and playing with his brushes. “She seems interested in learning to paint,” he says, looking down at her—with something that looks a lot like pride.