In another concession to market forces, both international and domestic, Bagru’s chhipas are increasingly substituting Rajasthan’s natural earthy-hued dyes for chemical pigments that produce brighter colors in every shade under the rainbow. These pigments are often cheaper, but Jeremy believes there’s an environmental benefit to using them too.

“The biggest issue in Bagru is water scarcity,” he says. “In order to use natural inks a fabric often has to be washed four to five times [and boiled] before it’s finished, whereas with a pigment print, the fabric just has to be washed once.” Rajasthan is classified by the World Resources Institute as extremely water-stressed and Bagru no longer has a natural water source; the village’s river ran dry in the 1980s and these days, the water comes from an underground bore hole or is brought into the village by water tankers.

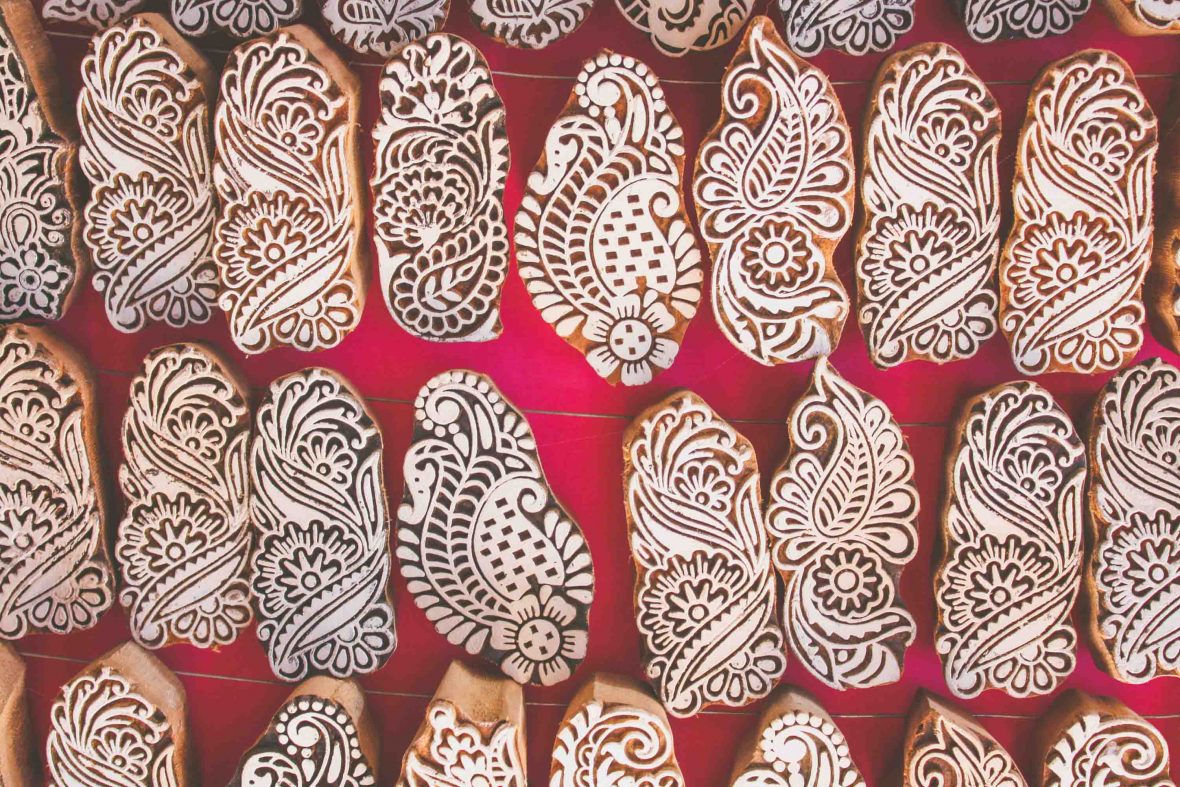

The Wabisabi Project is one Bagru workshop bucking the trend, working exclusively with natural inks and dyes derived from plants, roots, barks, seeds and flowers harvested in Rajasthan. The Jaipur couple that runs it, Avinash and Kriti, were not born into a chhipa community yet they are driven by a fascination with, and desire to preserve, the traditional motifs, dying recipes and artisanal manufacturing lore of the region.