On the shores of Indonesia’s third largest lake, a travel writer and photographer find out that a little dancing can go a very long way with the local indigenous people.

“C’mon, try it again: One and two and three and four, one and two and three and four, right foot, left foot.” Annie, an Indonesian woman I met about an hour ago, is holding and shaking my left hand, coaxing me to line dance on a moonlit street corner.

“OK, I’m following,” I reassure her, shouting over the barrage of techno beats that fills the night. But no matter how hard I try, I just can’t move like the circle of happy people around me.

“C’mon Marco, concentrate!” Annie hisses, her tone slowly slipping into annoyance. She’s already showed me the dance steps several times. The pounding of the feet: Two times to the right and two times to the left. It sounds simple, but it isn’t. I’m confused. And I feel like an ass.

I glance up and see that my wife, Kit, has already mastered the communal dance, and is seamlessly blending in with the locals. Meanwhile, I’m a mess. The old man holding my right hand turns his head sideways and laughs openly in my face.

RELATED: No Tinder in the desert: How Chad’s Wodaabe nomads find love

Because little did I, an awful dancer, know that in the remote Catholic village of Bancea, a tiny settlement on the western side of Poso Lake—Indonesia’s third largest—in central Sulawesi, one must dance to be accepted by the indigenous Dero people.

“In Bancea, dancing is social etiquette: During an acara [a communal event] we get to know each other and open to strangers,” Annie said when we first met in the home of the kepala desa (head of the village). Kit and I rolled into Bancea on our folding bicycles after tackling a punishing mountain pass, just as darkness was setting in.

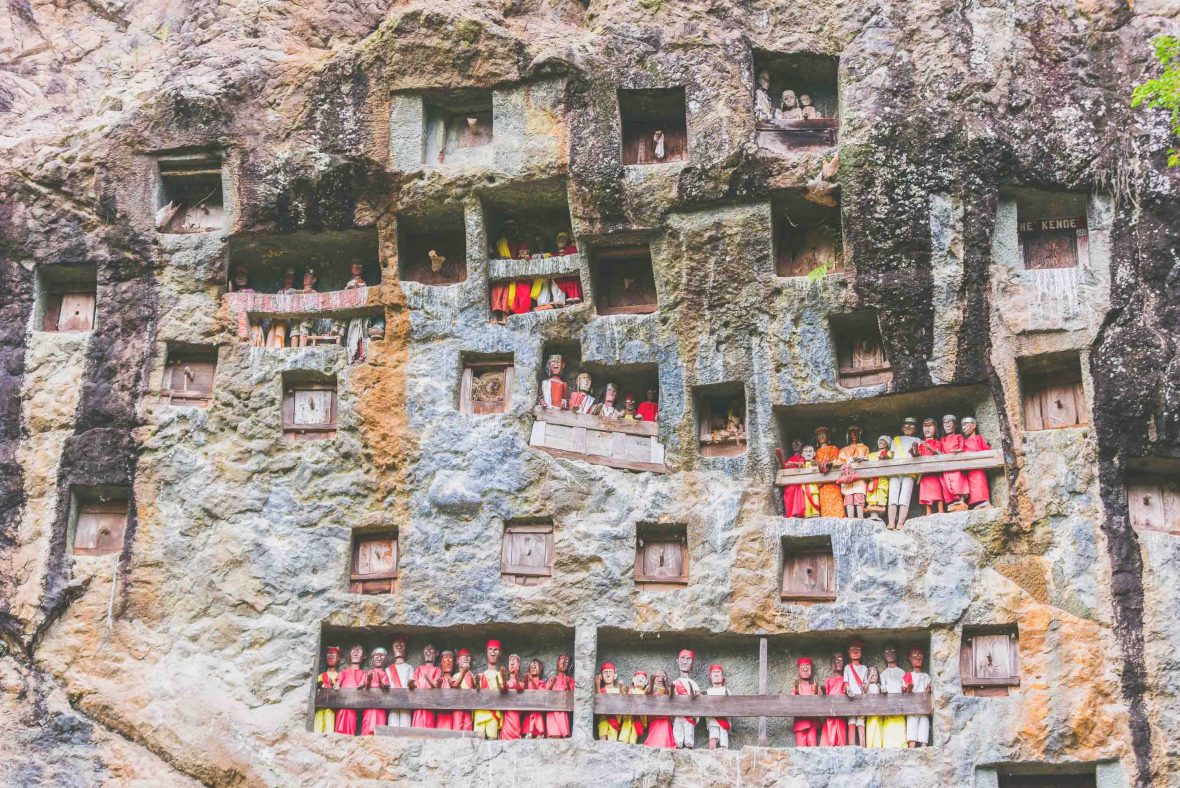

A bad name is hard to shake off, but this slice of green hills and jagged peaks has been conflict-free and perfectly safe to visit since 2012. Wedged between the Gulf of Tomini and the unspoilt, rainforest-clad Togian Islands to the north, it’s an ideal point to break up the journey south to Tanah Toraja and its gory funeral rites, Sulawesi’s most famous attraction.

We would have never expected, however, that to the indigenous Dero people of Bancea, the only way to warm up to guests is to line dance to the sounds of dangdut—popular Indonesian music that blends eastern rhythms with techno beats.

“Would you like to come to our acara?” the children and adults around us asked, their faces full of elation. They point to a house down the road, from where pounding music echoes into the night. “You can’t miss our party!” they insisted.

Tired and still wearing our sweaty cycling clothes, we followed a swarm of happy kids down the road. Just around the corner, a circle of villagers occupies the street, swaying in the dim reflection of the houses’ neon lights.

We have stumbled upon a Dero dance: It harks back to the olden days of the Poso region, once known as Bare (or Eastern Toraja), a land of looting headhunting tribes. After European missionaries came to evangelize central Indonesia, the warring locals transformed into the pious Christian groups, which are now known collectively as the Pamona people. But the Dero dance remains—ingrained as a liminal leftover of their tribal past.

RELATED: How to travel like a travel writer

In his book Anthropology and Egalitarianism, professor of anthropology Eric Gable describes the Dero dance as a long, tedious affair performed by two groups of competing youngsters who sang songs and danced in circles for hours on end. Dero dances were the only way the young Pamona could get out of their homes, let their hair down and meet new friends—both romantic and platonic—from nearby villages.

In today’s Bancea, the folk songs traditionally filled with sexual innuendo—once the core of any Dero dance—have evolved into dangdut. The ritual has become a village celebration that the residents prepare for together—cooking, chatting and playing cards the whole day.

For locals, dance is still vital to get out of the house and party—and in this case, also test and accept (or reject!) us foreigners into their own community. That’s why Annie grabbed me from the safety of my seat, and why I’m now being laughed at by an old man.

“C’mon, have you ever danced back in Italy?” Annie says before breaking into laughter. When she finally releases my hand and I can return to my plastic chair—to safety—the assembled crowd still gives me a round of applauses regardless. Though I’m not sure I’ve earned it.

Annie pulls up a seat next to me shortly afterwards. “You are lucky to have her,” she says pointing at Kit, who’s still bopping around between two other Bancea girls. “She can dance like a Dero,” Annie adds with a hint of pride before looking back at me. “Don’t worry. Tomorrow I’ll show you again. We have another acara coming up, and you are both invited as guests of honor.”

Frankly, I don’t know if that’s good or bad news.