Editor’s note: This article was published before the coronavirus pandemic, and may not reflect the current situation on the ground.

They’ve been called ‘the vainest tribe in the world’ and, once a year, Chad’s Wodaabe nomads get dressed up and dance for hours in the stifling sun in an attempt to attract a mate. Photographer Tariq Zaidi pays them a visit.

Dawn breaks in the semi-desert Sahel region of landlocked Chad. Nearby, a woman is already shaking a calabash, churning the cow’s milk into yogurt for breakfast. Work begins early in the desert.

But today, the nomadic Wodaabe will not just tend to their cattle, or pack up their rudimentary shelters and start moving to new pastures. It’s 6am, and one herdsman is already applying his ochre-red foundation in anticipation of tonight’s festivities: It’s Gerewol time.

The nomadic Wodaabe tribe, made up of subgroups of the Fulani people who have migrated along this part of central Africa for centuries, graze their cattle through the Sahel desert from northern Cameroon to Chad, Niger and Nigeria. Crossing countries riven by drought, poverty and war, they shelter in the most basic of structures with few possessions and are totally dependent on their animals for survival.

RELATED: Inside the lives of Mongolia’s last nomads

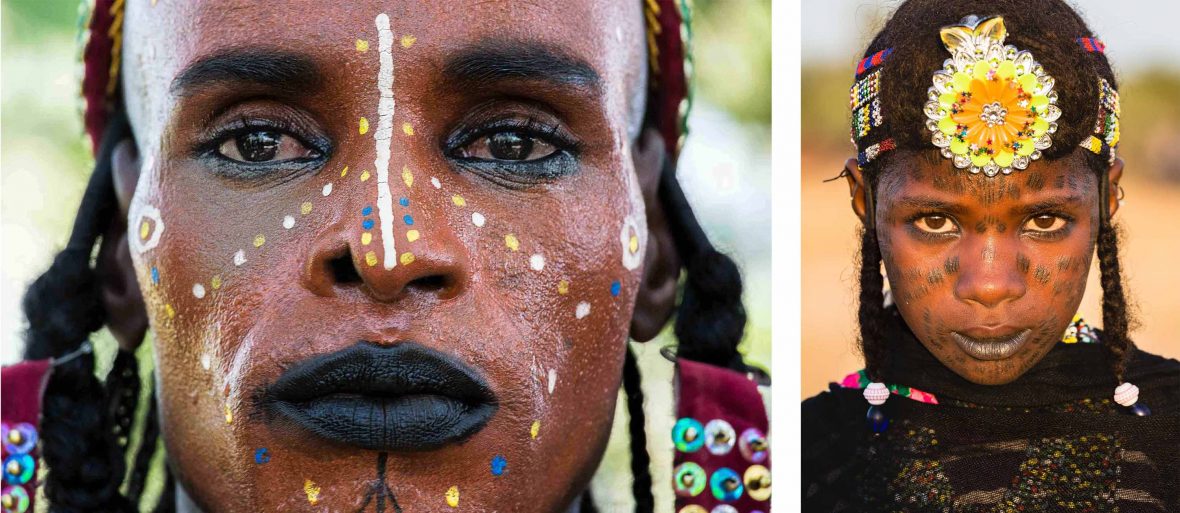

And despite the harshness of their environment, it’s beauty that the Wodaabe prize above all else. That’s why, once a year, for the Gerewol festival, an annual courtship ritual-meets-beauty pageant, the men don elaborate costumes, daub their faces with make-up, and dance for hours in the heat in the hope of finding love.

It’s a beauty contest unlike any other. In 50-degree-Celsius heat, they will perform a teeth-gnashing, eye-rolling dance in front of the women, in the hopes of being judged the most beautiful. Wodaabe women look for tallness, white eyes and teeth, a slim nose and a symmetrical face; the mens’ make-up, clothing and facial expressions accentuate these features. And because beauty and sexual attraction is all-consuming here, as a people they are incredibly liberated.

In fact, the Wodaabe must be the only African culture which allows girls to take the lead in choosing their betrothed—even married Wodaabe women have the right to take a different man as a sexual partner. While the focus of the Gerewol is very much on the men, women still take great pride in their appearance. Tattoos on the womens’ faces are from scarification at a young age and indicate a woman’s tribal affiliations, as well as her strength and valor.