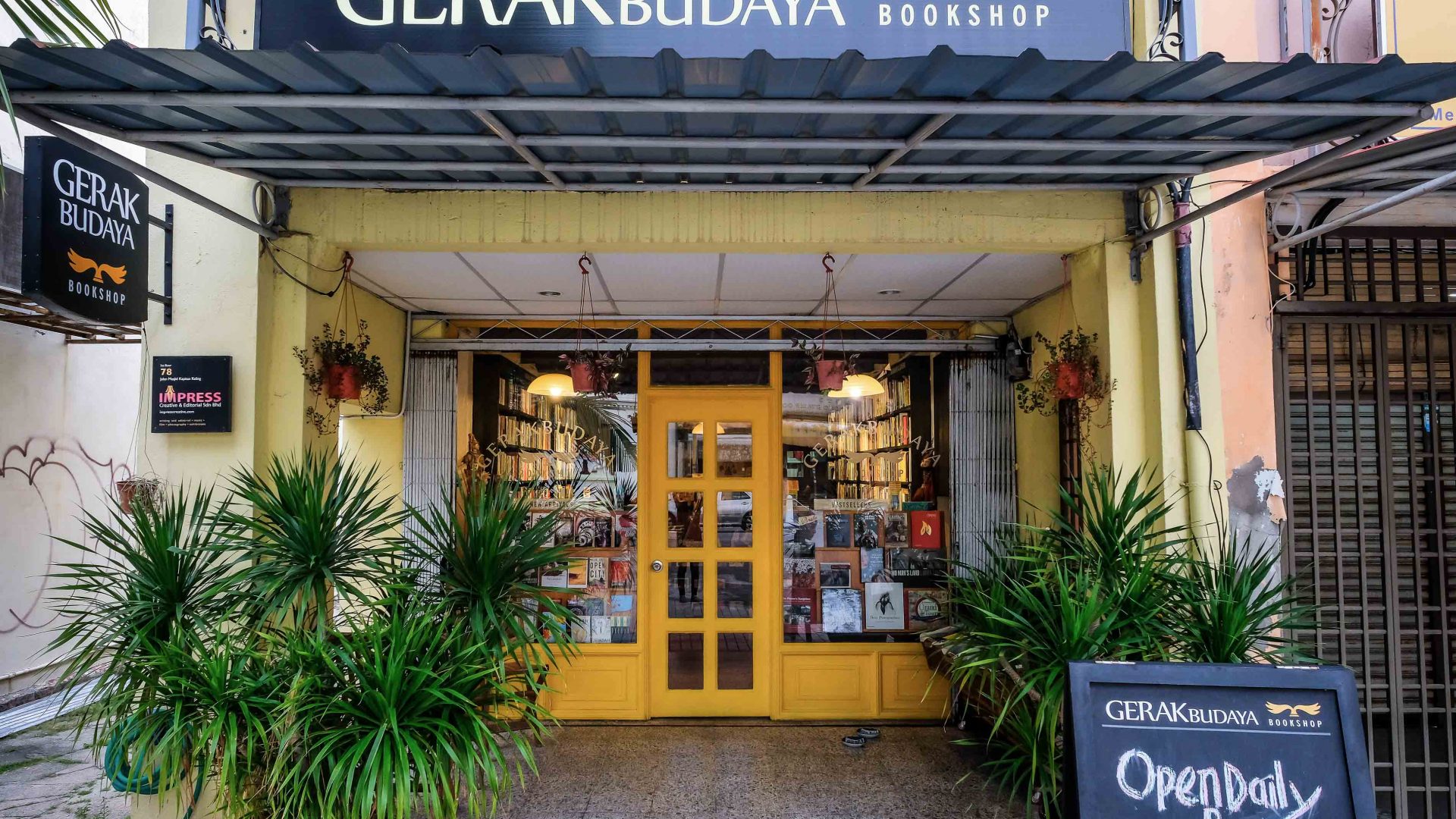

Long-term resident Marco Ferrarese knows that there’s much more art to Penang than selfie-perfect murals and gentrified streets. It’s all simmering under the surface of this UNESCO-listed Malaysian island.

Gripping their cameras and selfie sticks, a gaggle of sightseers walks single file down an alley that leads to the sea. They just parked their rental bicycles after the mandatory stop in nearby Armenian Street, one of George Town’s most gentrified streets. It’s here, in this UNESCO-protected city on the northwestern Malaysian island of Penang, that the ‘Little Children on a Bicycle’—an award-winning, world-famous mural mixing painting and a real-life bike installed into the wall—has been attracting long queues of international tourists on a daily basis since 2012.

Tourists also flock to the Chew Jetty, a rickety wooden plank flanked by two opposite rows of atmospheric wooden houses on stilts. Built by Penang’s early Chinese settlers to escape the onerous land tax imposed by the British rulers, Chew Jetty has turned into a microcosm of overtourism.