Iceland is often touted as the poster destination for overtourism, but Emma Thomson discovers an alternative Icelandic route for those keen on exploring without the crowds.

‘It’s overcrowded,’ say travelers to Iceland. In under a decade, the island’s visitor count has risen from half a million to 2.3 million—that’s more than six times the local population.

And while the numbers are startling on paper, most of those travelers can be found somewhere along the Golden Circle, a 300-kilometer loop around southern Iceland.

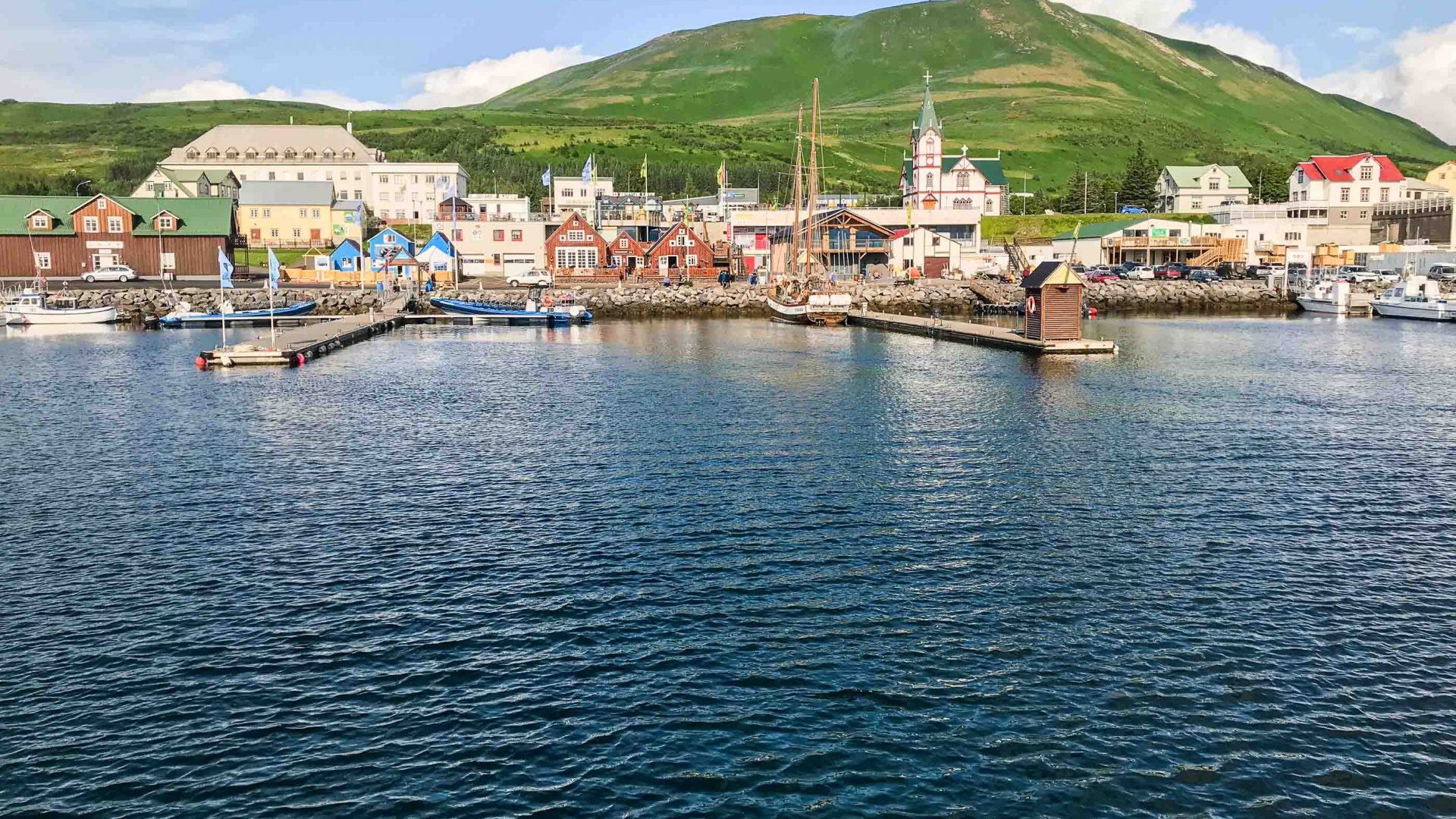

Nevertheless, the impact is real, so to rebalance tourism and showcase the country’s whale-rich, magic-filled north, the government has breathed new life into an existing road network that traces every inlet and rugged hillock of the Atlantic-carved northern coastline. And they’ve called it the Arctic Coast Way.