18 days, 300km, 1 swag, 0 showers and a billion blowflies makes for one hell of a journey.

18 days, 300km, one swag, zero showers and a billion blowflies makes for one hell of a journey. Especially if that journey takes place in the Simpson Desert, recalls Australian travel writer Jo Stewart.

When I tell people I once walked 300 kilometers through Australia’s Simpson Desert with a camel caravan supporting a scientific expedition, I’m immediately bombarded with questions.

Living and working in one of the world’s most inhospitable environments without access to showers, toilets, running water, Wi-Fi and the electrical grid may seem incomprehensible to some, but with careful planning, meticulous preparation and a bit of true grit, is totally possible.

Related: What doesn’t kill you: Why we need to embrace Australia’s ‘terrifying’ nature

Apart from blistered feet and questionable body odor, here are a few things I took away from the journey:

5. Restaurants are overrated

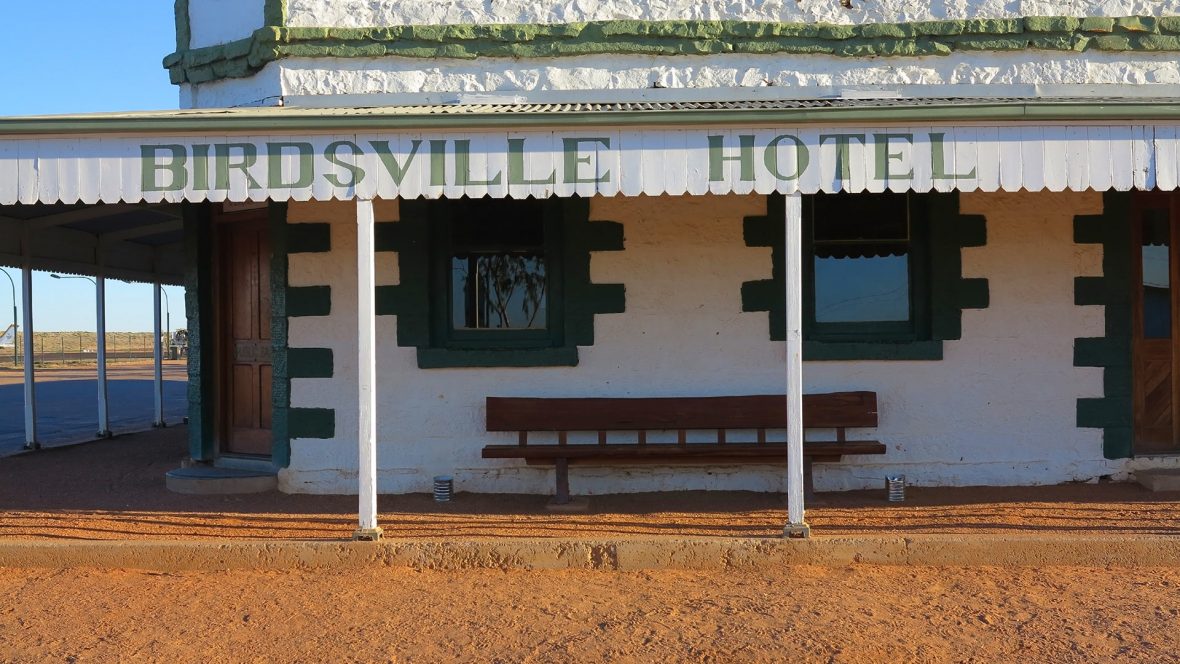

Ahhh, food. The greatest concern of most people, whether traveling in Brooklyn or Birdsville, food takes on an altogether new meaning when you’re on an expedition. When you’re midway through a 300km+ walk, food becomes an obsession. Way out of the range of the Uber Eats network and with no cheese drops from planes (no matter how hard we wished), our expedition had to be 100% self-sufficient.

Carrying tinned food like vegetables, tuna and beans plus rice, pasta and other items that don’t spoil, enabled the inventive camp cooks to whip up hearty meals. Items like preserved beef mince and chicken may seem weird, but when there’s no other option, a newfound love of dehydrated meat and reconstituted peas takes over. Out in the desert, flour, salt and milk cooked in the coals of the fire and covered in jam (and a few flies) tastes as good as anything you’d get from a fancy patisserie in the city.

6. Access to fresh, running water is underrated

Our trusty camels carried all the water we needed for the trip, and we rationed it as if it was the apocalypse. With water primarily reserved for drinking and cooking, there were no showers, excessive hand washing or washing of dishes. We used one enamel camping plate for breakfast, lunch and dinner and after each meal, we were given a piece of paper towel to clean our plate and cutlery. Maybe a tiny splash of water if you’d eaten something particularly hard to shift (note: don’t let your leftover Weetbix dry onto your plate, else you’ll be using a Swiss Army knife to chisel it off). Carried in jerry cans by our camels (who drink 50 litres all at once before the trip, then never again until the end), I’ve never looked at water the same way since returning.

7. Camels are the best/worst travel companions. Ever

The ships of the desert that made up our motley crew were majestic yet temperamental beasts, prone to flicking urine around with their tails and spitting green, masticated leaf slime in our faces. They made the journey possible with their feats of strength and endurance, but sure did take liberties whenever they could. Regardless, I’d rather travel with a pack of camels than a busload full of tourists any day of the week.