Some 16 years ago, a Canadian hiker decided to create a long-distance trail on Vancouver Island. Today, the 800-kilometer trail is almost complete, a winding trail passing mountains, logging roads, rugged coastlines, and the territories of 49 First Nations. Brendan Sainsbury tests out a section and speaks to those involved in its creation.

It was an ambitious plan. In 2005, Gil Parker, a lifelong Canadian climber and hiker fresh from completing the 4200-kilometer Pacific Crest Trail in the US, came up with an exciting idea: to create a similar long-distance path on his native Vancouver Island. The adventurous route would help link communities, stimulate recreation, and awaken outsiders to the island’s largely hidden natural wonders.

Making the dream a reality was a daunting prospect. Vancouver Island extends for 456 kilometers, from the city of Victoria in the south to rugged Cape Scott in the north. Traversing it on foot meant constructing a continuous 800-kilometer-long path, zigzagging through a mix of crinkled mountains, private logging roads, storm-lashed coastline, and the territories of 49 First Nations.

Unintimidated, Parker, a retired structural engineer, formed a non-profit body called the Vancouver Island Trail Association (VITA) and set to work. Today, some 16 years later, after numerous donations and countless months of hard labor by a small army of volunteers, the Vancouver Island Trail (VIT) is over 90 per cent complete.

In June 2020, as the restrictions of COVID-19’s first lockdown were eased, I traveled to the Vancouver Island Trail’s inauspicious start point in suburban Victoria with the intention of surveying the first 100 kilometers of the route on a bicycle. As it turned out, I wasn’t the only curious traveler.

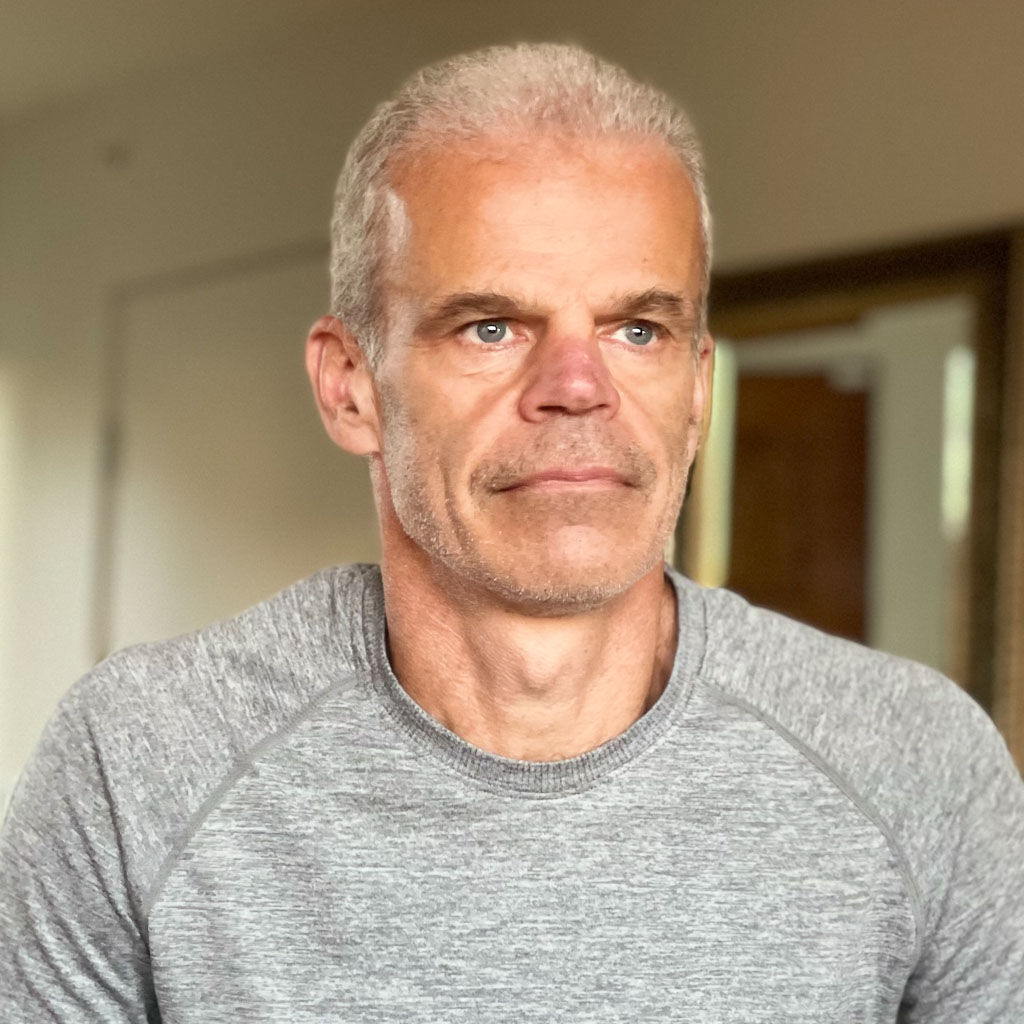

“Since COVID-19, statistical analysis has shown that a significant number of people have become more interested in getting outside,” says Liz Bicknell, current president of the VITA (Parker stepped down in 2017), alluding to a flurry of recent interest in the trail. Nine through-hikers have tracked its entire course in 2021, despite the fact it’s not yet officially complete.

RELATED: How lockdown—and birding—changed the way I hike

Working closely with logging companies, First Nations groups and tourism associations, Liz is in the process of finalizing administrative and legal agreements before the trail can be formerly opened. “We’re aiming for completion in 2023,” she says. “If you don’t set goals, you will never reach them.”

With 180 kilometers of the trail passing through private land, Liz has recently signed a memorandum of understanding with BC timber company, Mosaic, and is slowly developing respectful and mutually beneficial relationships with the Songhees, Namgis, Kwakiutl, and other First Nations.

Indigenous land issues are complex and sensitive, and the traumatic history suffered by Canada’s indigenous people was recently acknowledged in the country’s first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation on September 30th 2021.

Liz is emphatic about the VITA’s desire to incorporate indigenous world views and ways of knowing into the path’s evolution, as well as promoting economic development opportunities from the Indigenomics Institute, a research and engagement platform that supports the rebuilding of indigenous economies worldwide.

My own journey on the trail was refreshingly straightforward. After pedaling through the suburbs of Victoria, I followed the VIT on a well-defined path shared with the iconic Trans-Canada Trail as far as Lake Cowichan.

Beyond metro Victoria, Vancouver Island quickly dissolves into quiet wilderness crossing the Koksilah River on the magnificent Kinsol Trestle, a 44-meter-high railway bridge saved by a community fundraising campaign in 2011.

RELATED: Paradise trekked: Fiji is a hiker’s wonderland

By lunchtime, I was enveloped in thick forest; by late afternoon, I had logged two bear sightings. Notwithstanding, this southern portion of the Vancouver Island Trail is considered one of the easier sections.

“The trail is more challenging in the island’s remote north, once you leave the well-established path network of Strathcona Provincial Park,” explains Terry. “Here, you have to be capable with GPS as there’s one small section with no markings.”

For Alex, the trail was a perfect balance of challenge versus enjoyment. “There were tough and technical stretches, but it was exciting, and you pass through civilization again in under a week if you need a breather,” he says.

Strathcona Provincial Park, a 2458-square-kilometer potpourri of mountains, waterfalls, and glaciers in the center of the island was a highlight.

“It was just fantastic to traverse these high routes surrounded by snow-capped mountains and forested plateaus,” he adds. “It was more extreme than the preceding sections, but it was also far more rewarding and felt like a real wilderness experience. You haven’t really seen the stars until you are out in the park on a clear night, tens of miles away from any houses.”

Passing through every facet of the island’s ecology and culture, the scenery along the trail oscillates dramatically as you track north, from the industrial relics of erstwhile railway infrastructure near Victoria to the giant stands of old-growth Douglas Fir north of Strathcona, some of which are up to 70 meters high and as old as medieval castles.

First Nations culture is everywhere. The VITA recently reached an agreement with Indigenous groups to compile a map depicting the island’s different language groups and install information panels in strategic locations cataloguing their history.

For its final 58 kilometers, the VIT merges with the North Coast Trail, a wild coastal domain of fickle weather that abuts the Pacific Ocean where black bears stalk log-strewn beaches and whales breach in turbulent seas. According to Alex, this is the most social part of the trail where you get to hang out with other camping hikers in the evening.