The four-day wukalina Walk takes travelers across the northeastern coast of Tasmania, and into the heart of local palawa culture. Tayla Gentle laces up her boots and retraces tens of thousands of years of history on this Aboriginal-owned-and-operated experience.

Content warning: This story contains references the mistreatment of Tasmanian Aboriginal people, including sexual abuse, that readers may find distressing.

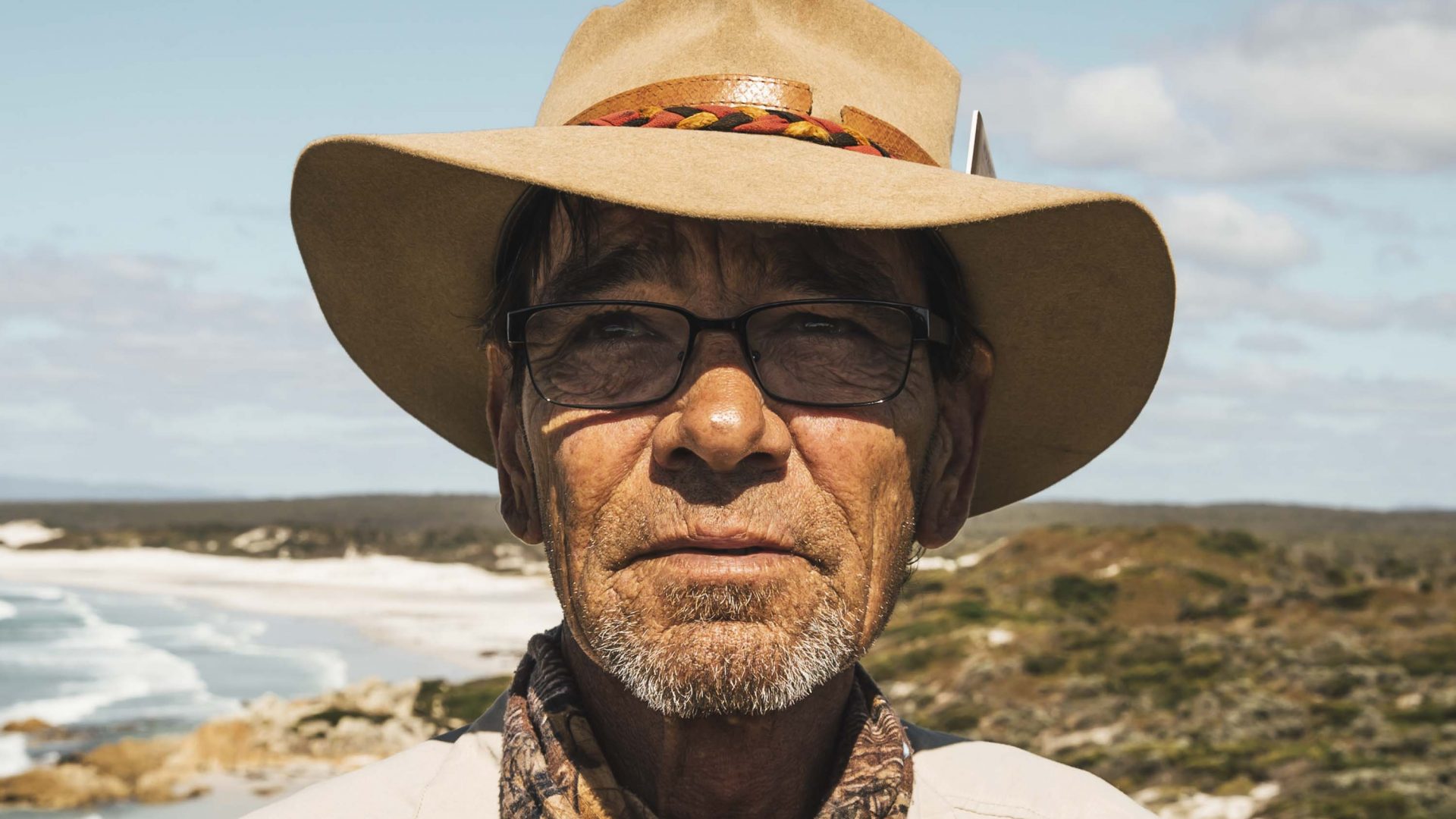

Yesterday, I was chewing on snake tongue grass. This morning, I walked a chalk-white beach picking saltbush for dinner. And right now, I’m rubbing muttonbird oil into my wrinkle lines because it’s a traditional Tasmanian Aboriginal moisturizer. At least, that’s what my palawa guide, Uncle Hank, tells me.

Before this week. I’d never chewed on snake tongue grass, picked saltbush or even heard of the muttonbird—a small, quail-sized bird that flies all the way from Antarctica to roost at the tip of Tassie— let alone grilled one on an open fire and used its fat as a skincare product.

But I’m on the wukalina Walk, a four-day Aboriginal-owned and operated trip across the pristine northeastern coast of Tasmania, and I’m quickly realizing that this is a cultural deep-dive like I’ve never experienced before.

I’m joined by three palawa guides—Uncle Hank, a respected elder; Jam, his softly-spoken assistant guide fluent in all things flora, fauna and palawa kani (local language); and young Ash, a protégé of sorts, here to learn more about the traditional ways and train to be a guide. As a trio, they’re calm, articulate and incredibly willing to share their culture and living history.