Where will Trump’s attack on public lands end? Here’s everything you need to know about the Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante land grab, and how you can help protect these sacred national monuments.

A drive down a dirt road that threatened to bottom out my Kia Soul and one single day hike through a narrow canyon; the walls looking like massive sculptures of red and tan clays, the cottonwood trees’ leaves a brilliant yellow.

That’s all it took for Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument to carve a permanent space in my mind as a place I wanted to explore time and again. But unless I move to Utah and devote myself to Grand Staircase full-time, I’ll never know it as deeply as I would like: The National Monument is huge.

Or, make that, was huge; 1,880,461 acres huge, to be precise. On December 4, President Trump issued a proclamation slashing Grand Staircase’s size by half while also decimating Bears Ears National Monument, also in Utah, by 85 per cent.

Both areas are loved by the adventure community as places to hike, paddle, bike, and much more; and to scientists who value the chance to study geology, plants, and animal life in areas untouched by development. But Bears Ears’ greatest significance is as a sacred place for Native American peoples.

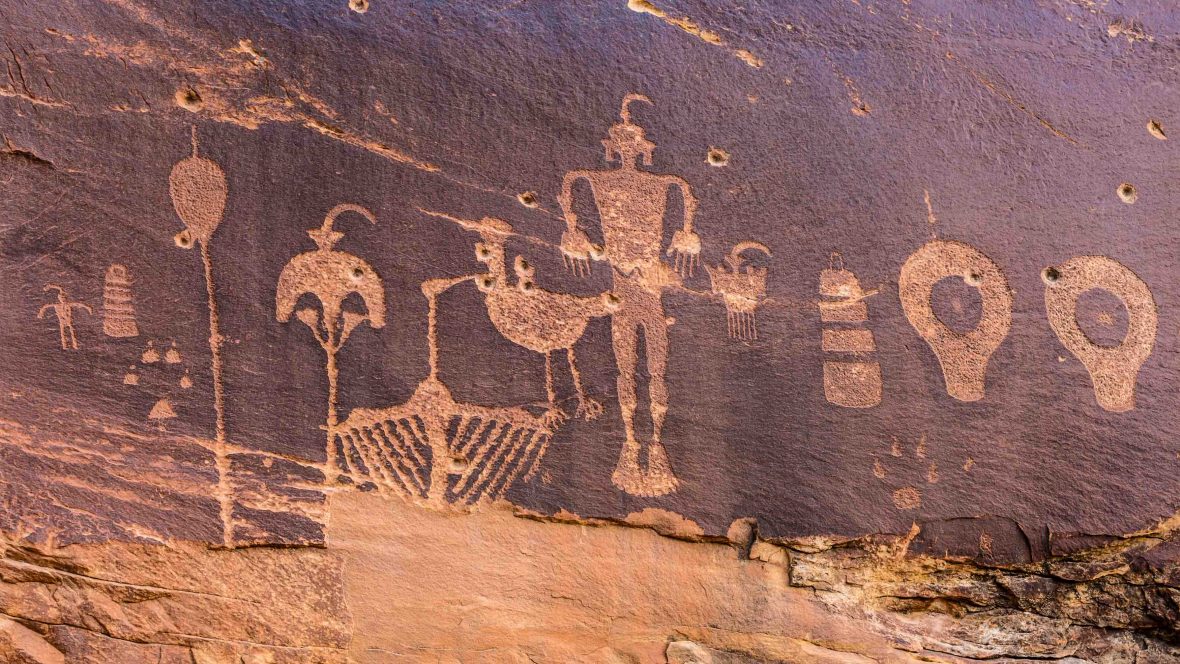

More than 100,000 areas of archaeological and cultural significance pepper the 1.34 million-acre monument. Some of the rock paintings, petroglyphs, historic structures, and other artifacts date back thousands of years. It’s for all these reasons that each was declared a national monument—President Clinton added the protection to Grand Staircase in 1996 and President Obama did the same for Bears Ears just last year.

None of this intrinsic value seemed to matter to President Trump and Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke as they redrew the boundary lines of the two national monuments. Instead, the federal government has made it clear that it’s far more interested in cashing in on the resources that can be pulled out of those areas instead of protecting the value of what’s in them.

“Some people think that the natural resources of Utah should be controlled by a small handful of very distant bureaucrats located in Washington,” said Trump in his speech at Utah’s State Capitol. “And guess what? They’re wrong. Together, we will usher in a bright new future of wonder and wealth.”

Once changes are made to the physical lands, they can’t be undone. And it will take a strong opposing force to fight back. That’s where’s the public comes in.

Hartinger says that, as well as calling (and calling and calling) members of Congress to express your support for the Antiquities Act and displeasure at Trump’s changes, it’s important to talk to family members about these changes. The best way? Through storytelling. Detail your travels to national monuments. Share the joy of these lands. Show photos to friends that make them want to explore, too. And keep traveling to all national monuments (along, of course, with their big sibs, the national parks).

And, if you’re starting to feel fatigued on the fight-back front, Hartinger has some words of wisdom about what keeps him going. “First and foremost is the tribal leadership; their spirit, leadership, and resolve in the face of centuries of adversity. If they can keep this up, all of us can as well.”

—