Sure, you have to wear thick wetsuits to take a dip here, but below the surface of Scotland’s new ‘snorkel trail’ is a surprisingly rich marine life. Graeme Green takes the plunge to see what lurks beneath these ice-cold waters.

“People might think this is a crazy idea …” admits Daryll Brown, a ranger with the North Harris Trust, a community regeneration initiative. That’s always an ominous-sounding start to any venture.

We’re driving out from the village of Tarbert, the tiny capital of Harris—an island in Scotland’s Outer Hebrides—heading towards Hushinish beach, one of the key sites along a new snorkeling trail. “A lot of people don’t understand why we’d want to snorkel in this water,” says Daryll. “They think it’s going to be too cold and there’ll be nothing to see.”

It’s rich in wildlife above water too, from red deer and otters to a huge variety of birds, including sea and golden eagles, and it’s well-known for this. As we drive east to Hushinish, we pass the remains of whale bones from one of Europe’s few whaling stations, closed since 1950, as well as shaggy sheep and those iconic Highland Cows. En route to pick up wetsuits, snorkels and fins from the Scaladale Outdoor Activity Centre, Daryll detours to a car park by the ‘bird of prey trail’ at Bogha Glas.

“This is the best place in Harris to see both kinds of eagles,” he tells me, studying the misty hills for movement. “Harris has 13 pairs of breeding golden eagles; the largest population in the UK.”

RELATED: Coral bleaching and the Great Barrier Reef

But Harris’ underwater landscapes and creatures are as interesting as those on land and in the sky—but snorkeling isn’t exactly common on the island. Those who do go underwater tend to go for food, as the waters are rich with crabs, scallops, lobster and more. “People don’t associate the local waters with such colorful marine life,” Daryll explains.

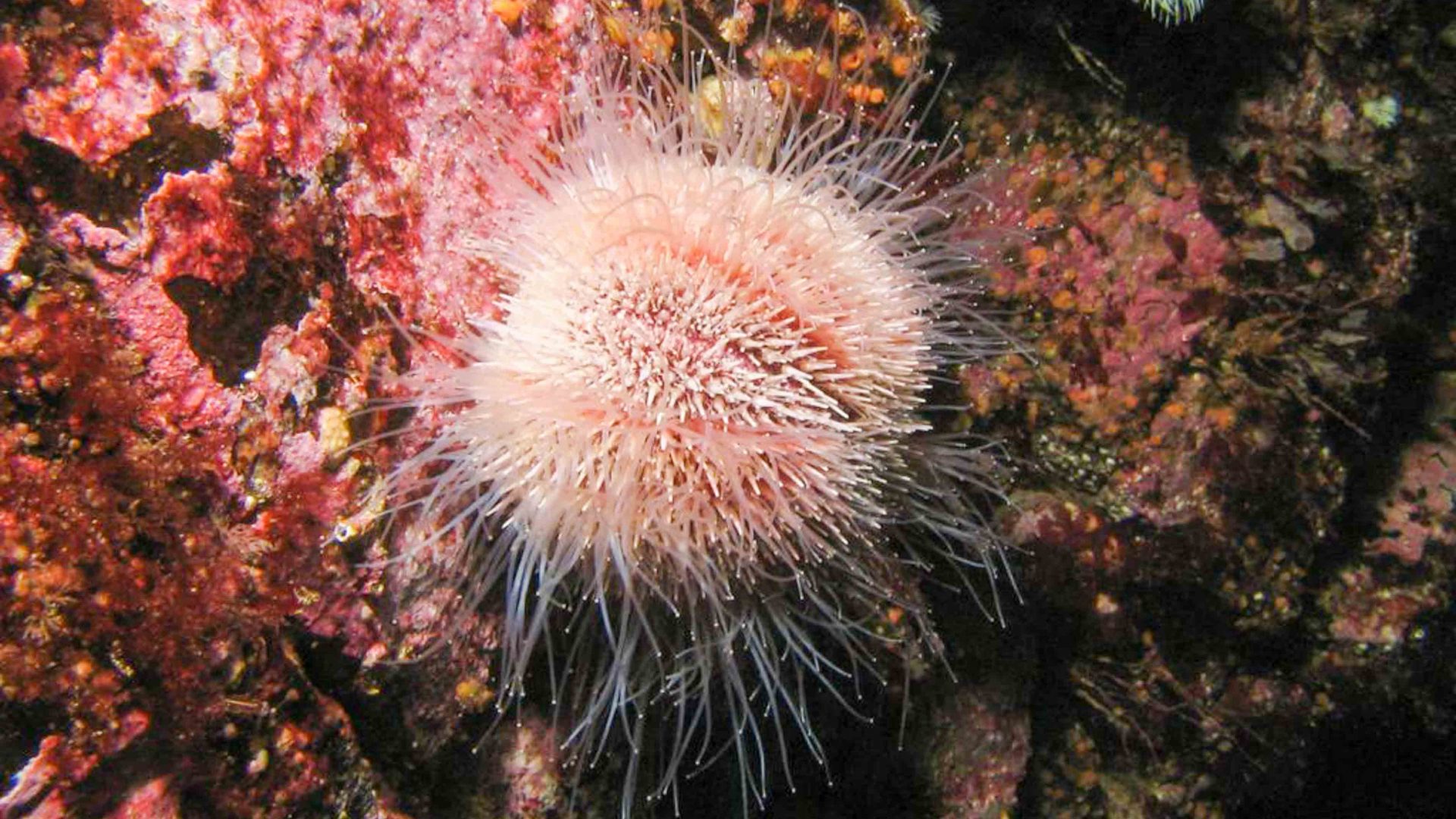

The new trail though, he says, aims to highlight different environments around the North Harris coastline. “We have sea grasses like you’d find in the Caribbean, and tons of starfish, urchins, different fish. Sometimes we see basking sharks. You get a lot of whales here—minke, fin, humpbacks, sperm … And dolphins, common seals and grey seals. There’s a really rich set of marine life to see.”

As we change into 6mm wetsuits and hoods, lashed by a strong wind and the waves crashing white off Hushinish, it does feel slightly crazy to be going for a swim. Average water temperatures for the sites range from 8.5 degrees Celsius (43 degrees Fahrenheit) in February and March, to 15 degrees (60 degrees) between August and October.

The local waters can, Daryll promises, be “bathwater” warm on a sunny summer’s day. That wasn’t today though. For us, it was rainy and grey. “The water’s about 12 degrees at the moment, so it’s not freezing.” It’s a valiant attempt to reassure me.

Weather plays a big role in any outdoor activity on Harris, so when designing the trail, Daryll selected six spots in safer, often warmer, sheltered bays. With slightly stormy conditions on our day, we try two sites that he judged as safe and reasonably easy to explore.

Geared up in snorkels, masks and fins, we walk backwards into the water. Submerging myself for the first time was jolting, the cold water punching the air from my lungs. But my body quickly adjusts, the wetsuit keeping me warm (ish), and I begin to enjoy the bracing swim around the bay.

Long golden leaves of kelp move below us, waving with the movement of the ocean, almost alien-like, as if in a sci-fi forest. Another underwater plant, known as bootlace weed, stretches up from the ocean floor, like giant ponytails, and large crabs scuttled about. “It’s a magical landscape,” says Daryll back at the surface. “And it changes so much with each season.”

Daryll points out the sugar kelp, the same one used in the gin made at the island’s newly opened Harris Distillery. There’s plenty underwater that’s edible too, he explains, presenting us with plants such as sea lettuce to nibble on and try. Having Daryll as guide and ‘interpreter’ helped bring each place to life, and while the trail is largely designed for self-guided trips, guided snorkel tours are expected to start in the next year. For now, guided tours of the snorkel sites are open to school and youth groups.

Making our way in the car from Hushinish to the next site, we stop to watch a large sea eagle soaring over the hills before reaching Seilamol Bay and heading down the boggy hillside to the beach. “We’ve got everything here at this site: starfish, scallops, sea urchins …” says Daryll, clearly excited. “There’s so much to see.”

RELATED: A deep dive into an underwater art world

The water is greener, murkier and a little colder, but it’s another fun, colorful swim. Daryll carefully carries a giant edible giant crab up to the surface for us to take a closer look. It would’ve made a fine feast—but we let him go on his way. Scallops moved about beneath too; Daryll points to the outline of their shells on the sandy floor far below.

That wasn’t all. As we swim over a kelp forest and explore from one side of the bay to another, four different varieties of starfish add to our bounty, including a bright purple specimen that clings onto the palm of my hand, along with pollock and a school of small silvery sand eels.

Back in warm dry clothes, we head back towards Tarbert. Daryll takes out his binoculars at the sight of another large bird ahead of us.

“That’s a goldie,” he says, confidently. “That’s a beauty. 2.2-meter wingspan, an adult.”

It’s quite a sight, and as it glides along the coast, it’s easy to see why the iconic ‘goldies’, sea eagles and deer get so much attention from nature lovers. But, as the snorkel trail shows, there’s plenty more life on Harris, if you look beneath the surface.