What’s it like to snorkel between two tectonic plates in glacial waters? David Whitley squeezes into a dry suit—and explores a whole new (in-between) world.

At the water’s edge, the humiliation of being helped into a dry suit for what seems like hours suddenly feels like a worthwhile trade-off.

This is no ordinary snorkeling experience of flitting fish and swaying coral in warm, tropical seas. It is a plunge into the gap between two continents—a gap that happens to be awkwardly close to the Arctic Circle.

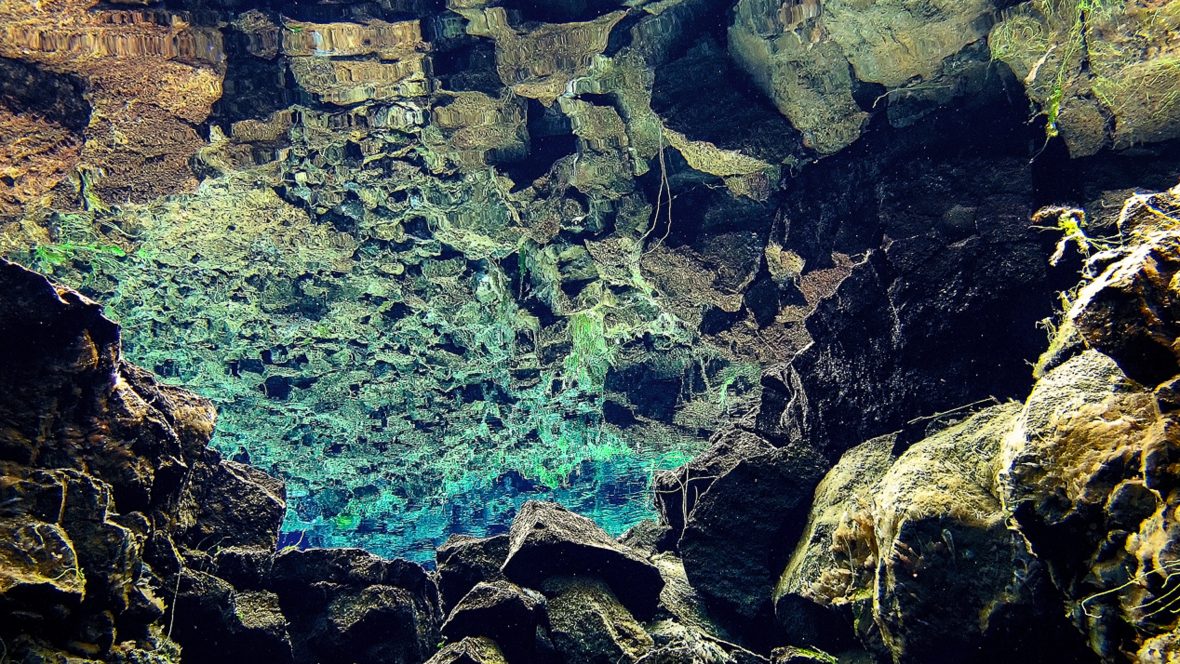

This is the Silfra fissure. Formed by the Eurasian and North American tectonic plates slowly ripping apart, it cuts through the Þingvellir World Heritage Site, a spectacularly bleak expanse of tuftily-mossed lava fields with stark mountains jutting up on the horizon and bone-rattling North Atlantic winds gusting through. It’s where Iceland’s first parliament—and the world’s oldest—first met in the 10th century; the national flag flies proudly beneath the intimidating rock wall.

Getting kitted up for a splash in Silfra is quite the rigmarole. Regular wet suits—which keep you warm by pressing water tight against the skin—will simply not cut the mustard in water that has trickled down from a glacier. So special dry suits worn over socks, shirts and long johns, are slowly wrenched on.

RELATED: Snorkeling in Scotland? Taking the (cold) plunge

Hands are forcibly shoved through armholes and into the gloves. Getting the head through the neck holes involves walking backwards as snorkeling guide Ásgeir, who looks like a heavily-bearded wildling extra from Game Of Thrones, tugs the suit into place. It’s a fairly degrading, helpless experience, but one that’s entirely necessary.

The only parts of the body that should get cold are the slivers of face left exposed and, possibly, the hands—if water gets into the gloves. “The less you move your hands, the better it will be,” reassures Ásgeir.

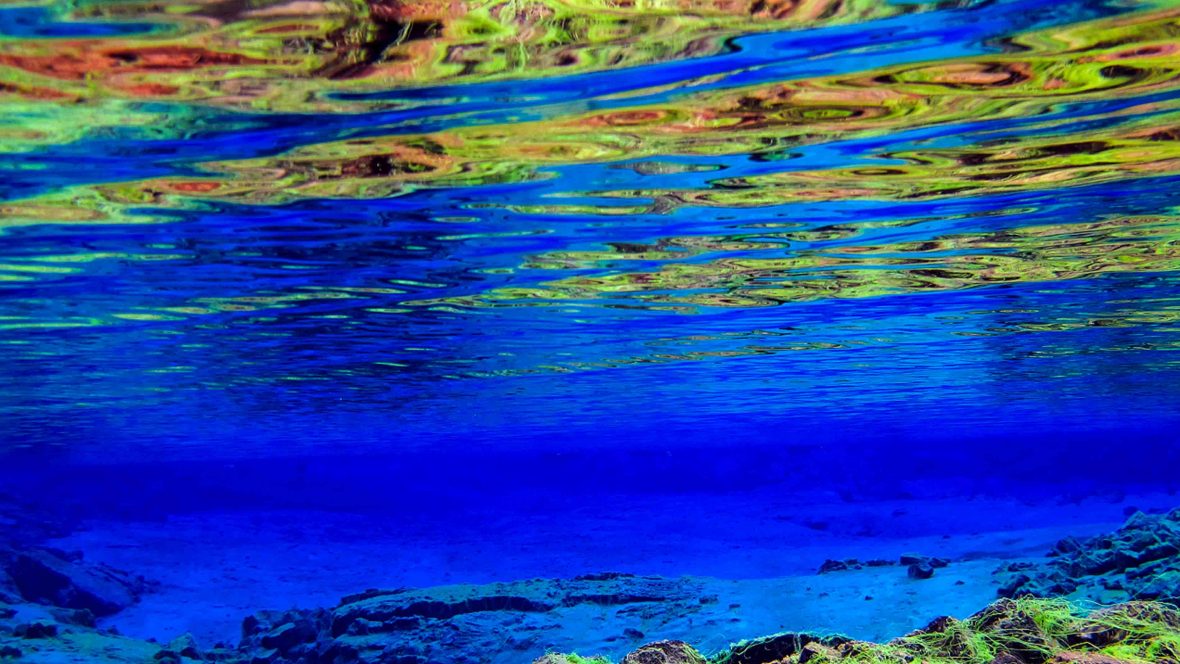

The clarity is extraordinary. To the left, to the right, and 63 meters down through bands of ever deeper blues, there is simply nothing to get in the way. No oily run-offs, soils, nutrients or sloshing mud. It is simply impeccable, and an open invitation for muffled “Oh my”s to glug their way to the surface through the snorkel.

RELATED: Alternative Iceland, far from the madding crowds

A few hardy fish species live in Þingvallavatn , but in the fissure itself , there is virtually no sign of life beyond the flailing legs in dry suits. There are little hair-like mossy coatings on the rocks, half-heartedly growing like wannabe seaweed, but otherwise, just humongous chunks of basalt. They’re piled on top of each other like they’ve been casually thrown in a skip, but they create the caves and canyons that make this a truly astonishing experience.

In the end, the gimmick—snorkeling between two tectonic plates—becomes secondary to the sensation. With the body insulated from the cold, and the ears unable to make anything out beneath the water’s surface, it becomes almost entirely about the soothingly simple visuals. Just rough-hewn rock walls and a vivid spectrum of blues.

Eventually, the effortless float reaches a little islet, which marks the point that everyone has to start putting some work in and swim back to shore. Only once out of the water do cold faces get noticed, and those icy winds score a hit.

As for getting out of a dry suit? Well, it’s just as undignified as getting in. But this time around, everyone’s far too awestruck to care.

––––