Even before the pandemic, the gigantic, gorgeous, hand-made Saraswati veenas of Southern India were at risk of extinction. Meenakshi J explores how this centuries-old instrument, and the craftspeople who make it, are trying to adapt with the times.

“Veena-making is a laborious process and involves a lot of skill and precision,” says 70-year-old M. Narayanan, one of the few remaining makers of India’s national musical instrument, as he welcomes me into his home and backyard workshop in Thanjavur, some 350 kilometers south of Chennai. “Our family has been conscientiously handcrafting this divine instrument for over three generations now.”

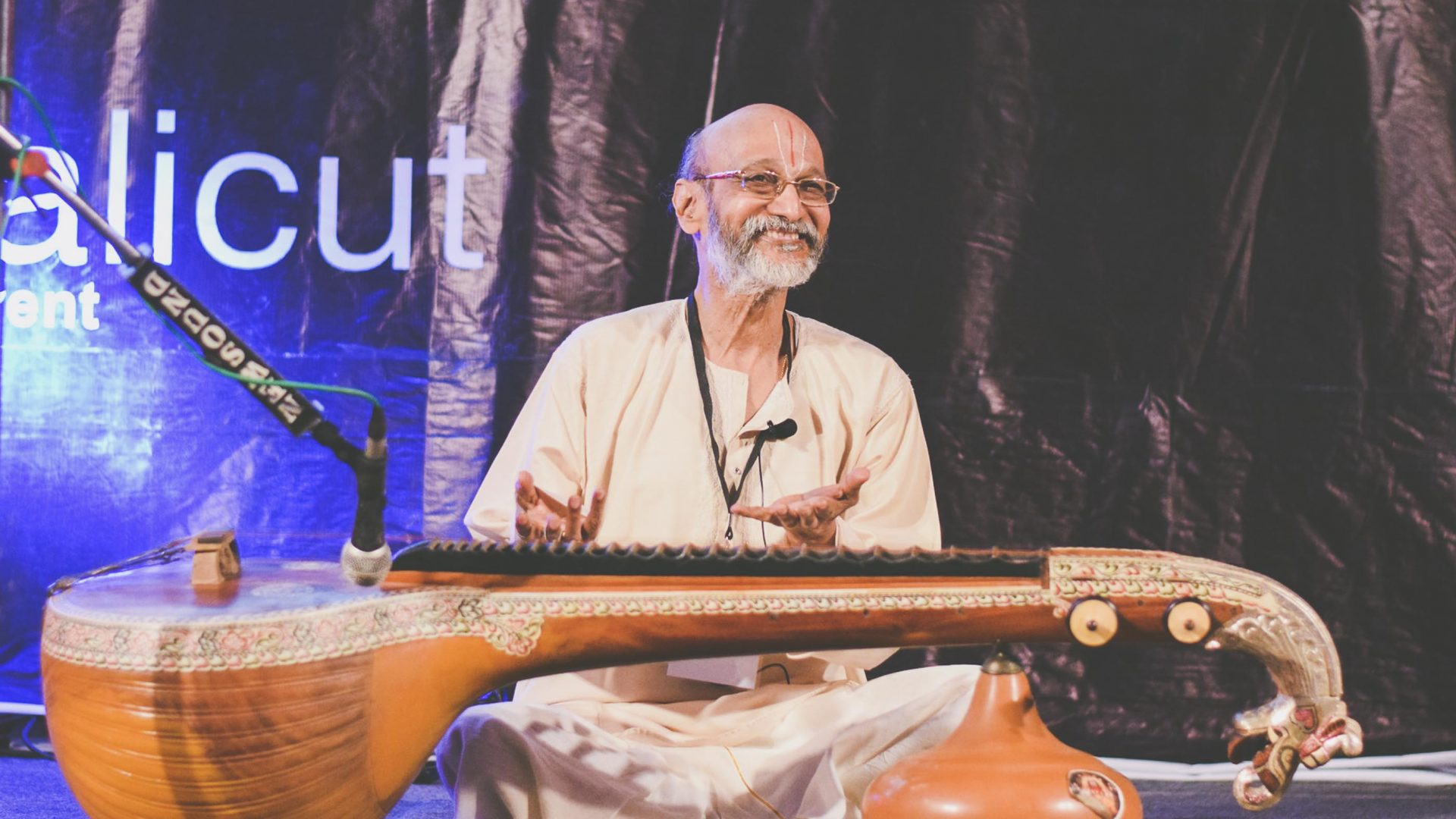

Diligently and skillfully cut, chiseled, shaped and assembled out of the highest-quality jackfruit wood, beeswax and charcoal, the Saraswati veena, with its four-foot-long wooden body, is considered sacred—and has even bagged the first GI (Geographical Indication) tag for any Indian classical instrument.

As Narayanan, who’s won awards for his craft, excuses himself to take a call, M. Murugesan, Narayanan’s apprentice for the last 40 years, pitches in. “Every handcrafted veena takes at least a month from start to finish,” he says.

For Narayanan and Murugesan, and the few remaining craftspeople like them, making this instrument is a labor of love, and turning passion into profit hasn’t been easy. “Of late, there’s been a dearth of good-quality jackfruit trees in and around Thanjavur as most of the groves have been converted to residential plots and sold,” says Narayanan on his return. “Escalating costs and difficulties in procuring raw materials are major reasons for a decline in this craft.”