Editor’s note: This article was published before the coronavirus pandemic, and may not reflect the current situation on the ground.

From protests and psychedelics to black power and AIDS, Ken Jones—a contender for the world’s most interesting tour guide—reveals the lesser-known history of San Francisco’s Castro District in the ‘70s and ‘80s.

Standing on a street corner, Ken Jones points out the gas station he crashed his car into one day in the ‘70s after having hallucinogens for breakfast. “The day always went well when we took LSD or mescaline,” he explains. “My partner was an acid dealer. We were well-known for our acid punch parties that started on Friday night and ended Monday morning.”

If it wasn’t clear before, it’s very clear

to me now that I’m not on your average San Francisco city tour. But then again,

Ken Jones isn’t your average tour guide.

I wasn’t looking to join a San Francisco tour, but when a 68-year-old civil rights activist, community organizer, not-for-profit founder and three-tour veteran of the Vietnam War decides to add ‘tour guide’ to his resume, you can bet I’m signing on. That’s how I ended up standing on the corner of Castro and 18th, hearing about the wild parties that made me wish time machines existed.

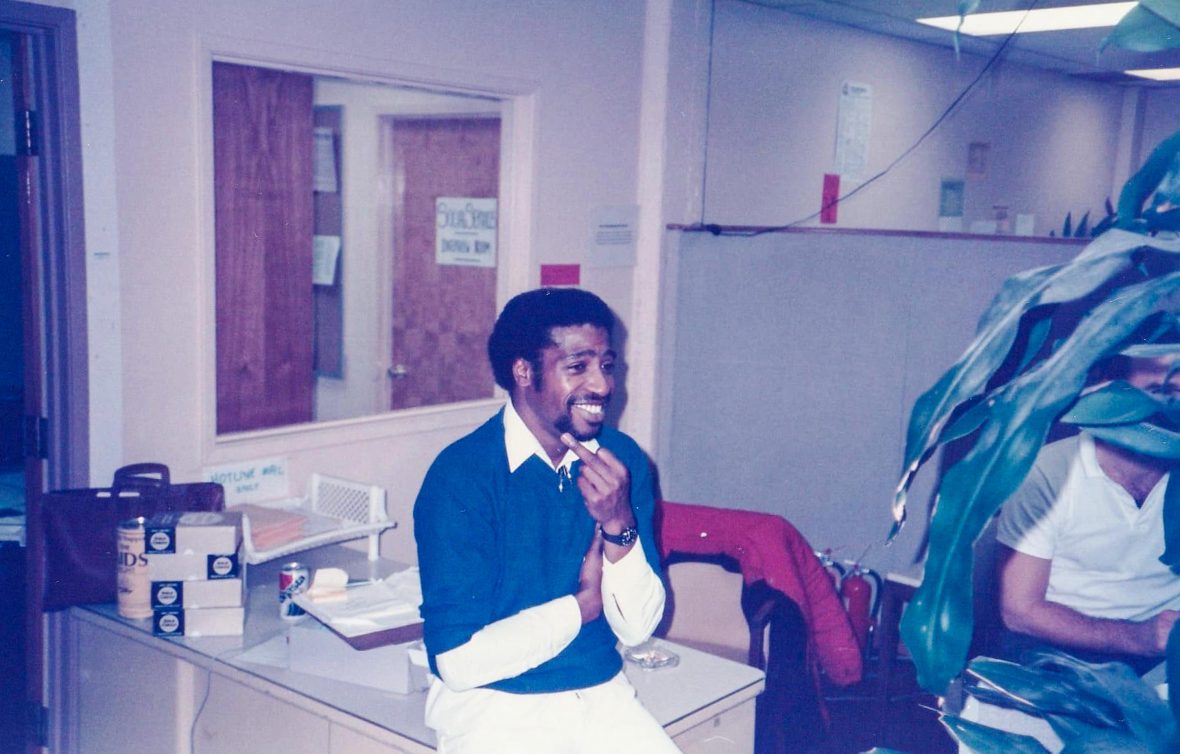

Portrayed on-screen by Michael K. Williams (aka Omar from The Wire) in the mini-series When We Rise, Ken is kind-of a big deal. Charting the lives of San Francisco’s change-making queer activists, the series pushed Ken to share his story with millions.

“I definitely overshared, but for the first time in my life, I had no more secrets, shame or self-hatred,” he says. “It’s not easy growing up black in white America. It’ll do a number on you. Telling my story gave me a dose of energy and new platform from which to speak.”

RELATED: The Vatican’s untold gay history

For a visitor, it would be all too easy to take a snap of Harvey Milk’s camera shop then move on, but a tour with Ken dives deeper, revealing hidden histories and poignant threads. We stop at a wall where Ken remembers that during the ‘80s, this spot was constantly plastered with images of Castro locals who had died from AIDS—a makeshift shrine and death noticeboard in one.

He also doesn’t shy away from complex issues. Standing under the rainbow flag that flies over Harvey Milk Plaza, Ken admits that he wasn’t always a fan of the flag. When he first laid eyes on the hand-dyed creation made by artist and activist Gilbert Baker in 1978, he hated it. “Gilbert was a member of a group called the Radical Faeries,” he says. “They were anarchists. They were also a pain in my ass.”

RELATED: When will the travel industry show more diversity?

Now, more than 45 years since the ubiquitous rainbow flag was born, Ken’s relationship with it has come full circle, with his tours beginning under the flag that once made him “lose his cookies.”

“I’ve observed a community come together under that flag. I’ve witnessed it become the symbol for a movement. My god, how powerful that is. This flag has gone from our pole in The Castro, out into the entire universe.”

Now living in San Francisco’s Fillmore District, Ken’s witnessed The Castro change since he arrived in the 1970s. With concerns that the area is losing its radical edge, does he worry about the Castro district’s future?

“The Castro will always be a gay gathering place. That corner of Castro and 18th is our mobilization point,” explains Ken. “The faces may change, the ages may change, but we all know that’s where we find people when we need them.”

Proving that old activists never really retire, Ken is still fired up about making The Castro the very best it can be. Replacing the gas station (yes, that gas station) with a farmers’ market, reinvigorating Harvey Milk Plaza, and developing a new tour that honors the legacy of ground-breaking disco artist Sylvester are all on Ken’s agenda. “I’m running into brick walls … but I’m going to keep trying,” he beams.

—-