Editor’s note: This article was published before the coronavirus pandemic, and may not reflect the current situation on the ground.

Every year, some 30,000 camels descend on Pushkar, a small town in the state of Rajasthan, in what’s been billed as India’s “greatest tribal gathering”. Photographer Annapurna Mellor captures the madness.

Gazing through his long, sandy eyelashes, the beast stares curiously into my lens. I’ve photographed camels before—on the dunes of the Gobi, the Sahara, and Egypt’s Western Desert—and each time, they strike me as grand, proud, tranquil beings.

Despite their grace, it’s my own kind, the herders who live among these creatures, who I’m here to learn more about.

Unlike most towns in India, Pushkar doesn’t have a railway station. To reach it, you have to take a jam-packed bus from the nearby city of Ajmer. For an hour, the bus rocks and rumbles down the dusty road before skidding to a halt at the edge of the town.

RELATED: Dancing for love in the deserts of Chad

Compared to other Rajasthani towns I’ve visited, Pushkar is quiet. I arrived a few days ago, on one of the last days of Diwali and a week before the official start of the famous Pushkar Camel Fair. As I walk around town on my first night, locals light candles along the edges of Pushkar Lake and the sky glows a deep pink. This sleepy town has already grabbed me by the eyeballs—and I haven’t even spied a camel yet.

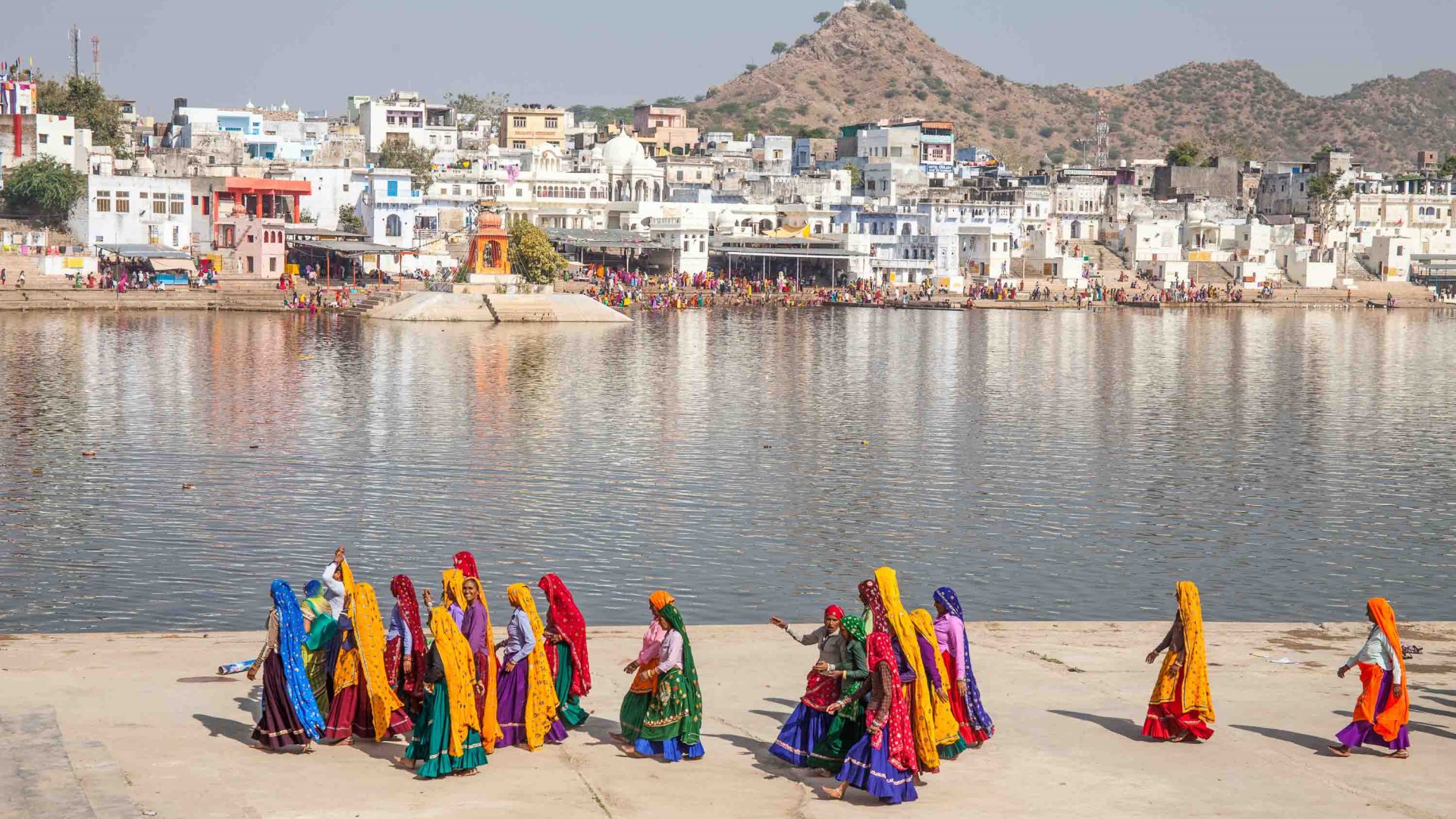

Pushkar lies in the west of India, between the sandy blankets of the Thar Desert and the technicolor cities of Rajasthan. It’s a small town, shrouded by spirituality—the lake in the center of town is said to have been formed by the tears of the Hindu God, Shiva. As such, it attracts pilgrims from all over India.

I meet Ram in a local chai (tea) shop in the early days of the fair. He’s a local musician, and the same age as me. I’m carrying a heavy, overpriced camera, but his instrument of choice is a piece of wood he’s carved into an ektaara—an Indian guitar.

Between sips of chai, he plucks it melodically, singing local folk songs about the harshness of the desert and family life. We become friends, and he introduces me to many of the herders and helps me gain their trust—enough for them to let me photograph their families (and their camels).

On our first morning together out on the dunes, a family of nomads invite us into their circle; the mother, who has a delicate face and bright green eyes, begins brewing chai masala spices with a bag of sweet milk.

The fair originally began as a way to attract camel and cattle traders to do business during the holy Kartik Purnima festival, traditionally held here on the full moon in the Hindu lunar month of Kartika (November-December). But inevitably, it’s now become a major drawcard for tourists, and the traditional camel trading has now given way to a program of activities—including camel beauty contests, camel racing and camel dancing competitions.

RELATED: Pakistan’s last Wakhi shepherdesses

The population of Pushkar, usually home to some 21,000 locals, booms to 400,000 during the festival. As the town fills with tourists and pilgrims, the official fair begins and a cultural program takes place alongside the camel market. There’s no shortage of activities and performances to behold—from temple dancing, folk music concerts, spiritual and heritage walks, and even a moustache competition.

While the weeks before the fair had been a serene affair, chaos sets in as soon as the official fair kicks off. Ram hates this part, and it doesn’t take me long to see why.

Tour groups arrive en masse, armed with zoom lenses, capturing the faces of the herders and their families without permission. I notice that many of the families I had spent time had left before the fair began, or were beginning to pack up early, fleeing the zoo-like pandemonium.

Away from the camel herding grounds, the cultural performances provide some alternative entertainment, and the women in their best clothes—bright colors, sequins, lavish fabrics—is a wonderful sight to capture.

The streets of this once-sleepy town are constantly congested and street performers from neighboring villages mark off street corners to charm snakes, play local music or perform circus tricks.

The calm of Pushkar is no longer, but I still find places of refuge—up Snake Mountain, which looms over the city, or out in Ram’s home village. Down at the lake, pilgrims are now visiting in their thousands, dipping into the holy waters.

As the fair eventually winds down, the remaining herders round up their camels and begin to march them over the desert back to their villages in the Western Thar Desert—and Pushkar returns to its usual sleepiness. With the madness over, Ram breathes a sigh of relief. Until next year, that is, when the surreal Pushkar Camel Fair will inevitably descend on the town again.

—-