In the heart of Lisbon, overlooking the lively Praça de Figueira, a hospital with a difference has been restoring dolls from Portgual—and the rest of the world—since 1830. Priyanka Sacheti pays a visit to this storied Portuguese institution.

“These are the plastic surgery rooms,” says Manuela Cutileiro of the two sunlit rooms overlooking the market square. A long table occupies each of them, with toy dolls in various states of dismemberment lying upon them, waiting to be brought to life again.

“We have a baby Jesus today, he came with a problem with his fingers,” Manuela continues. “The hospital happens to be a poly-trauma unit. We have five doll surgeons here, all of whom have received certification.”

It’s a warm Saturday afternoon and, outside, in Lisbon’s Praça de Figueira, the market is in full swing—overflowing with assorted goods from all over Portugal; a bevy of cheeses, wines, meats, pottery, and cork accessories. But here inside the Hospital de Bonecas (the doll hospital)—the world’s oldest—there’s little evidence of the commotion outside.

Saturday being a day when little work is done at the hospital, Manuela, the hospital’s owner, has time to show me around. Standing on the site of what was once the most important hospital in the city, All Saint’s Hospital—which was damaged and eventually demolished after a catastrophic earthquake in 1755—the doll hospital has been operational here since 1830.

RELATED: The families keeping a proud Rajasthani tradition alive

Before the doll hospital was the doll hospital, a woman by the name of Carlota da Silva Luz used to sit outside her shop in one of these buildings and make cloth dolls. The demand for simple repairs to dolls brought to Carlota by local children grew and grew—and the rest, as they say, is history. The hospital was founded by friends of Manuela’s family, and Manuela is the fourth generation of her family to have run the hospital.

A curious mixture of the absurd, enchanting and surreal, the hospital is many things: A hospital healing dolls, a magical toy-shop, and a museum containing numerous rare dolls. Far from being a relic of times past, the hospital’s services remain in high demand today. The waiting list for ‘surgery’ has been known to run up to four months.

The body part which requires the most repair is the eyes. Manuela opens a chocolate box-shaped container to reveal hundreds of blue glass eyeballs arranged into rows. As we walk through the hospital, cupboards with glass-fronted drawers reveal an eerie panoply of doll heads and parts; another room burgeons with faulty dolls and even more lost limbs—Manuela has collected them over the years. “Those are the donors,” she says of the hundreds of heads, legs, and arms.

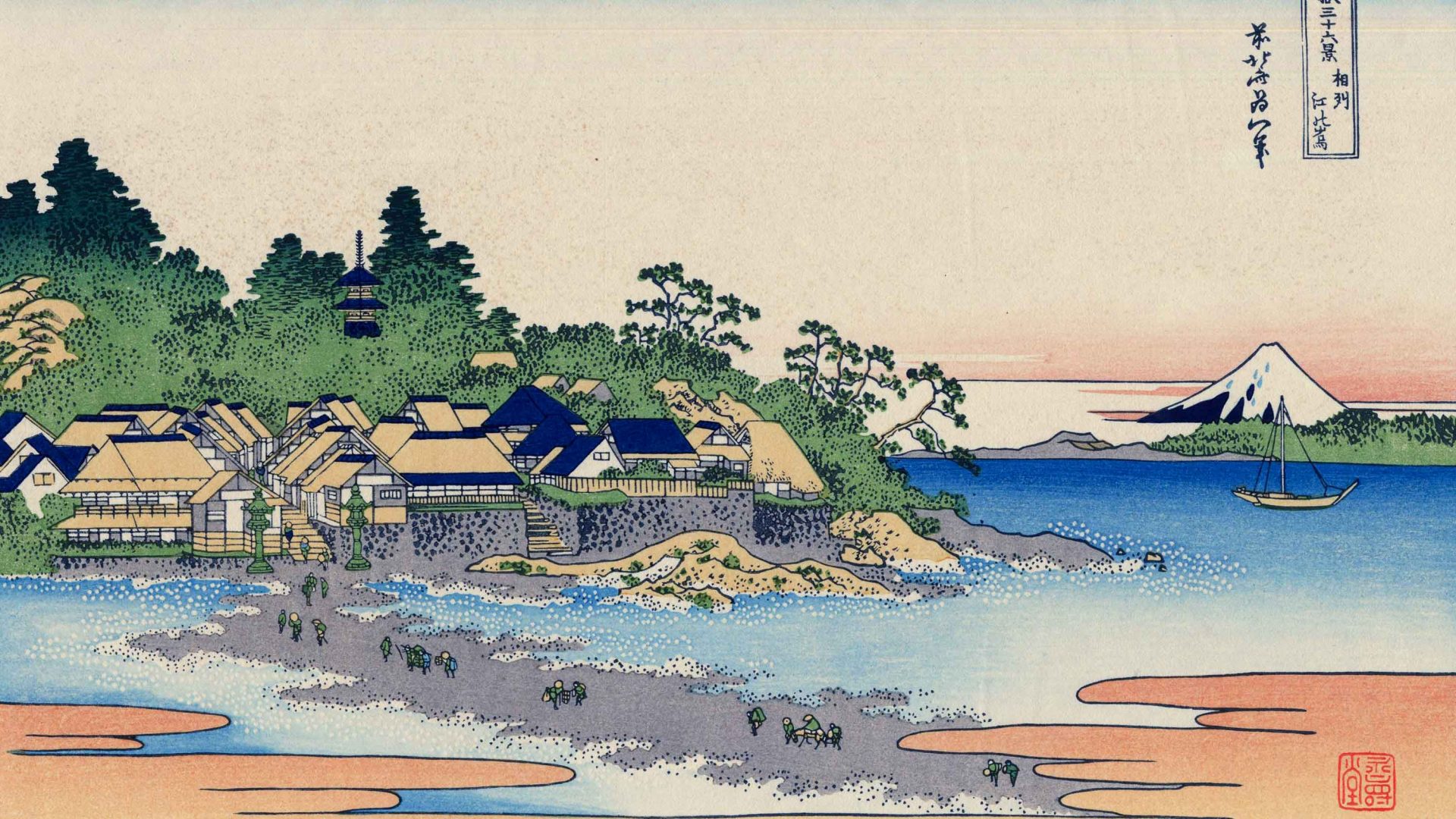

RELATED: The life and times of Japan’s most influential artist

For all the presence of dolls and their paraphernalia, including intricately constructed doll houses, it’s clear the hospital is not a space of play. I ask Manuela what she likes about working with dolls. “They’re like a different species,” she says. “They’re very easy to work with.”

Since some owners never return to collect their dolls, the doll hospital has amassed one of the world’s largest collections. One room is entirely dominated by a library of dolls, some over 100 years old, from as far afield as Germany, France, Spain, and Japan.

A petite, softly-spoken lady, Manuela emphasizes the fact that the doll hospital is more than just work for her. “It is my mission, really, a family mission,” she says with conviction, gazing at the silent, unblinking dolls gathered around her.

When it comes time to bid Manuela and her private universe of dolls farewell, I can’t help but ask. Does she think the dolls ever talk to each other at night? She doesn’t reply immediately, and takes a moment to consider my question.

“No, that only happens in the movies,” she says. “Here, the dolls are just dolls.”

––––