Many of the national parks are only accessible by sea, like Isla Magdalena’s penguin colony and little known Corcovado. Pali Aike, the volcanic national park that takes its name from the Tehuelche people, means desolate place, but it’s worth the journey, an archaeological site dating back thousands of years, according to Australis expedition leader Cristian Manca.

Manca explains the impact on the five original indigenous groups living on the archipelago. From the fierce Tehuelche to the Yaghan, these groups were decimated by disease, dispersal and the agriculture policies that came with the Europeans.

“Spotting the fires that local tribes had lit on some of the islands, Magellan’s crew were greeted by six-foot-tall natives, their feet wrapped in guanaco skins.” As Manca explains, Patagon (‘big foot’ in Spanish), and Tierra del Fuego (the land of fire) were unsurprisingly adopted as monikers for this southerly realm.

As the rewilding of Patagonia allows for the land to heal after centuries of gold prospectors and sheep farmers, it seems ironic that another wave of visitors might help to replenish the land through responsible travel, alongside CONAF’s [National Forest Corporation] careful management.

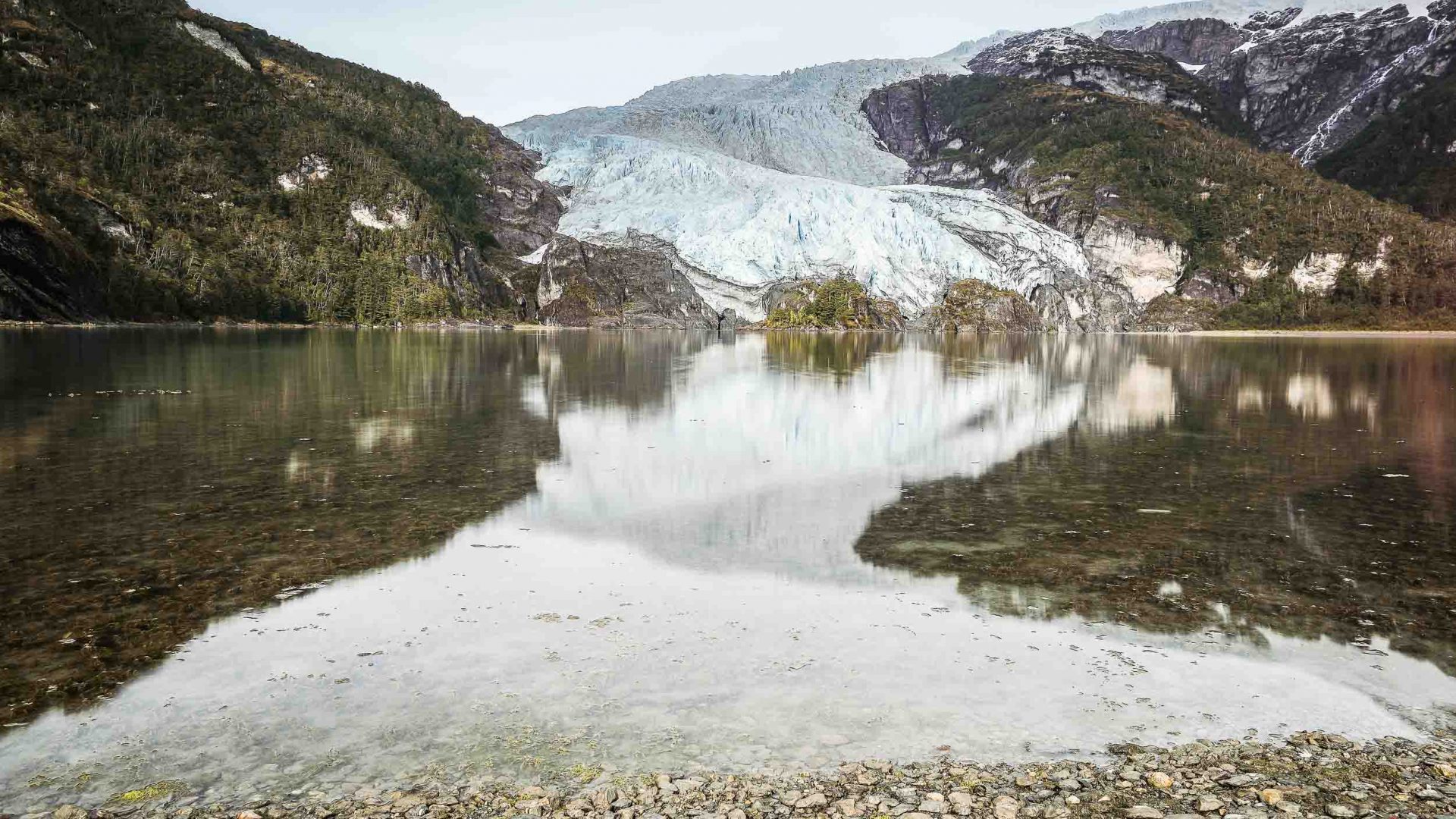

Sailors proverbially say that ‘below 40 degrees’ latitude, there is no law; below 50, there is no God’. But there, at 56 degrees south, I’m sure there’s something divine. I have yet to see Quelat’s hanging glacier, the fabled bay at Tortel and Corcovado National Park—and so many places on this vast route have not felt humanity’s footfall at all. Antarctica might be the earth’s last wilderness, but parts of Chile’s Ruta de los Parques come a very close second.