Editor’s note: This article was published before the coronavirus pandemic, and may not reflect the current situation on the ground.

Thanks to an intrepid group of Welsh explorers setting sail from their homeland in 1865, a small slice of Argentinean Patagonia will forever be Wales. John Malathronas investigates.

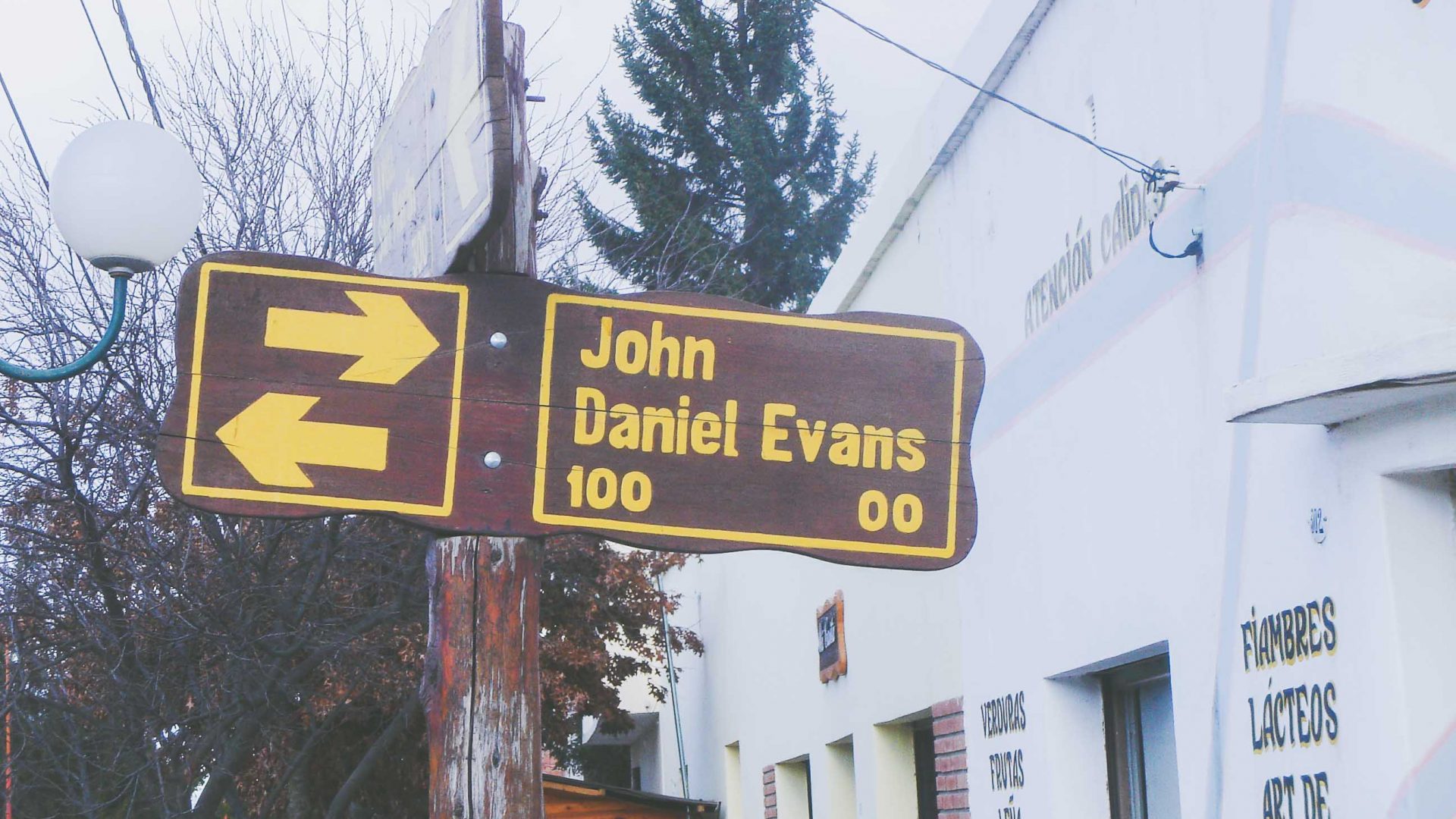

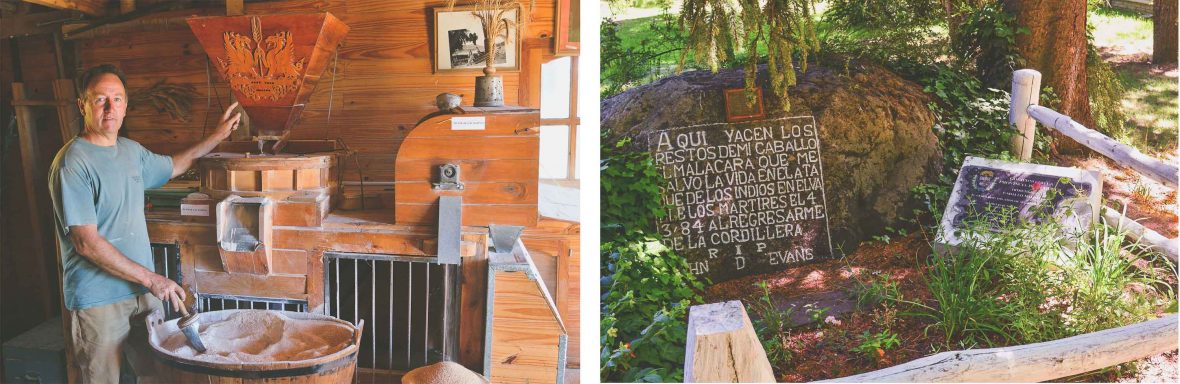

A sign in Spanish hangs on a Monterrey pine: “Malacara, let your memory live with my heirs”. Clery Evans—one of those heirs—points at a corralled grave, the focal point of a large, landscaped garden.

I look down and read: “Here lie the remains of my horse Malacara that saved my life during an Indian attack in the Valley of the Martyrs on 4-3-84 as I was returning from the cordillera.”

Yes, despite the presence of Monterrey pines, I’m not in California. Although I’m surrounded by a well-tended lawn, I’m nowhere near the home shires. I’m in the small town of Trevelin high up in the Argentine Andes and, well, this is the grave of a horse.

Trevelin is a town founded during a wave of Welsh immigration to Patagonia that started with the voyage of the Mimosa in May 1865. Those plucky Welsh pioneers wanted to establish a colony on a vast, almost empty tract of land that was remote enough to escape political control.

RELATED: Is Salta Argentina’s next adventure playground?

The nearest government was headquartered in Buenos Aires, hundreds of miles north, while despised Albion lay on the other side of the world—its small sheep colony of the Falklands opposite having been left to its own devices.

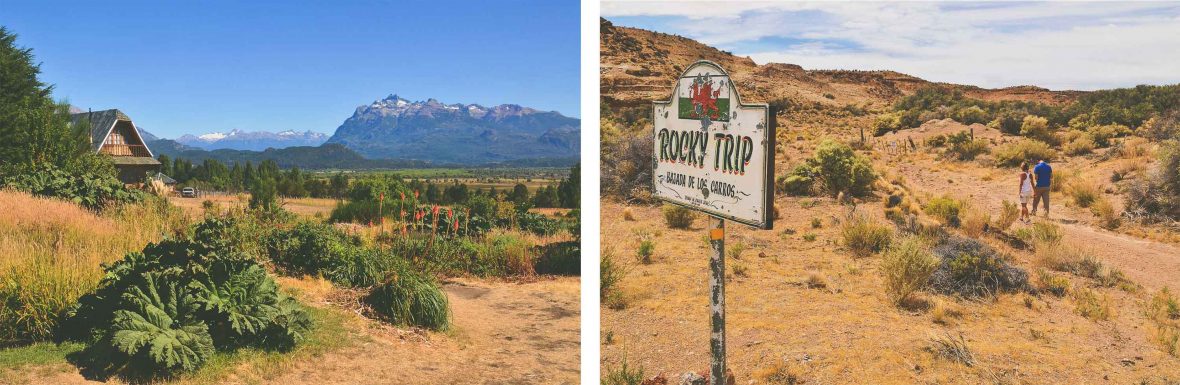

The main settlements were founded in the lower Chubut valley, a short distance inland from the coast: Trelew, Gaiman, Dolavon. Beyond those stretched the arid steppe; it took 20 years for the frequent search parties to discover a fertile valley—Cwm Hyfryd (‘Lovely Vale’)—some 400-odd miles west.

Evans was nicknamed El Molinero (‘The Miller’), after the flour mill he founded in Trevelin became a blueprint for the region. At its heyday, there were 22 mills in the area until the 1950s, when the newly-built Patagonian Express brought flour at lower prices from larger enterprises up north.

Today only Nant Fach remains, outside Trevelin, where Mervyn Evans, proud of his Welsh pedigree, single-handedly built a flour mill in his farm “so that the traditional knowledge is not lost”.

Welsh tradition is what travelers come to Trevelin for. They find it in abundance in the two casas de té: Nain Maggie and La Mutisia. With their maps of Wales, red dragon emblems and Welsh language posters, they serve afternoon tea and a bounty of cream cakes, baked “after grandmother’s recipes”.

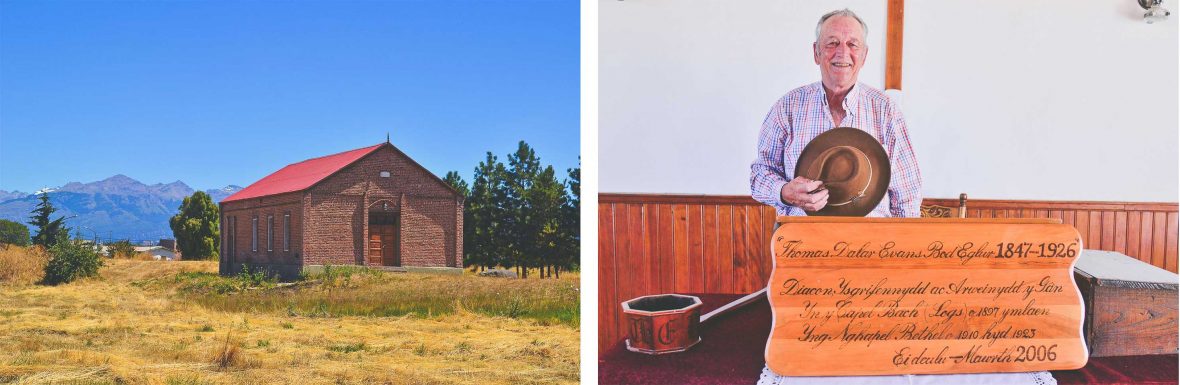

One thing Oscar’s kept, though, is his religion. He unlocks Bethel Chapel that stands on an open field with the Andes spectacularly silhouetted in the horizon. Non-denominational, it was first erected in 1897, but the current brick building with its red corrugated roof and hardwood floorboards dates from 1910.

RELATED: Inside Patagonia’s secret adventure town

“Here I baptized my children in 1970,” Oscar says. We used to have a wandering pastor who came for weddings and baptisms. We now open it for a reunion de canto—to sing hymns every now and again. There are always 60-70 people present.” The pastor’s lodgings today house ‘Ysgol Gymraeg Yr Andes’, a bilingual Spanish/Welsh school funded by the province of Chubut.

The Argentinians have a lot to thank the Trevelin colonists for. When Chile and Argentina divided Patagonia at the turn of the last century, they split the Andes according to its hydrography: The rivers flowing into the Pacific would belong to Chile and those flowing into the Atlantic would belong to Argentina. As Rio Futaleufú drains the region around Trevelin and eventually flows into the Pacific, this should all belong to Chile.