While the pandemic has seen many of us locked down, the natural world has been finding ways to recuperate—and sound tracker and acoustic ecologist, Gordon Hempton, can hear it happening. He talks to Kristin Kent about his quest to find and preserve the world’s quiet places.

Soundscapes by Gordon Hempton, the sound tracker

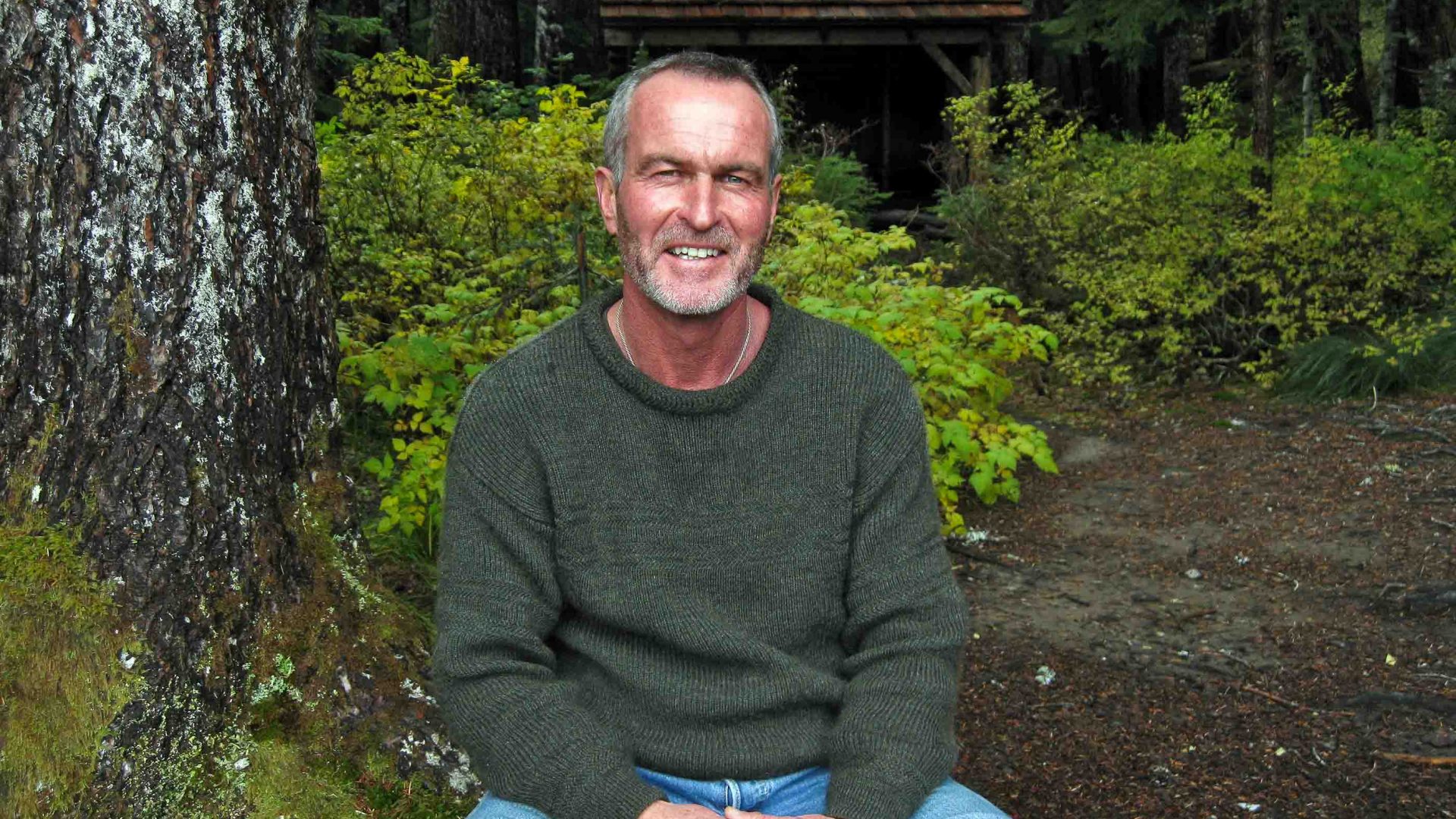

Acoustic ecologist Gordon Hempton is full of one-liners. That headline that caught your attention? That’s his. “Earth is a solar-powered jukebox.” Also his.

For over 30 years, Hempton has traveled the world in search of quiet. He’s recorded inside Sitka spruce logs, or ‘nature’s violin’, as he calls them. He’s recorded storms rushing the Kalahari Desert, and the moon setting across six continents. Hempton defines quiet as presence—not a lack of sound, but a lack of man-made noise. He believes silence is a part of our human nature; “a birthright”, he says.

From 2005 to 2018, Hempton campaigned to designate the Hoh Rain Forest of Olympic National Park in the United States an official quiet park, founding One Square Inch of Silence. His efforts garnered more than 300 million media impressions, but fell on deaf political ears. He has since shifted his focus with Quiet Parks International and has established the world’s first wilderness quiet park, in Zabalo, Ecuador. There are at least 262 more sites worldwide that Hempton would like to see certified and preserved.

When I first spoke with Hempton in February 2020—pre-pandemic—he was fresh from recording the vastness of the Haleakala crater in Hawaii, still buzzing from birdsong. I was eager to ask about the quietest places on earth—places I could go to escape the bustle. I did not expect air travel to come to a complete halt shortly after we spoke.