As one of the first tourists allowed to travel on an overnight sleeper through a remote part of North Korea, Allie Dunnington reports on how things have changed since she last visited a decade ago.

I don’t agree with boycotting countries. They never harm the regime, but hurt the people. That’s why I’m here, on Kim Jong Un’s ‘Orient Express’ in North Korea.

In this country led by a man who’s been accused of committing all but one of the 11 crimes against humanity, a country whose image is that of an evil, ruthless and unforgiving regime, I want to see for myself what life in the DPRK (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea) might be like. And what better way than traveling on a sedately moving North Korean train?

This journey will take me and my fellow travelers from the scenic eastern coastline northwards to the industrial city of Chongjin near the Russian border. We’re the first tourists ever allowed to travel on an overnight sleeper and to this remote part of North Korea. Carefully guarded by our two young North Korean guides, Mr Pak and Ms Kim, we’re given our first instructions: “You must always speak respectfully of our Dear Leader, Kim Jong Un. You can take photos while the train is moving, but please not in the stations. You must never walk alone. We are responsible for your safety and have to look after you”.

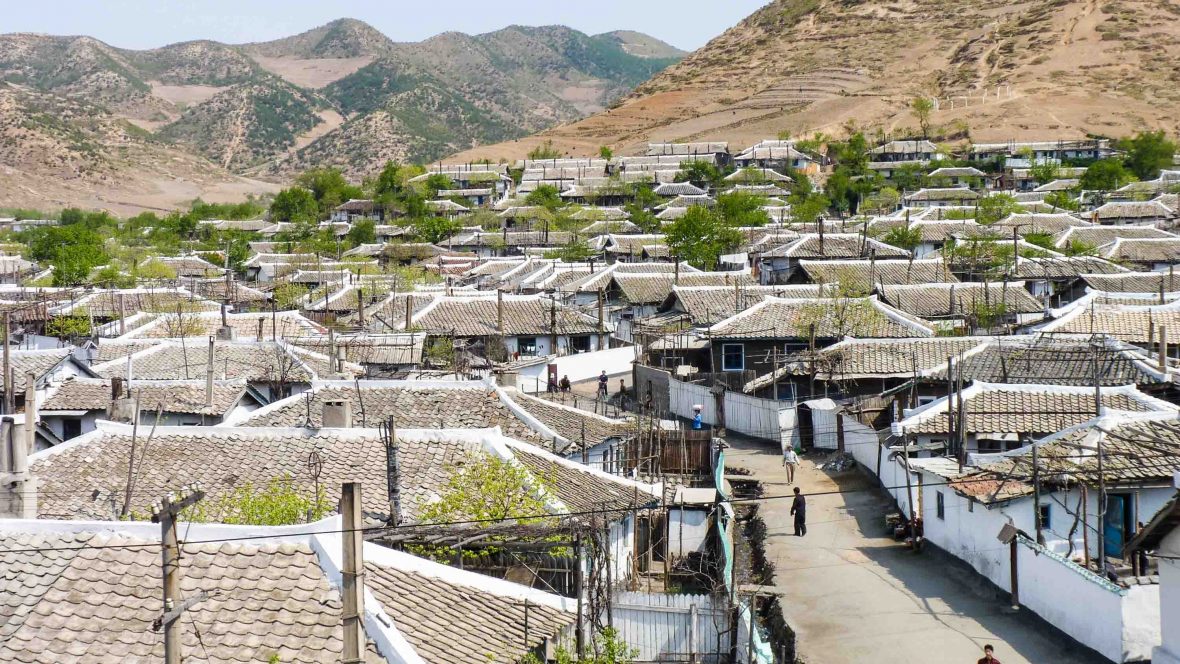

Pyongyang’s Central station. Everyone’s keen to get on board and settle into their compartments. There are four beds in each wagon and a dining car. As we leave the city, the landscape opens up to ploughed fields, small villages, rolling hills and pine trees.

RELATED: A stroll through the capital of Europe’s secret state

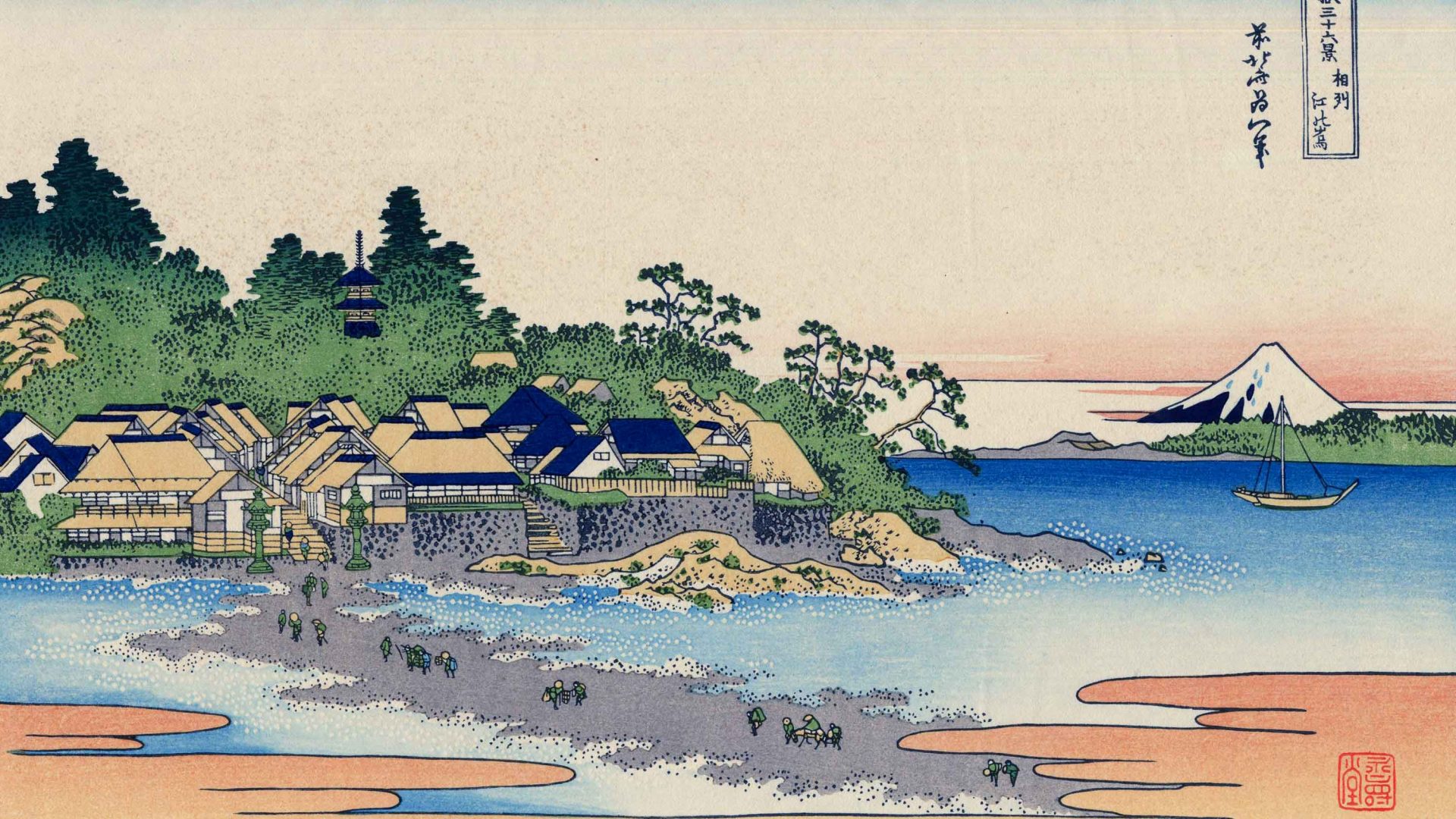

With the light spring drizzle, it’s like traveling through a Chinese water painting—one that’s occasionally interrupted by bright red revolutionary flags. In the fields and along the railway are oxen, and people are working with their bare hands. Most are walking. Cars are still a rarity. In the cities, bus queues are endless and many people drably dressed. Shops are infrequent and often bare.

Sheepishly I dare to pull out my camera, open the windows and take a couple of hasty shots of kids excitedly waving at us.

The next morning, we step outside to a view of the sea and tiny islands. Once an important trade port with daily ferries to Japan, a turbulent, violent past has stopped most of Wonsan’s international exchange: “We were invaded by the Mongolians, Jurchens and Chinese,” explains Ms Kim, “then the Japanese took over from 1910-1945. After this, the Imperialists [she means America] wanted to take our country. But our revolutionary army under the great leadership of our President Kim Il Sung defended our nation.”

An armistice was signed on July 27th 1953 between the DPRK, the UN South and North Korea, but after 65 years, there’s still no formal peace treaty. The Kims always had their country under tight control: Rights such as ‘freedom of speech or movement‘ may be in the constitution, but they don’t de facto exist.

It’s the government who decides what’s allowed or not, down to hairstyles. Any wrong-doing and you could end up in a prison or endure a lifetime of forced labor—and this can affect the wider family. Those who safely leave for China or South Korea continue to worry for families and friends who may be punished instead.

Next stop: Hamhung on the north-eastern coast. It’s a lesson in chemistry while holding our breaths, thanks to the noxious smell in one of the DPRK’s largest fertilizer plants, followed by a refreshing if freezing-cold swim in Korea’s East Sea and an unexpected clam barbecue beach party with our guides.

It’s welcome respite before a long stint on the train the next day. Soon, we are only 200 kilometers from the Russian border. Mr Pak puts on a stern face: “We are now entering Chongjin,” he tells us. “It is the third-largest city and was the main industrial hub for iron and steel production. We have worked very hard to get permission for you to visit, so please stick to our rules!”

I feel his concern and worry. Misbehavior reflects badly on guides and tour operators: there may be an inquiry, penalties or, worst-case scenario, accusations of being ‘Western collaborators’. With tourism in its infancy, visitors are even asked to sign a form that we will comply with the rules.

It’s a tight schedule in Chongjin, which includes a ‘foodstuffs’ factory, a massive statue of Kim Il Sung, the first Supreme Leader of North Korea, a modern ‘e-library’, the Chongjin revolutionary museum and a musical performance by the Chongjin ‘Steelworks kindergarten’ where kids sing and dance in perfect synchronization with slightly disconcerting doll-like smiles.

RELATED: Iran, one of 2018’s most underrated destinations

Soon, it’s time to socialize with the locals at the Seaman’s Club. The pub is empty. Has everybody gone home already? It’s only 6 o’clock. Slightly disappointed about not really meeting the locals, we return to our hotel. This is a country deeply stuck in a myriad of hidden rules, regulations and repressions; spontaneously mixing with locals in some areas may be years away.