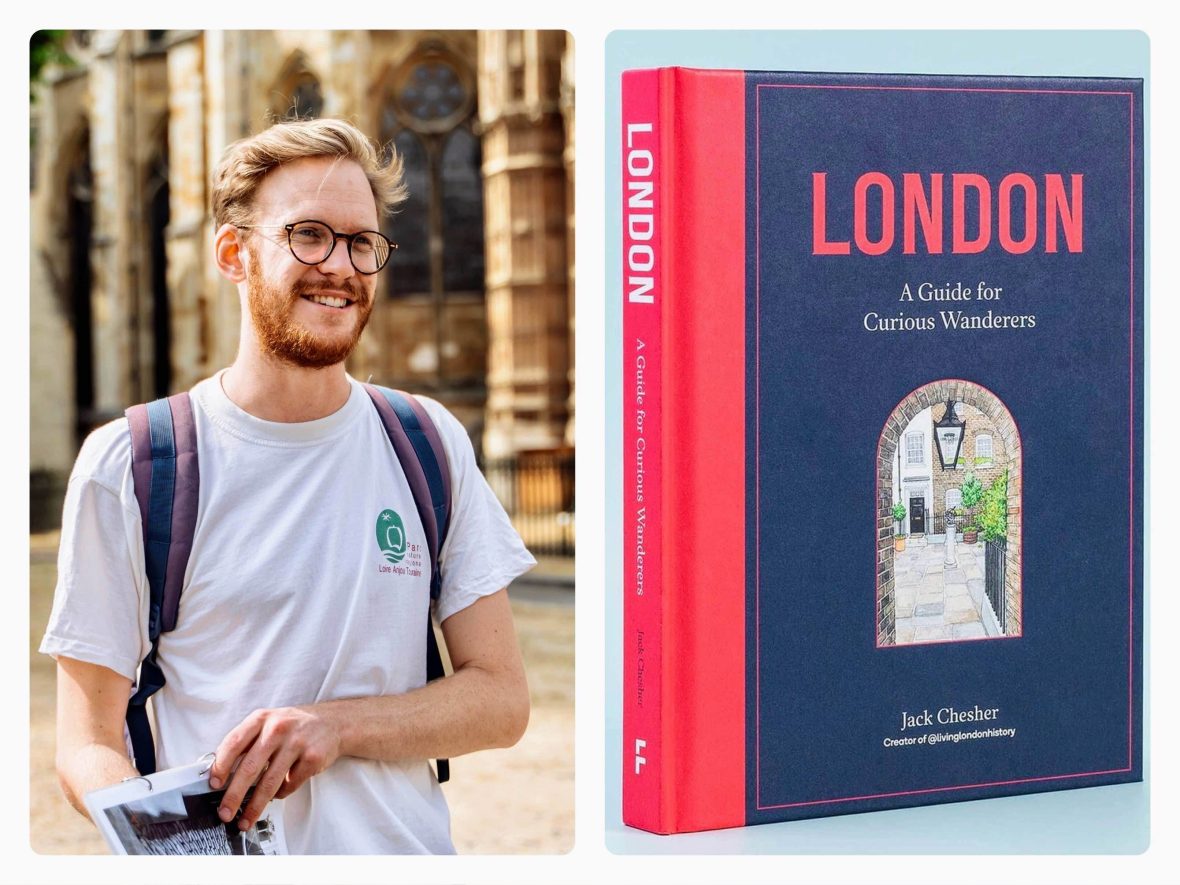

Your city is hiding countless secrets, right there in plain sight. You just have to open your eyes, says Jack Chesher, author of London: A Guide for Curious Wanderers.

Your city is hiding countless secrets, right there in plain sight. You just have to open your eyes, says Jack Chesher, author of London: A Guide for Curious Wanderers.

If you like walking around and discovering weird bits of history right under your feet, it might be hard to find a better city than London. All across the metropolis, you’ll find fascinating stories hiding in plain sight. All those classic red mailboxes, for example, are decorated with the initials of whoever was king or queen at the time the box was made, which indicates how long it’s been there. Many of the planters on the sidewalks look like cow troughs because they are cow troughs, installed at a time when livestock was marched from farms as far away as Scotland straight into the city.

I learned this from Jack Chesher, author of London: A Guide for Curious Wanderers, and creator behind the Instagram account @livinglondonhistory. We met recently at Smithfield Market, where vendors have hawked meat, livestock, and unwanted wives (divorce was hard in the Victorian times) for nearly a thousand years.

Chesher took me on a mini walking tour of the area, pointing out sites of legend and lore in the 900-year-old St. Bartholomew’s Church and elsewhere around the Borough of Islington. But what I really wanted to know was his secret to staying in the present.

In a world where we’re always looking at devices in the palms of our hands, how can we be more observant travelers—both abroad and at home?

How can we pay better attention to what’s going on around us?

We always spend a lot of our time these days looking down, not being aware of our surroundings, particularly in a busy city. So if you’re out and about, be as observant and curious as possible. Generally, in London, when you’re on your way to work, it can be very busy.

Obviously, you don’t want to be constantly stopping on the pavement, but give yourself a bit more time and get off your normal routes. People always get stuck in finding what is ultimately the quickest route to work, or the quickest route to the Pret for lunch. But if you take a different turn, or go down a little lane or alleyway, you’ll start to build up a bigger picture. You’ll be surprised about how much you’ll find. Looking up more often gets you to see these details above façades and above the eye line.

When I first started properly exploring, if I was getting the Tube, I’d get off a stop or two early. This way, you’re not popping out of the Tube two minutes from where you’re meant to be. Even if you get off one stop early, you’ll see way more.

Postman’s Park, for example, has the Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice. It’s got 54 tablets dedicated to people who died while trying to save the life of someone else. Some of them are very dramatic… There was a pantomime artist who tried to put out a fire in a theater with her dress, and went up in flames.

What are some other examples of history hiding in plain sight in London?

The Strand, for example, where I run one of my tours, is a road that most people who are on the tour have walked. But if you take the time to stop and look, you realize how much there is that you are missing when you’re whizzing along in your own little bubble. For example, I talk about the sculptures on Zimbabwe House. They’re called Ages of Man, by Jacob Epstein, and when they were put up, they caused a bit of a stir in prudish Edwardian society because they were of naked figures. The press were in uproar, and the police and church inspected them. In the 1930s, they started to be degraded by acid rain, so in the end it was decided to lop off all the extraneous limbs/appendages, so today they appear to be mutilated. They’re a great example of why it’s good to look up in London.

Another one is a unique lamp on Carting Lane, just off The Strand. It’s one you’d probably walk straight past, but it’s the only one left in London. When the new sewer system was put into London in the Victorian period, one of the initial issues was the potentially explosive build-up of methane gas in the sewers. One solution was invented by a man called Joseph Webb: The sewer gas destructor lamp. The flame of the gas lamp runs off the normal gas supply, and draws up the gases from the sewer through a hollow lamp post and burns them off. It is affectionately known as ‘the fart lamp’…

“I went to Paris at the beginning of this year, and bought a guidebook about ‘secret’ Paris. I found the oldest tree in Paris, and the oldest street sign. These days, I spend a lot more time looking down little alleyways.”

I used to live in a busy part of London where I could see into a train station from my living room. At first I felt exposed, but then I realized no-one—no-one—ever looked up.

Yeah, it’s a shame—there’s so much that people are missing. Lots of my tours aren’t even off-the-beaten-track areas. In Islington, for example, there’s a street called Middleton Passage. It looks normal at first, but further up, the bricks are carved with numbers and initials. It was a complete mystery for ages. People thought the wall was made by Napoleonic prisoners, and that they carved their prisoner numbers into the bricks. But more recently, a historian looked into it and found out that they were police registration numbers. In the early 1800s, this was a notoriously dodgy street, and bored policemen would carve their registration number, so it’s police graffiti. They were supposed to be out here solving crime, and instead they were sort-of committing crime…

When I first started finding these places, I made a big Google Map and pinned loads of stuff. So if I was reading something and found a hidden detail or something you could go and see, I’d mark it on my map. Then, if I had a spare afternoon, I’d look at one area and go see five or six places I’d pinned. It’s quite an efficient way of doing it.

What are some other research methods people can use to get to know their own cities better?

Nearly everywhere will have a local bookshop with a local interest section. That’s a pretty good place to start, because there’s always going to have been someone interested in the history of your area and written about it. Or you can look for a local history society to see old photographs, for example. Then there’s social media: In London, there’s probably way more people posting about it than in a smaller town, but I know there’s a guy who does something similar in Melbourne.

Do you explore the same way when you’re abroad, too?

More so now that I’m doing it with London. Previously, I’d have gone on a walking tour and maybe gone to a museum, but not necessarily sought out those quirkier details.

But now, for example, I went to Paris at the beginning of this year, and bought a guidebook about ‘secret’ Paris. I found the oldest tree in Paris, and the oldest street sign. These days, I spend a lot more time looking down little alleyways. I dragged my partner on an ‘alleyways of Paris’ walk, peering down private driveways that were listed in my guidebook.

Where would you recommend visitors go in London, to see beyond the standard sights like Big Ben?

There is a lot in the City of London [the historic financial district]. People do the Tower of London and St. Paul’s Cathedral, but there’s so much more in the area, and often Londoner’s don’t go either. They think, “Oh, it’s the financial district, I don’t like that.”

But there’s the Guildhall, and while you can’t go inside it, there’s the beautiful Guildhall Art Gallery right there, with the old Roman amphitheater in the basement, which is well worth it. There’s All Hallows by the Tower, a really interesting church with a crypt museum. They’ve got an exposed bit of Roman pavement, a model of Roman London, and various Saxon, Roman, and Norman artifacts. You can literally almost see the layers of history going up through the crypt. And both of these are free.

St. Bride’s, just off Fleet Street, is one of the oldest churches in London and has a great museum. The Charterhouse is also an interesting museum. It started on the edge of a plague pit, then became a Carthusian monastery, later turned into an almshouse, then a Tudor mansion. Not many people have heard of it.

If you’re interested in literature, you might want to go to the Charles Dickens House, or the Samuel Johnson House. I always recommend churches, gardens, and pubs—they’re all free, at least to enter.

Do you see your hometown differently now, too, through this historic lens?

I’m trying to pay more attention now. I’ve walked down the high street so many times in my life in Leigh-on-Sea {Essex], but I’m trying to be more observant. Like, oh God, why have I never spotted that? Or why did I never go into this really old church in the village? Churches can be amazing receptacles of history and are usually the oldest building in the town or village.

There’s one my friend told me about recently, outside the town I grew up in. There’s a grave outside the church and it has these big grooves on the top of it. It’s probably an urban myth, but it’s still a fun story—they say it’s because of the press gangs who’d wait outside church after a Sunday service and sharpen their knives on top of this gravestone. Then they’d grab people to press gang into the Navy, or whatever they were doing. And then, because of that, I noticed another grave that said the woman died at the age of 130. It’s probably not true—she probably, obviously, didn’t die at 130. But I’d never spotted that before…

***

Adventure.com strives to be a low-emissions travel publication. We are powered by, but editorially independent of, Intrepid Travel, the world’s largest travel B Corp, who help ensure Adventure.com maintains high standards of sustainability in our work and activities. You can visit our sustainability page or read our Contributor Impact Guidelines for more information.

Kassondra Cloos is a travel journalist from Rhode Island living in London, and Adventure.com's news and gear writer. Her work focuses on slow travel, urban outdoor spaces and human-powered adventure. She has written about kayaking across Scotland, dog sledding in Sweden and road tripping around Mexico. Her latest work appears in The Guardian, Backpacker and Outside, and she is currently section-hiking the 2,795-mile England Coast Path.

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: