Jungle, a new film starring Daniel Radcliffe, recounts the true, near-death experience of a traveler lost in the Amazon. But now, the indigenous community that saved him faces a danger of its own.

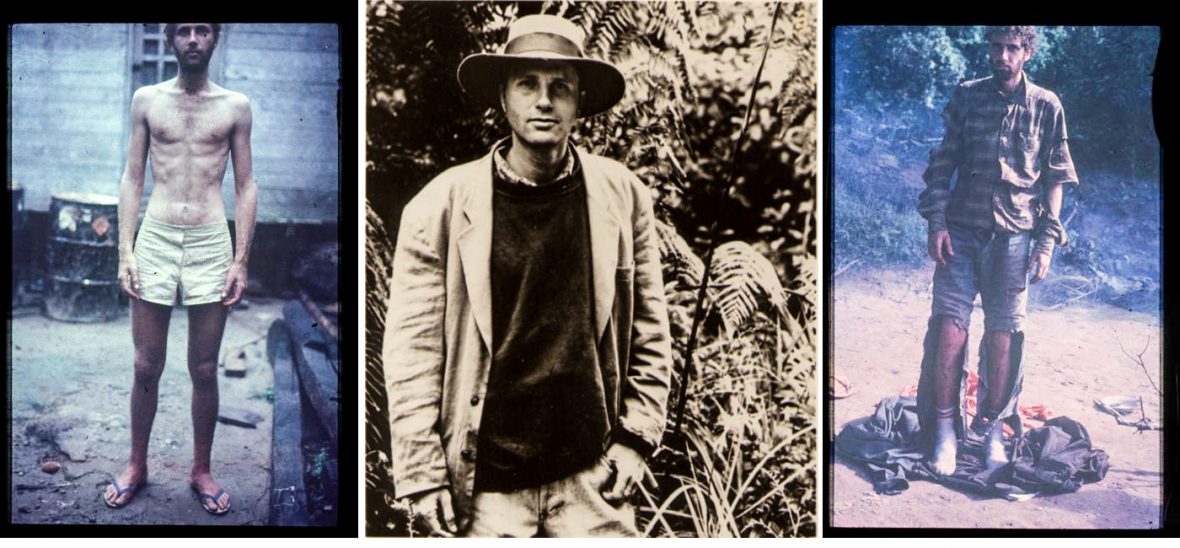

“I want to eat,” Yossi Ghinsberg pleaded with the man who came to his rescue on a boat. “It doesn’t matter if I die, but I have to eat … ” The starving Israeli adventurer had lasted 21 days, lost in the Amazon rainforest, wondering when he would find food.

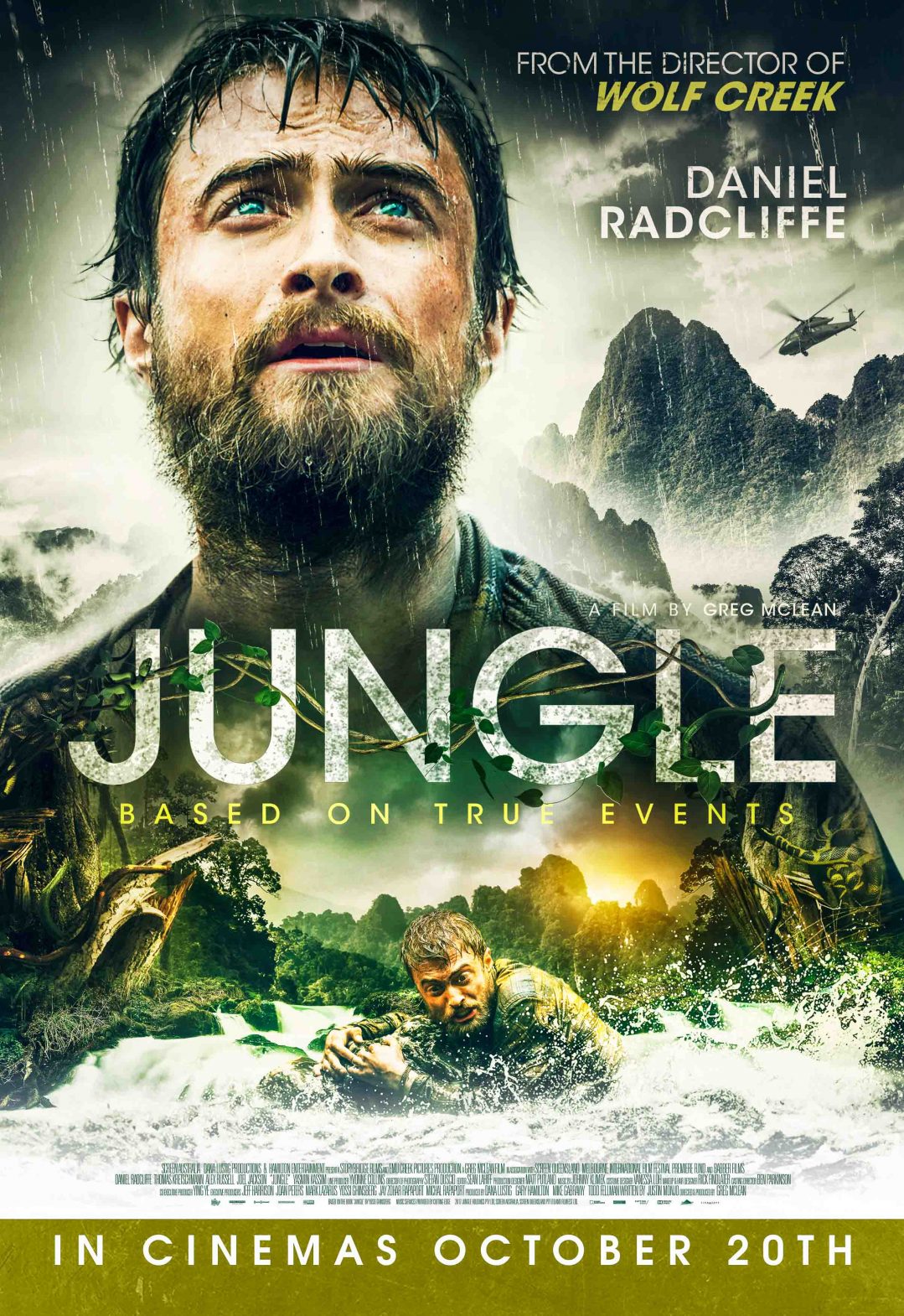

On October 20, 2017, movie-goers can see this real-life ordeal played out in Jungle where Daniel Radcliffe [of Harry Potter fame] plays Ghinsberg as he fights for his life in the Bolivian jungle. The backpacker had become separated from his companions and survived for three weeks before being rescued by one of his party—who launched a search mission—and locals from a nearby village.