Editor’s note: This article was published before the coronavirus pandemic, and may not reflect the current situation on the ground.

On the outskirts of a lesser-known central Iranian town, a natural marvel hides an ancient, mythological secret. Marco Ferrarese goes digging for clues.

Breathing

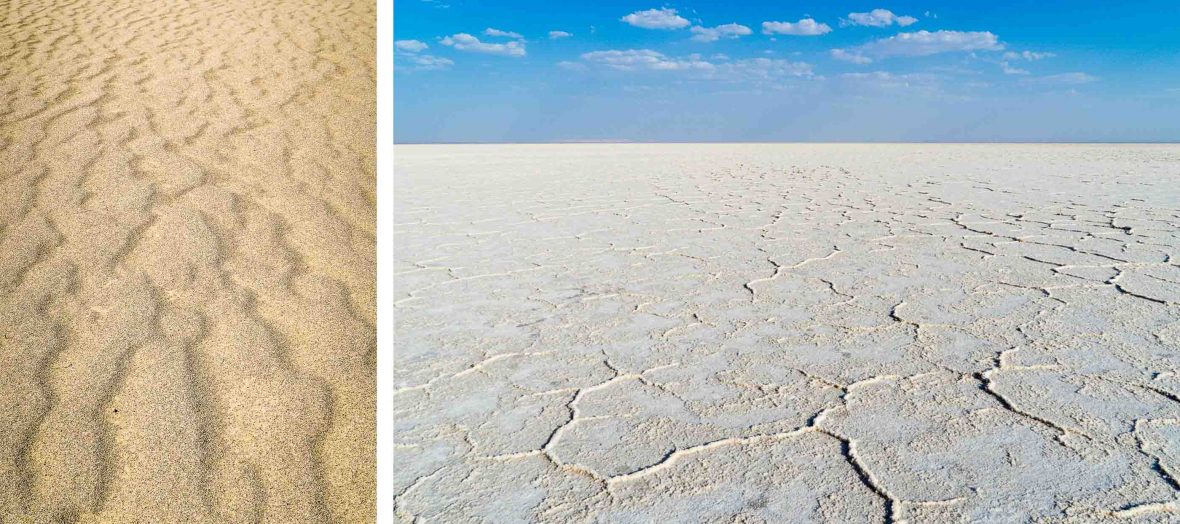

heavily, I set one foot in front of the other, dunking my heels into soft, cold

sand. Above me, like a powerful light bulb hanging from the sky, the early

spring sun reflects over 360 degrees of silent dunes.

The

going is solitary and tough, but the sand breaks under my steps and supports me

like a ladder, giving me the balance I need to keep climbing. I am resolute,

and curious to see if this really is

the marvel that buried an ancient civilization.

When

I finally reach the top of the dune, pearls of cold sweat run down my spine and

my vision blurs. I need to sit down and rest. Slowly, my eyes readjust to a new

world of shimmering, undulating ochre sand, beautifully arranged before me as

far as I can see.

“Legend says that once upon a time, there was an ancient town where you see the sand dunes today,” my host Sina tells me. He sits before me, cross-legged, and holding a cup of aromatic tea in his right hand. His glasses fog each time he takes a sip.

RELATED: The Iranian youth hitchhiking their way to freedom

This young man, whom I’m sat next to on a compressed-cotton mattress, is the shaggy-haired owner of Negar guest house. A dry, star-shaped fountain stands before us, marking the center of this traditional Iranian courtyard. The pallid sun sends some feeble early spring warmth our way. I’d met Sina serendipitously on Couchsurfing.com, after I posted an open request for hospitality in the well-known central Iranian city of Esfahan.

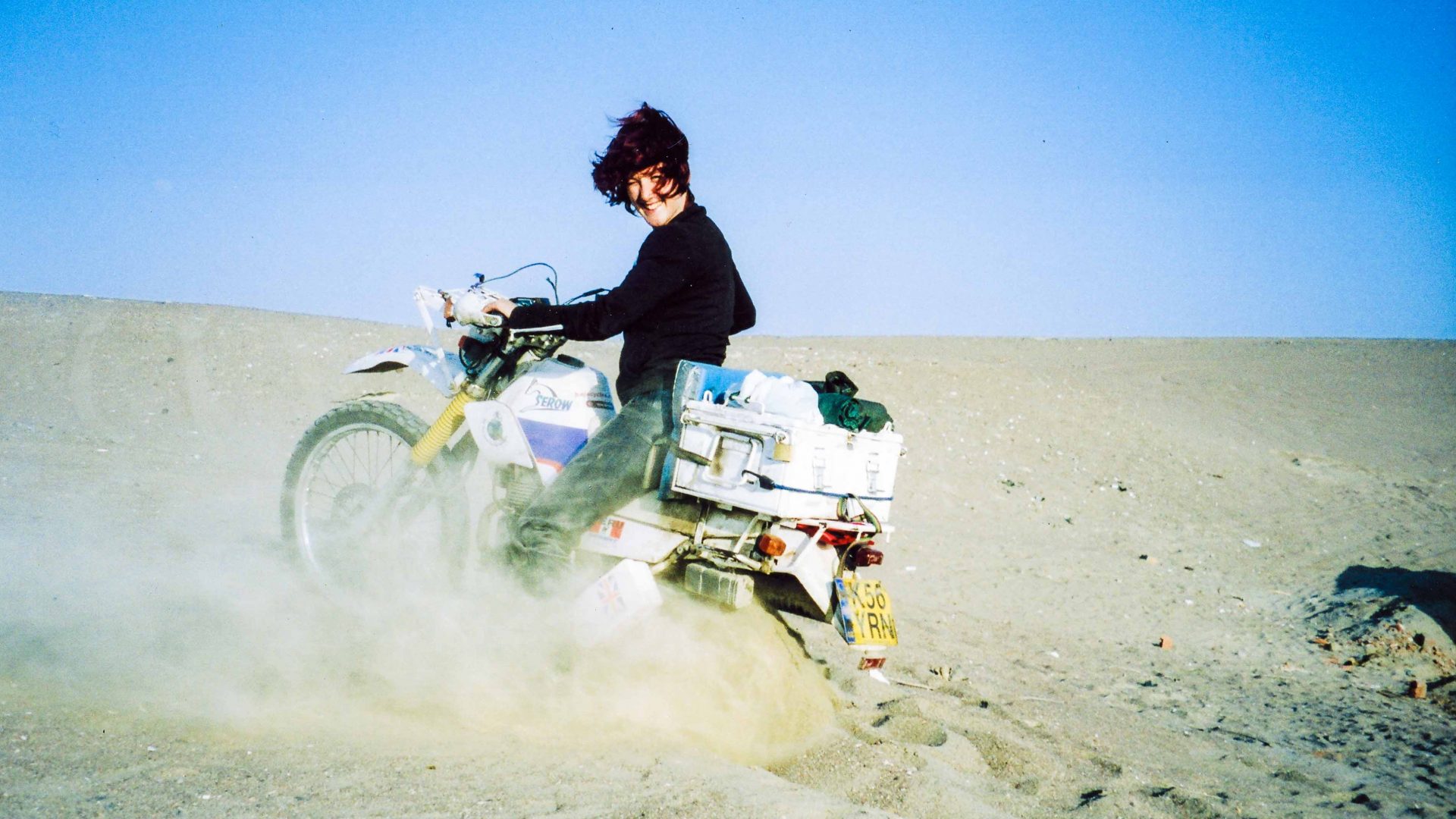

“You should come to my village instead,” Sina wrote back, extending an invitation to say in Varzaneh. I had never heard of this tiny dot on the map before. Only 105 kilometers southwest of Esfahan, Varzaneh is on the way to the barren expanses of the Dasht-e-Lut, Iran’s great southeastern desert. “You can stay in my guesthouse free of charge. We have giant sand dunes you can explore. It’s like the Sahara, but without the tourists and the hassle,” continued Sina. Even though we’d never met, he knew what I was looking for.

“A long time ago, a father fell in love with his own daughter and decided to marry her,” he says between sips of his tea. “He was so mad about her that he went on to ask permission of the whole village, persuading them until they all agreed to his sinful proposition. This infuriated the gods, who sent a violent sandstorm from the sky and buried them all alive.”

Believe it or not, the story of that sinful civilization starts ringing truer once I reach the top of the dune, sit down, and look around and beyond the limits of nearby Varzaneh, only a couple of kilometers behind me.

Like the barren distance between here and Esfahan, Varzaneh is surrounded by rocky land strewn with dry bushes, an environment that seems unlikely to ripple into mountains of sand. “Archaeologists have even found ancient pots and earthenware while digging around the dunes,” Sina says in support of his supernatural hypothesis.

I start believing the legend more and more as I discover the Gavkhooni wetland. This preserved ecosystem, about 25 kilometers from the dunes, hosts hundreds of migratory birds and a salt lake under the watchful eye of magma-born Black Mountain. I am confused: Sand dunes fallen from the sky, or a natural oasis cast in the middle of a rocky desert?

RELATED: Is Iran one of the world’s most underrated destinations?

Regardless of whether or not the tales of the immoral community who may have once lived here are actually true, modern-day Varzaneh couldn’t be less immoral if it tried. At the heart of this quiet gem of maze-like alleys is a simple, central mosque. And it may be because I’m in town on a Friday, but the place is swarming with faithful residents, going in and out for their prayers.

The women are wrapped in white, ankle-length chadors (open cloaks that leave the face exposed). Like stains of purity dropped over Varzaneh’s ancient fabric of (alleged) sin, the women spill out of the mosque like doves, and fly low and away to their homes, across the brick-gray alleys. I follow them from afar until I reach the river side and see them cross the arches of Varzaneh’s ancient bridge. So silent and discreet, these faithful people seem so much the opposite of the lustful town described in the legend.

I return to Negar guesthouse as the sun goes down. Sina is seated on the floor, busy fiddling with his laptop. “I am writing up a Workaway description to get more volunteers here and run the guesthouse even better,” he says, without lifting his gaze from the screen.

He reminds me of how this former Iranian Sodom is catching up with the modern world. Outside, vans filled with Iranian tourists shuttle back to their cities. They come here to slide down the closest sand dune, which is already managed by an enterprising local who’s set up sand-boarding and jeep joy rides. Foreigners, like me, will certainly start coming next.

Despite Varzaneh’s advances towards a tourist-friendly future, I can’t help but wonder: If the residents of present-day Varzaneh keep trading the luxury of flesh for the quick gains of tourism, what will the gods throw over this town next?