In Kenya, a drought has rendered many local farmers desperate for income and sustenance. Instead of poaching, bees are providing a sweet—and sustainable—saving grace.

How bees became a former poacher’s saving grace in Kenya

On a sticky night in 2019, Yusuf Bonaya crouched silently behind a tinder-dry thicket of spiky myrrh bushes. A few meters away, an exhausted dik-dik—a small antelope—struggled weakly in the snare. Bonaya wanted to free the panicked animal, but it would have to wait a little longer. He had a predator to catch.

That morning, while patrolling the 45-kilometer-long electric fence that separates the Mbulia Conservancy in south Kenya from Tsavo West National Park, one of Yusuf’s team had spotted human footprints in the paprika-colored dirt.

“We knew they were made by a poacher,” shouts head ranger Bonaya over his shoulder as the open-sided safari car rumbles along the rutted track, a curtain of orange dust unfolding in our wake. “So we followed them. When we found the snare, we decided to set up an ambush.”

That’s how he caught David Mwakesi, 48, a local farmer and small-time game poacher, as he returned to collect his terrified dinner. But instead of handing him over to Kenya Wildlife Services for prosecution and a stint behind bars, Bonaya did something unexpected. He gave Mwakesi a stern warning, and then asked if he’d like to quit poaching and become a beekeeper instead.

“Guys like David aren’t criminals,” Bonaya explains. “They’re just desperate. If he’d had five or six dik-diks I’d have had to arrest him, but with only one… that’s just a man who’s struggling to survive. So we try to help.”

Poaching is an ongoing problem in Kenya. While a controversial ‘shoot-to-kill’ policy introduced in 2018 has gone some way to deterring criminal gangs targeting rhinos and elephants, an 18-month-long drought in the Tsavo region devastated crops and forced some farmers into hunting bushmeat simply to feed their families this year. Every month, Bonaya and his team of rangers find and destroy as many as 170 snares on their patrols around the Mbulia Conservancy.

Beekeeping has another surprising benefit: It’s saving elephants’ lives. That’s because the elephant, the largest land animal, is terrified of the humble bee, one of the smallest.

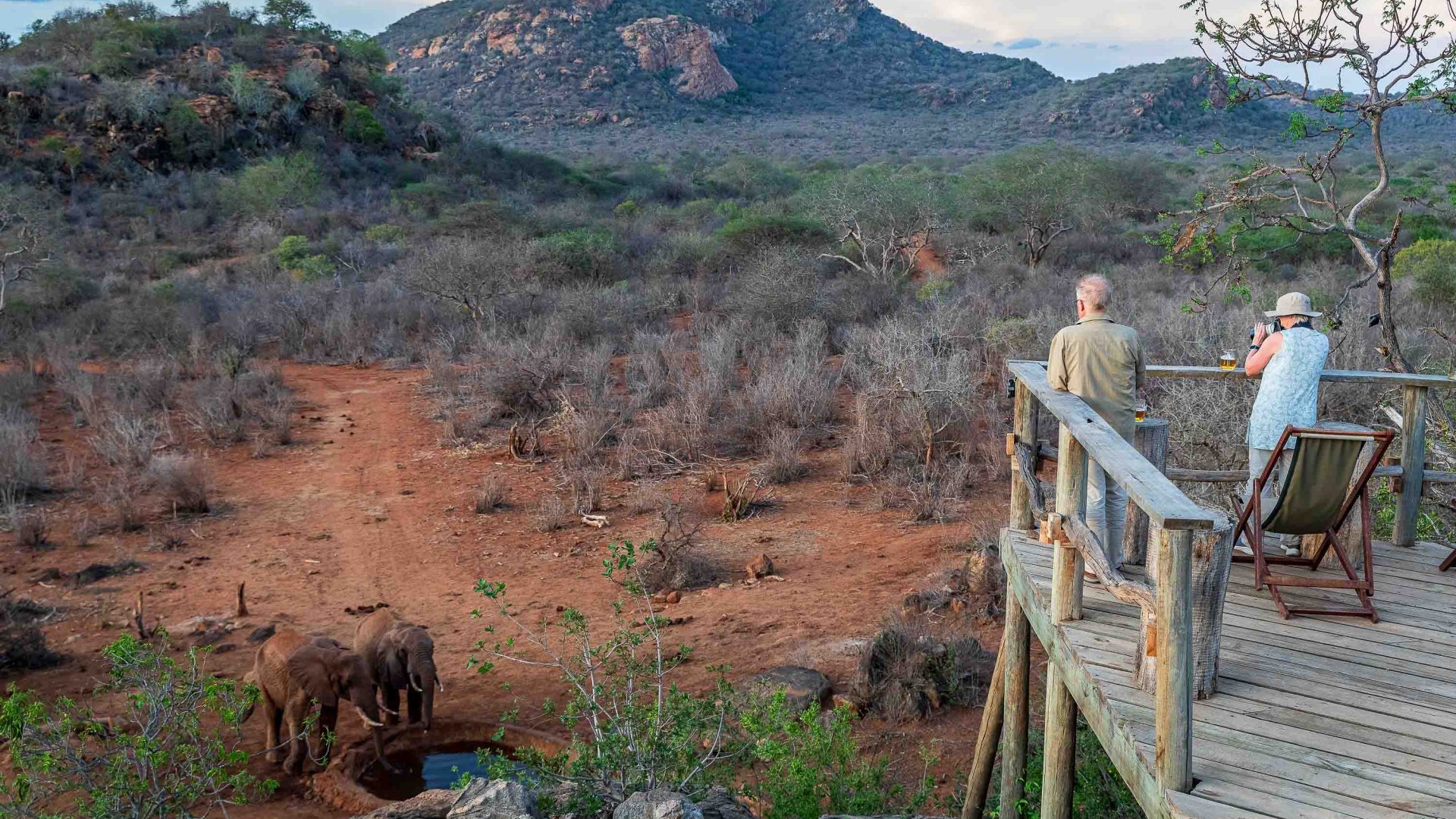

Covering 15,000 hectares, this community-managed wildlife reserve was established in 2012 by Kenyan-born Richard Corcoran, the managing director of Secluded Africa, which runs four luxury lodges in Kenya.

“This was basically wild land with a small farming community of about 4,000 people living on it,” he tells me, as we sip tea in the shady dining area at Kipalo Hills, the company’s Tsavo lodge. “Human-animal conflict was a huge problem. Elephants raided the crops, the farmers would try to drive them away, then an elephant would kill someone, so the people would poison the elephants. Everyone lost.”

To reduce the conflict and protect the wildlife, Corcoran built a fence around the conservancy and set up the ranger unit to manage it. Guests who stay in the company’s lodges pay a US$60 per day conservation fee to the Secluded Africa Wildlife and Community Trust, which funds the rangers, as well as a host of other community projects including daily refilling of the waterholes, planting trees, supporting more than 60 of the poorest local children through school, emergency food drives and medical care, and training adults in skills like sewing, mechanics and beekeeping.

Today, Bonaya is taking me to meet Mwakesi, one of their more recent success stories. As our car bounces along the uneven trail, the shadow of the ongoing drought looms large: We pass parched waterholes, the mud where elephants and buffalo once wallowed now brittle and cracked like oak tree bark, and skeletal bushes, their branches leafless and bleached by the relentless sun.

We pull up outside a barren smallholding surrounded by a tangled thorn-branch fence, in the middle of which squats a single-story shack built from mismatched wooden poles, sheets of rusty corrugated steel and patches of recycled tent canvas. In front of it, a cayenne-colored field is pockmarked in neat rows where Mwakesi has planted maize and corn in desperate hope that rain will soon water it. But, right now, nothing is growing.

The poacher-turned-beekeeper is a slim man in his late 40s wearing a creased green cotton shirt, red trousers, and a faded New York baseball cap. He leads me to the perimeter fence, where a few spindly trees are hung with wooden cylinders, each about a meter long, dangling still in the breezeless air.

“These are traditional log beehives,” Bonaya translates from Swahili. “He has 13.”

Mwakesi explains that after he accepted Bonaya’s offer of redemption, Secluded Africa provided him with beekeeping training and 10 hives to get him started. The hard part was getting bees to move in. “We call this sungu, or bee glue,” he says, holding out an ugly, pitted, brown bulb. “It’s tree medicine that attracts bees. If you put it in the hive, hopefully they will come.”

At peak production, each hive can produce 10 liters of honey, three times a year. With 13 hives, Mwakesi can harvest 390 liters of honey annually, which he sells for 250 Kenyan shillings a liter, giving him an annual income of around KSH 100,000 (USD$658). It’s not much, but alongside his farming and some construction labor, it keeps the wolf from the door.

“When Yusuf arrested me, it felt like the end of the world. But instead, now I have a new skill and we have become friends. I was blessed that day.”

- David Mwakesi

But beekeeping has another surprising benefit: It’s saving elephants’ lives. That’s because the elephant, the largest land animal, is terrified of the humble bee, one of the smallest.

“African bees are very aggressive,” explains Corcoran. “Elephants hate them. If they sting the soft skin around their mouths or inside the trunk it’s really painful. Even the buzzing drives them crazy. So we put beehives near the fence and this deters elephants from coming onto farmland.”

The idea of using bees to scare away elephants was pioneered by Dr. Lucy King, from the nonprofit conservation group Save The Elephants. Today, they run an Elephants and Bees Research Center and honey processing room 30 miles away in Tsavo East—where their field tests using beehive fences in three rural communities have had an over 80 percent success rate at reducing elephant attacks. They’re now also testing the scheme on Asian elephants in India, Sri Lanka and Thailand.

Before he got his hives, elephants tried to raid Mwakesi’s crops as often as twice a week. “Usually, I could scare them away by shouting and clapping,” he tells me, “but once there were two that wouldn’t leave. By the time I had run to fetch help, they had destroyed everything.”

Now, however, the elephants leave him alone. “I see them pass by, but they don’t come close. I think they can smell the bees, or hear the buzzing, so they look for food somewhere else.”

David sells his honey back to Secluded Africa to be served in the lodges. “It’s a win-win-win-win,” says Corcoran. “The elephants leave the farmer alone, the bees pollinate the crops, the farmer makes some money, and we get delicious, organic, local honey to drizzle on pancakes.”

If a tiny bee can scare a powerful elephant, I probably shouldn’t get too close. But I want to see this terrifying insect for myself, so I ask Mwakesi if I can see inside one of his hives.

Carefully, he removes the wooden lid and I peer into the dark tube. It’s empty, with just a squiggly white print where honeycomb used to attach. No bees at all.

In June, after a year of drought, Tsavo’s bees all left to seek pastures new, and Mwakesi’s hard-won source of income, like the waterholes, dried up.

What will he do now? I ask. Will he go back to poaching? Mwakesi shakes his head vigorously, no. “It wasn’t worth it,” he says. “I was risking my life every time. I couldn’t even sell the meat because people knew it was illegal. When I tried, one guy took it and refused to pay me because I couldn’t complain. So now I just have to wait for the rain and pray the bees come back soon.”

Despite the challenges, he remains hopeful. “When Yusuf arrested me, it felt like the end of the world. I thought I would go to prison. But instead, now I have a new skill and we have become friends. I was blessed that day.”

The blessings seem to continue to come. In November, it started raining again, finally, in Tsavo.

**

The writer was hosted by Secluded Africa at Kipalo Hills Lodge in the Mbulia Conservancy. Transport within Kenya was arranged by Audley Travel.

***

Adventure.com strives to be a low-emissions publication, and we are working to reduce our carbon emissions where possible. Emissions generated by the movements of our staff and contributors are carbon offset through our parent company, Intrepid. You can visit our sustainability page and read our Contributor Impact Guidelines for more information. While we take our commitment to people and planet seriously, we acknowledge that we still have plenty of work to do, and we welcome all feedback and suggestions from our readers. You can contact us anytime at hello@adventure.com. Please allow up to one week for a response.

Bella Falk is a travel writer, photographer and documentary director from London. She writes the travel blog Passport & Pixels, which has won or been a finalist for more than 20 industry awards, including winning Blogger of the Year at the British Guild of Travel Writers’ Awards 2023. Her words and images have been published by National Geographic Traveller, Wanderlust, BBC Travel and Lonely Planet among others.

Related

Against all odds, one man is making honey in the desert of Qatar

The ground beneath our feet: Can regenerative farming save our food?

The Maasai school teacher using tourism to empower women

Too good to be wasted: Meet the Indian chef who’s turning food scraps into gourmet bites

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: