Satiating her taste for the esoteric, travel writer Samia Qaiyum sets out to observe the Sufi dancing ritual of dhamaal during a solo trip across Pakistan.

Satiating her taste for the esoteric, travel writer Samia Qaiyum sets out to observe the Sufi dancing ritual of dhamaal during a solo trip across Pakistan.

“It’s awfully brave of you to be here if you don’t mind me saying,” remarks a spectacled young engineer named Farhan, taken aback by my presence. We’re standing on the marble stairs at the Tomb of Shah Jamal, slowly moving away from the intoxicated crowd that’s collectively chanting among the disciples’ tombstones. There’s not another woman in the room. “Some might say there’s a fine line between bravery and stupidity,” I reply. Every so often, I feel the pull of a certain experience, and in Pakistan, that is the Sufi ritual of dhamaal.

It’s a typically smog-filled night in Lahore, a city home to several Sufi shrines and my base as I travel solo across Pakistan. He shrugs in agreement before excitedly revealing that he has shown up at this shrine—the burial place of 16th-century Sufi saint Shah Jamal—every single Thursday night for the past 14 years, come rain or shine. “I may be lonely, but I’m blessed by Shah Jamal,” he adds before offering me a joint. I politely decline, realizing this spiritual enclave has given him a sense of belonging like nothing else has. And I’m suitably intrigued.

As we make our way downstairs to the big, open courtyard for the spectacle that’s about to unfold, I reflect on the journey that led me here. My upbringing as a third-culture kid entailed exposure to only select aspects of Pakistan’s culture—the rich food, the colorful weddings, the pop-y songs of the 90s. It wasn’t until much later in life, a time when spiritual well-being was going mainstream, that Sufism piqued my curiosity.

In retrospect, it was inevitable. The 9/11 terrorist attacks happened and Islamophobia escalated, yet the narrative around this form of Islamic mysticism remained one of tolerance and moderation, which resonated with me as a young, liberal Muslim studying in the US. While wellness brands were using Sufi poet Rumi’s name to sell yoga gear and overpriced activewear, I was attending meditation sessions modeled after the whirling dervish (sema) ceremonies of Turkey.

“There are many ways to the Divine. I have chosen the ways of song, dance, and laughter,” Rumi reportedly told his followers, after which the Mevlevi Order set out to preserve his teachings over 700 years ago. Incidentally, the combination of music and movement is not uncommon in Sufism, but dhamaal—the practice of using dance to commune with God—is specific to Sufis in Pakistan.

Tonight at this smoky shrine, I know it’s now or never if I want to observe this otherworldly ritual firsthand, especially as it’s taken a few failed attempts to attend. This isn’t exactly the kind of activity one can simply look up online, nor does dhamaal take place at every Sufi shrine.

On the advice of my Airbnb host, I first made my way to the Tomb of Shah Jamal on a Tuesday afternoon, only to be asked to return on a Thursday by the friendly street vendor selling jalebi at the entrance. And when I did, he clarified that the weekly event gets going close to midnight, as the Arabic word for Friday literally translates to ‘the day of gathering.’ And gather they do. In fact, an impromptu dhamaal took place the day after a suicide bombing at the Shrine of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar back in 2017, with both men and women dancing in defiance of terrorists.

Looking upwards as they seek a higher state of consciousness, they are oblivious to their surroundings. It feels very raw. And very real.

This is no recent phenomenon, either—Sufism has been an integral part of Pakistan’s society since its inception in 1947. Further back, Islam was spread in the Indian subcontinent by 13th-century Sufi shaykhs, who preached introspection and universal love as opposed to using force.

One of the most notable aspects of the ritual of dhamaal is the dhol drums that are played during the dancing. With their distinct, sharp thuds and rhythmic beats, the drummers who play dhol drums are the nucleus of the event. And there is not a dhol drummer more famous than Pappu Sain. But I soon learn that I’m about a year late—Pappu Sain, who was globally dubbed a dhol maestro and considered it his spiritual duty towards Shah Jamal to perform here every Thursday night, passed away in November 2021.

Understandably, there’s an air of excitement as soon as his son, Qalandar Baksh, arrives. And I can’t help but stare at the scene that follows. Tall and dressed in a sparkly ensemble, he has an undeniably commanding presence, and men of all ages rush to bow and touch their foreheads to his hands as a form of reverence. Four other drummers follow and take their place alongside him on one side of the courtyard, which is accented with a heady scent—sweat mixed with rosewater and hashish.

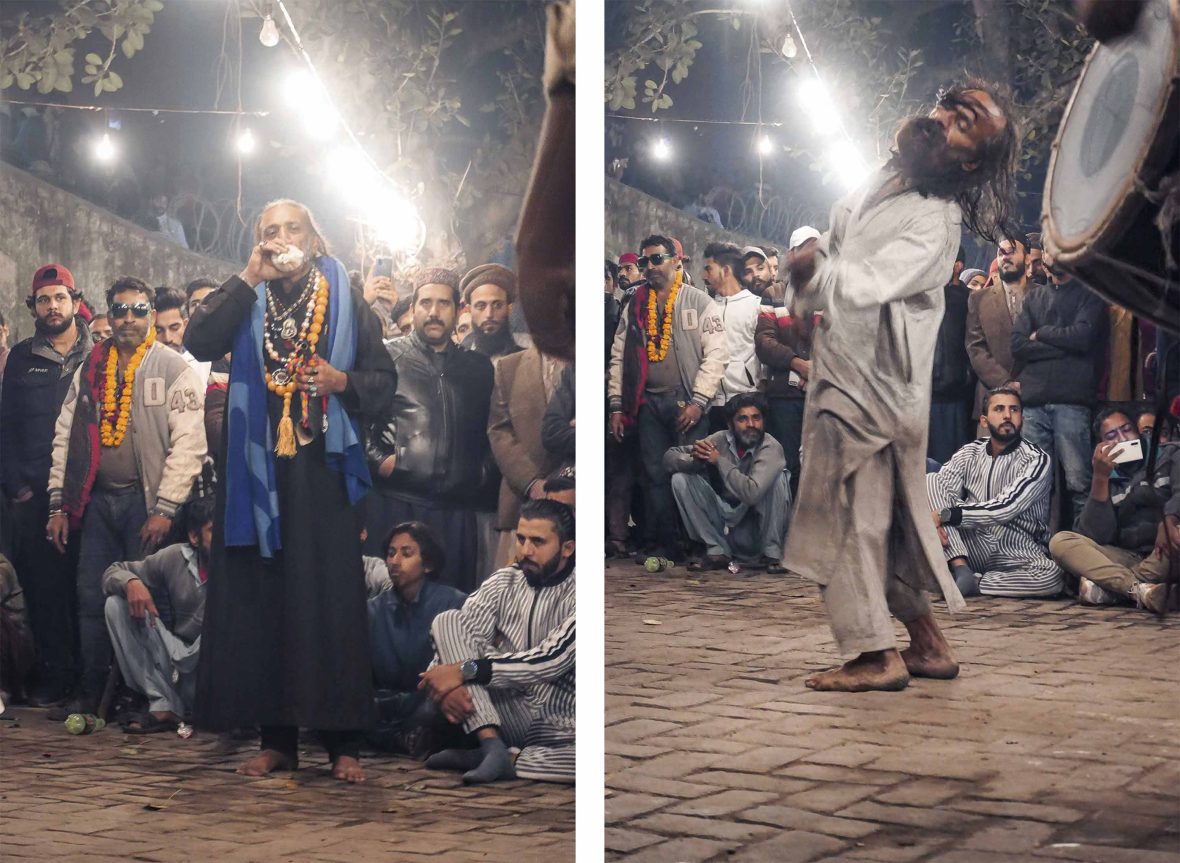

There is no time to warm up, nor is this a performance. From the moment Baksh and his peers start to beat the keg-size drums hanging around their necks with the help of leather straps, barefoot devotees flock to the courtyard’s center, dancing under the harsh lighting of naked bulbs hung on strings. They sway, they spin, they stomp their feet, they flick their wrists. Many are dressed in rags, a few wear vivid shades of red. Kufi caps, greasy long hair, waist-length dreads—anything goes. Some are visibly stoned, others are not. Looking upwards as they seek a higher state of consciousness, they are oblivious to their surroundings. It feels very raw. And very real.

Not everyone around me is lighting up, but the cloud of hashish smoke feels thicker as the audience grows, outdone only by the charged energy of the pounding drums. It’s tempting to join the spiritual mosh pit, but I contain myself, sitting cross-legged on the floor and taking it all in. With Baksh carrying on Sain’s legacy, catching this dhamaal has obviously become a social activity for some, but I’m more drawn to the drummer who’s alternating between a darbuka (Turkish drum) and the deep bass side of a dhol at a dizzying pace.

“He’s a protégé of Pappu Sain,” says Farhan, slightly slurring his words. “They spent more time together than father and son.” And it shows. There’s an intensity with which he’s playing, eyes closed, so I switch off my thoughts and close mine, too. Every preconceived notion I had about tonight is melting away as I enter a trance-like state, nodding my head to the drumbeat that is now surging through my body. It doesn’t matter that I’m stone-cold sober. It doesn’t matter that I’m a woman, an outsider, and an unexpected sight. The temporary thrill of peeking into a culture previously unknown has been replaced by the ecstasy of this sound. I get it.

Samia Qaiyum is a Dubai-based editor who specializes in travel and culture. She contributes to Elle Arabia, Vice Arabia, National Geographic Traveller, and Condé Nast Traveller. A textbook third culture kid with a perpetual thirst for adventure, she has lived in five countries and traveled to 34 others, racking up all sorts of weird and wonderful experiences along the way.

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: