Ten years of exploring and traveling around Bolivia have given author Shafik Meghji an insight into the pace and scale of the climate crisis. From feelings of despondency to moments of hope, he shares his personal journey and understanding of an ancient Amazonian culture adapting to a new world.

In 1867, so the story goes, Bolivian president Mariano Melgarejo asked the British ambassador to pay respects to his latest mistress. When the request was haughtily declined, Melgarejo took offence. The ambassador was apprehended, stripped naked, tied to an ass and paraded around La Paz’s main square, before being kicked out of the country.

When news of the incident reached Queen Victoria, she angrily ordered the Royal Navy to bombard the city. After being told La Paz was high in the Andes, 250 miles (400 kilometers) from the Pacific coast, the monarch called for a map of South America and crossed out the country’s name. Bolivia, she declared, does not exist.

I first heard this apocryphal story—the ‘black legend’—during my first visit to Bolivia in 2004. The date, protagonists and nature of the dispute change from telling to telling. But while the tale may not be true, it sometimes seems as if Bolivia really was crossed off the map.

Despite being twice the size of France, bordering Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Peru and Paraguay, and lying right in the heart of South America, Bolivia is overshadowed by its neighbors. It only makes fleeting appearances in the international media and travel writers tend to hurry through en route to somewhere else.

Yet as well as having a seismic history and some of the world’s most dramatic landscapes, Bolivia stands on the frontline of many of the touchstone issues of the 21st century: Populism, migration, the ‘war on drugs’ and—above all—the climate crisis.

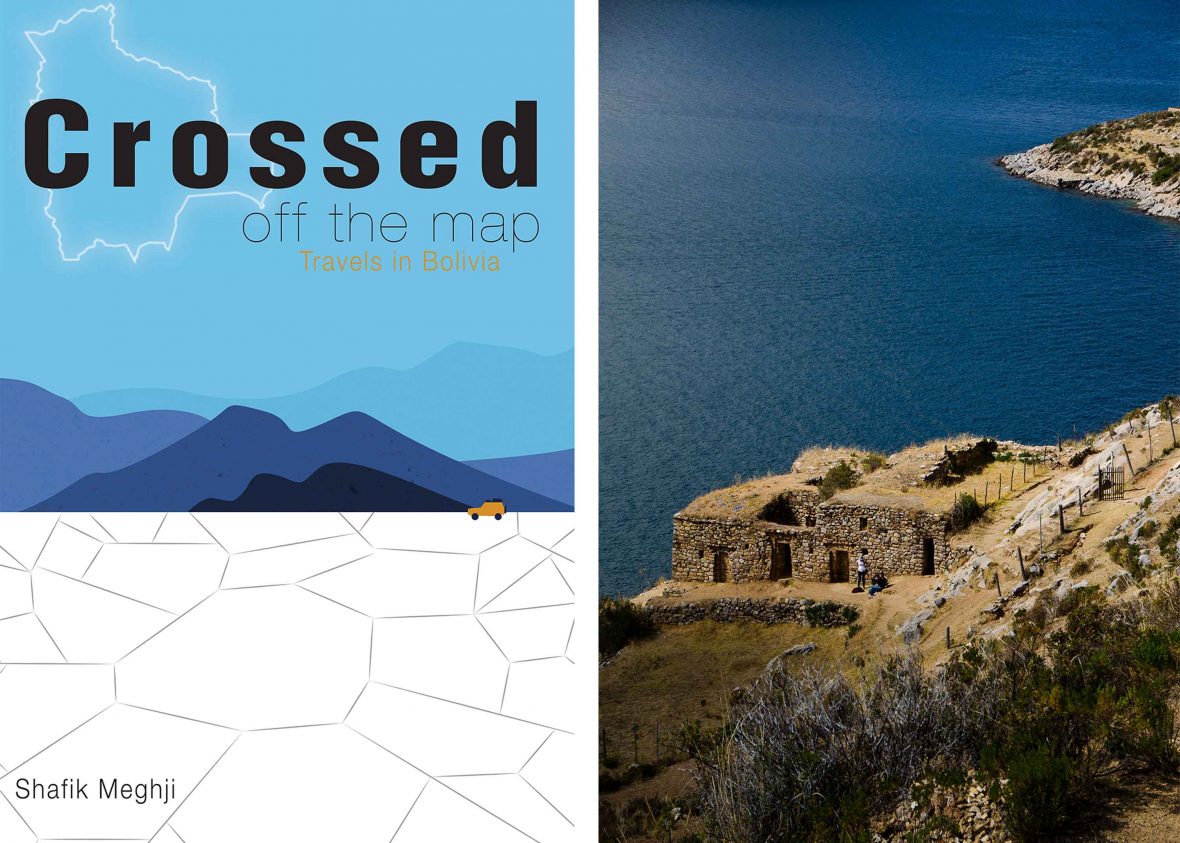

A decade’s worth of research trips for my book Crossed off the Map: Travels in Bolivia during the 2010s provided me with a striking insight into the scale, pace and impact of the crisis. In the process, an issue I’d initially planned to cover in a single chapter became a dominant theme.

One of the triggers was a 2014 train ride from the tin-mining city of Oruro across the Altiplano, a high-altitude plateau in the Andes, to the Salar de Uyuni, the world’s biggest salt flat. The Expreso del Sur railway skirted Lago Poopó, Bolivia’s second-largest lake after Titicaca and a seemingly endless expanse of greenish water. Tufts of reeds burst above the surface, fishing skiffs were visible in the distance, and hundreds of ducks and flamingos took flight as the train approached.

Poopó appeared full of life, yet the lake was already shrinking. In fact, within 18 months of my journey, it was barely two per cent of its former size. The transformation was so great I still find it hard to conceptualize—a body of water that was once the size of Luxembourg, some 1160 square miles (3,000 square kilometers), now resembles a desert.

Poopó’s evaporation was an ecological and social disaster. Tens of thousands of birds and millions of fish died, thousands of people lost their livelihoods, and shoreline settlements became ghost towns.

The causes were multifaceted: Rising temperatures, intensifying droughts, toxic waste dumped upstream, vital waterways diverted for industry and agriculture, and soil erosion, desertification and extreme sedimentation.

I found similar issues across Bolivia. In the Amazonian northwest, Parque Nacional Madidi is the planet’s most biodiverse protected area, encompassing rainforests, cloud forests, grasslands and wetlands. It is home to around 8,800 species, including at least 1,028 species of birds—roughly 10 percent of the world’s total—plus jaguars, anacondas, stingrays, spectacled bears and myriad others.

The park also faces existential threats. I encountered illegal gold miners who are poisoning the waterways with mercury and—alongside loggers and ranchers—sparking mass deforestation. Meanwhile, two proposed hydroelectric dams would flood an estimated 310 square miles (800 square kilometers) of rainforest in the region, displace thousands of people and, to quote local NGO Coordinadora Para la Defensa de la Amazonia, devastate the ‘environment, habitats, diverse ways of life’.

I later headed through the eastern lowland to Chiquitos, a realm of tropical dry forest with a scattering of 17th- and 18th-century Jesuit churches that are collectively a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This area and adjacent sections of the Amazon were subsequently consumed by wildfires. In 2019, blazes raged over more than 20,460 square miles (53,000 square kilometers), claiming the lives of at least six people and affecting thousands more. Millions of animals also perished. The fires were blamed on large-scale agribusiness-driven chaqueos—slashing and burning forest and grassland—that grew out of control. Vast swathes of Bolivia have been ravaged by wildfires in the years since.

In El Alto, the highest city on Earth, I saw how Bolivians driven from rural areas by the climate crisis and economic upheaval have created one of the most dynamic places in South America. At a breathless altitude of 4,150 meters, the fast-growing city has become a flourishing center of Indigenous Aymara culture and identity, an economic hub and the birthplace of an innovative new architectural movement, despite facing a multitude of challenges.

While I was there, my guide Jorge highlighted the Andean concept of ayni, which focuses on reciprocity, balance, solidarity and inter-connectedness. “It emphasizes the links between everyone and nature,” he said. “People should work together and make sure no-one goes without.”

In Madidi, I stayed at Chalalán, a pioneering Indigenous-owned ecolodge overlooking a caiman-filled lagoon. It was created by the Quechua-Tacana community of San José de Uchupiamonas in the mid-1990s, a response to entrenched poverty and scant government support. Chalalán has become a model for sustainable tourism and conservation, generating jobs, providing training and skills development, and funding water supplies, clinics and schools, while protecting the surrounding rainforest.

Championed by the UN, it has also inspired other Indigenous communities to set-up their own sustainable ventures, helping to create a more positive—if far from perfect—situation than in many other, more heavily touristed parts of the Amazon.

In recent years, I’ve found similar flickers of positivity across Latin America. A number of cattle ranches in Colombia’s vast Llanos Orientales—a seasonally flooded, biologically rich transition zone between the Andes and the Amazon—have created ‘natural reserves’ to protect grasslands, forests and wildlife, as well as the traditional llanero culture. In Chilean Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego, the 1,700-mile (2,736-kilometer) Route of Parks—launched in 2018 and spanning rainforests, wetlands and ice fields—combines conservation on an epic scale with responsible tourism and economic development for local communities.

Several large-scale rewilding projects are underway in Argentina, including in the Iberá wetlands in the northeast, where rare and endangered species such as jaguars and scarlet macaws are being reintroduced. And at the COP26 summit in Glasgow in November 2021, Ecuador, Colombia, Panama and Costa Rica announced plans to extend and connect their marine reserves to create a ‘safe pathway’ for wildlife stretching from the Galápagos in the south to the Cocos islands in the north.

As with their counterparts in Bolivia, these projects are open to criticism and tell only part of the story. But they show that meaningful change to protect the environment and harness the positive aspects of tourism is possible—particularly when concepts such as ayni are at the forefront.

****

Shafik Meghji is the author of Crossed off the Map: Travels in Bolivia which was published in March 2022.