While the Trump administration censors stories of slavery, displacement, and climate change, countries like Australia and Canada are finding strength—and visitors—in honesty.

While the Trump administration censors stories of slavery, displacement, and climate change, countries like Australia and Canada are finding strength—and visitors—in honesty.

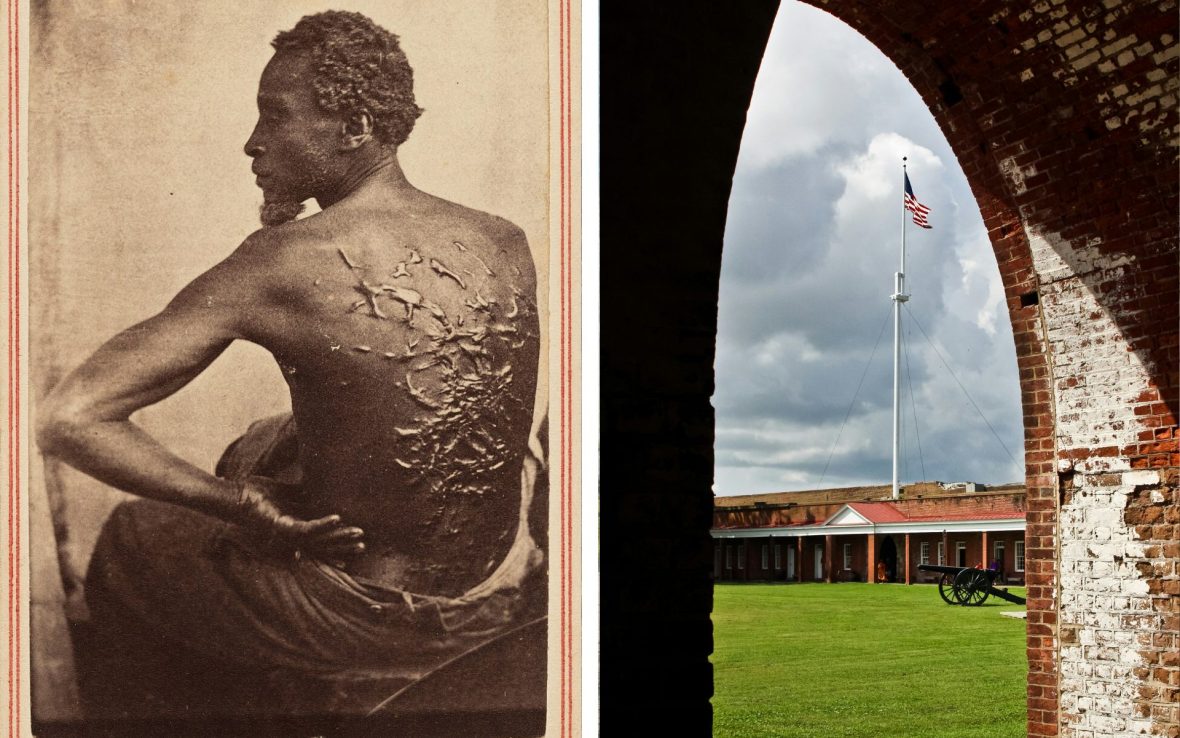

A few months ago, visitors to Fort Pulaski National Monument in Georgia noticed something missing. The famous 1863 photograph known as ‘The Scourged Back’—which shows an enslaved man’s back marked by deep scars—had quietly disappeared from its exhibit. Internal emails obtained by The New York Times and corroborating reporting by E&E News indicate staff were instructed to remove or cover the image as part of a sweeping review of “negative” content in national parks. (The Department of the Interior later denied ordering its removal, but those who were there say the photo had been taken down.)

That blank frame is part of a broader, top-down push from the Trump administration to sanitize the narratives our national parks can tell—especially about slavery, Native American dispossession, environmental degradation, and social strife. A March executive order, titled ‘Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History,’ demands that the Interior Department ensure interpretive materials do not “inappropriately disparage” Americans past or present. Under that directive, more than 400 park sites’ signs, exhibits, digital content, and gift-shop displays are under scrutiny. As Reuters reports, “all interpretive signage in national parks is under review.”

The stakes of all this are high: When we sanitize the stories our parks tell, we don’t just lose historical accuracy—we lose the chance to understand one another through the full story of this country. These lands were meant to hold truth, not whitewash it.

Beyond the Fort Pulaski photo, parks have been told to remove signage noting that lands once belonged to Indigenous nations, or to alter displays that highlight forced removals and broken treaties. At Manassas National Battlefield, signs critiquing Lost Cause mythology—a post-Civil War interpretation that romanticizes the Confederacy—and calling out slavery’s role in the war, were flagged.

At Independence National Historical Park, exhibits about George Washington’s enslaved workers were called out as “corrosive ideology,” and set for rewriting. At Arlington House, the historic mansion built by George Washington Parke Custis as a memorial to George Washington, staff were ordered to stop distributing a children’s booklet explaining how Robert E. Lee had broken his oath to the US by joining the Confederacy, according to The Washington Post.

If you strip away the painful chapters, you deny those communities a connection to public lands. Why go to a park that refuses to acknowledge your ancestors’ struggles?

This purge isn’t limited to human stories. Climate-related signage and content is also targeted. Acadia National Park, for example, had panels removed that explained how rising seas and severe storms were reshaping the coastline. Officials have flagged webpages about climate impacts in places like Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park and Lake Mead National Recreation Area for alteration or removal, according to the National Parks Conservation Association.

In some parks, employees have been asked to report “non compliant” content via a QR code—a kind of ideological self-policing that chills honest interpretation. “Pretending the bad stuff never happened is not going to make it go away,” said Alan Spears, NPCA’s senior director for cultural resources.

The Trump administration’s whitewashing of National Parks fits with a broader rollback of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) across federal programs. Under Trump’s leadership, DEI offices were dismantled, affirmative-action requirements for federal contractors were rolled back, and federal institutions—universities, museums, government agencies—were pressured to purge programs deemed too focused on race, gender, and inequality. The national park purge is an especially powerful piece of that puzzle: By defining what is allowed to be said in public spaces of memory and national identity, you shape collective memory itself.

And memory matters. The people who visit national parks already skew predominantly white—88 to 95 percent of all visitors to national forests and parks are made by white people, according to U.S. Forest Service data from 2018-2022—and communities of color have long complained they see little of their own stories or heritage in park narratives. If you strip away the painful chapters, you deny those communities a connection to public lands. Why go to a park that refuses to acknowledge your ancestors’ struggles? Over time, that exclusion erodes legitimacy and support.

At the same time, the narrow narratives left behind risk turning parks into hollow showcases—pretty but empty, lacking emotional resonance and moral challenge. Visitors may leave feeling light and untroubled, not informed or changed. That’s not what our national parks should do.

The United States is not alone in confronting how parks link to identity, power, and justice. Much of the world is moving toward more inclusive, truthful storytelling—and often reaping social, cultural, and financial dividends for it.

The lesson seems to be clear: Tourists increasingly seek authentic, meaningful connections to a place. In those contexts, truth becomes a selling point, not a liability.

Take Australia. After decades of advocacy, Fraser Island was officially renamed K’gari, restoring the Butchulla name. As Dr. Rose Barrowcliffe, a Butchulla researcher, told The Guardian: “K’gari is incredibly well known … We have a huge amount of international visitors that come to see K’gari every year.”

That change not only restores cultural dignity—it becomes a draw in its own right. Australia’s First Nations Naming Project has also renamed North Stradbroke Island to Minjerribah and Moreton Island to Gheebulum Coonungai, and reinstated dual naming at Uluru, all part of a national commitment to truth-telling.

In Canada, too, Indigenous renaming is underway. In British Columbia’s Gulf Islands National Park Reserve, a campground was renamed Smonećten, and interpretive panels now include Wsáneć stories of land use, travel, and stewardship. Rather than erase Indigenous presence, the park embraced it. Parks Canada also saw 23.7 million visits in 2023-24—a six percent increase over the prior year—as it deepened Indigenous partnerships and storytelling, according to Parks Canada’s 2024 Annual Report.

Elsewhere, New Zealand widely uses Māori names and integrates Māori cultural tours as part of visitor experiences in its protected lands. South Africa, post-apartheid, has shifted many reserves to center not just land preservation but the stories of precolonial and multiracial heritage, engaging local communities in co-interpretation. In a country where tourism underpins much of the national parks’ budgets, annual visitor numbers and revenue have risen dramatically in recent decades—suggesting that the parks’ welcoming of broader stories and community voices may also attract broader support and engagement.

The lesson seems to be clear: Tourists increasingly seek authentic, meaningful connections to a place. In those contexts, truth becomes a selling point, not a liability.

We stand at a crossroads. Do we want our national parks to become hollowed-out memory zones that affirm nationalism—or spaces where complexity is honored, multiple voices are heard, and visitors walk away with both wonder and reflection?

The blank frame at Fort Pulaski is a quiet rebellion. It signals that if we don’t act, we may lose more than a photograph. We may lose a shared capacity to reckon with our past and to build a more honest national story.

It’s time to push back: Restore the removed exhibits, rescind the directive to purge difficult truths, and insist that the National Park Service recommit to its founding mission—to tell America’s full story, without shame or censorship. These are public lands. Let’s not let them become curated propaganda.

***

Adventure.com’s reporting on US National Parks and public lands is made possible by the financial support of Intrepid Travel, as part of its United by Nature campaign. The support from Intrepid enables Adventure.com to invest in high-quality journalism and storytelling at a critical time for our wild places. Intrepid is not involved in any decisions made by Adventure.com’s editorial team. If you have leads, ideas, tips for our US National Parks and Public Lands bureau, please send a confidential email to hello@adventure.com

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: