The new home of one of Africa’s most thrilling music subcultures, the village of Rakops in Botswana has just hosted its first Vulture Thrust Metal Fest. Jamie Fullerton joins 200 Botswana metalheads and experiences it for himself.

The new home of one of Africa’s most thrilling music subcultures, the village of Rakops in Botswana has just hosted its first Vulture Thrust Metal Fest. Jamie Fullerton joins 200 Botswana metalheads and experiences it for himself.

It’s nearly sunrise, and in a dusty campsite a man named Vulture is singing—or rather gutturally roaring—a song called Genital Surgery.

Clouds of Kalahari Desert dust are kicked up by black leather boots, as around 80 metalheads flail-dance to the doomy death metal of Overthrust, Vulture’s band. Spencer Thrust, the group’s guitarist, plays his axe with his teeth. Vulture introduces a song called Kill The Bastard. A woman with red hair drops to her knees to headbang, her mane swirling to the chugga-chugga rhythm.

The diaphragm-throbbing atmosphere feels like something conjured at Download Festival or Ozzfest, but I’m on the outskirts of Rakops, a village of a few thousand people in central Botswana, that’s normally more focused on cattle farming than death metal. This weekend, though, it’s the scene of the first Vulture Thrust Metal Fest, making it the new home of one of Africa’s most thrilling music subcultures.

Botswana’s hardcore metal fans and bands have squeezed into their best leather trousers and descended on the village, following a period of COVID-19 restrictions scuppering the live shows normally galvanizing their scene. For them, the festival is a vital rekindling of music and community. For me, it’s a chance to experience an area of this famously friendly southern African country often missed by tourists.

I arrive in Rakops after a seven-hour drive north from Gaborone, Botswana’s capital. It’s a flat, sparse journey, with goats licking rainwater off the tarmac. I overtake more animals than vehicles—Botswana is around the same size as France but has a population of just 2.4 million.

I meet 37-year-old Tshomarelo ‘Vulture’ Mosaka in a mildly raucous bar, where drinkers are getting smashed on one-liter bottles of beer. A man sways to thumping dance-pop while proudly holding an enormous hunting knife. In the car park, three guys chuck a live trussed-up goat into a truck before harpooning towards the booze fridges.

With Vulture being born in Rakops and now the frontman of Overthrust, Botswana’s most prominent death metal band, the hulking musician’s leather waistcoat is constantly slapped by friendly hands in the bar.

“We’re a metal family… we love to stick together,” he says when I ask him about the Vulture Thrust Metal Fest. Having run similar festivals in the larger Botswana town Ghanzi since 2010, Vulture tried to launch this event in 2020, but it was canned due to pandemic restrictions. Two years of isolation followed as ‘Marok’—as the metal subculture is known in Botswana—couldn’t gather in numbers. When restrictions abated, Vulture says, “We felt forced to do something for them. This is the one.”

The Marok scene that Vulture inhabits is a small but passionate subculture. Overthrust formed in 2008, shortly before Vulture began organizing small festivals, crystalizing his country’s nascent metalhead community. Botswana-based classic rock band Nosey Road inspired many Botswanans to pick up guitars in the ‘90s, before Metal Orizon, a pioneering home-grown metal band, helped push the community into a heavier direction.

“When we were young in Rakops, there wasn’t much technology around,” Vulture says. “We depended on people schooled overseas bringing back music and Metal Hammer magazine.” Vulture’s uncles introduced him to Motörhead, Cannibal Corpse and Def Leppard cassettes.

“When we walk, we’re in line, to show unity and love. To show that we’re one people, like a gang. The villagers who come close to us, they then understand, and they disseminate information. They tell people: ‘We thought people who listened to rock music were bad, but these people are kind’. It’s important to do that in this village.”

- Jeremiah Ocean Ronald

Partly thanks to Vulture’s festivals, Botswana metal bands such as Wrust, Vitrified, Skinflint, Amok and Crackdust slowly grew in prominence alongside Overthrust. However, like many heavy metal communities globally, they faced prejudice from conservative naysayers. The emergence of a group of beer-swigging, black-wearing music fans must be something “anti-God,” local religious leaders said. Church groups petitioned to have metal shows canceled.

Vulture recalls meeting a government media interviewer in the band’s early days, before the death of their original drummer in 2018, whose stage name triggered the interviewer. “Our drummer said, ‘Hi, I’m Suicide Torment’,” says Vulture. “The interviewer was like: ‘I’m Christian, I can’t handle this, I’m not going to interview you’.” In 2020, Overthrust released a mini-album named after their late drummer, who died in a car accident.

Now, Vulture organizes heavy metal parades at his festivals, to counteract misconceptions of metalheads as Satanists. In Rakops, they convene at the main hospital before marching to the village center, waving to delighted villagers. Marok in Iron Maiden T-shirts, cowboy hats and glistening leather trousers strut in single file, kicking in wide, confident arches. They occasionally break rank to dance, slapping boots as they jig.

“When we walk, we’re in line, to show unity and love,” says Jeremiah Ocean Ronald, a long-time Overthrust entourage member. “To show that we’re one people, like a gang. The villagers who come close to us, they then understand, and they disseminate information. They tell people: ‘We thought people who listened to rock music were bad, but these people are kind’. It’s important to do that in this village.”

The Marok look, I’m told, is a death metal spin on Botswana’s cattle links. “We’re cowboys!” Ronald says, before I’m taken to a small cattle post on the village outskirts. “The dress code is an identity,” says Vulture. “Leather pants, jackets, cowboy boots… the influence comes from heavy metal like W.A.S.P., Mötley Crüe and Motörhead. But in Botswana, we have cattle culture. We used to design our outfits ourselves, with our own cattle’s leather.”

At the cattle post, Onneile Nkapolelang, 40, hauls up a docile brown calf from his family’s small animal collection. Most families in Rakops, he says, keep cows or goats for their own meat consumption, and sometimes to sell.

Nkapolelang points to another calf. He says it was recently stolen, but he managed to retrieve it, partly due to the tightness of Rakops’ cattle community. He’s in a WhatsApp group that pings into action if a group member’s animal goes missing. “If there’s a stray cow here at my post, I take a picture and put it in the group so we can identify it,” he says.

Cattle owners like Nkapolelang sometimes have to deal with big cats taking their stock. Rakops is 70 kilometers south of the main tourist entrance of Makgadikgadi Pans National Park, a government-owned reserve populated by lions, cheetahs, thousands of zebras, elephants, hippos, giraffe, vultures and wildebeest.

Accessed via a perilously sandy off-road drive, the park’s vast open plain is an incredible sight. Elephants jostle with zebras for prime drinking space at the river’s edge. Vultures congregate near a pachyderm graveyard. A crocodile silently glides across a lake, keeping a respectful distance from snorting hippos.

It’s a spectacular tourist trip, but the animals the government protects cause problems for many locals, says Margaret Kgomo, Makgadikgadi Pans National Park’s manager. Animal dung is mixed with chili seeds and then burned, to keep elephants away from farmland. Locals can legally kill protected predators like lions—if they do so in immediate response to an attack on them or their cattle. But Rakops residents tell me that lion-hunting groups are sometimes formed by farmers, who lie to authorities about livestock being attacked.

Perhaps there’s still work to do to convince the older generations that Marok are a force for good. But in Rakops, as the heavy metal party continues into Sunday morning, it’s clear that the Vulture Thrust Metal Fest has been a success.

The government offers compensation for animals killed by protected species, but this throws up other animal management issues. “When a male cow is killed by a lion, the compensation is too high,” says Kgomo. “It’s around 6,000 pula [$460] for a bull. So now some people tend not to take care of their livestock.”

Recently, elephants trashed the Rakops campsite where the Vulture Thrust Metal Fest takes place, but thankfully there are no such raids this weekend. The bands wait until the punishing sun sets before performing.

Scene veterans Vitrified play an intense blast of cheetah-paced death metal. Bankrupt Souls raise the bar with classy stoner rock. PMMA plays clattery fuzz-rock, while three-piece Humanitarian performs a set of tuneful metal with lyrics about human rights. Vulture’s band Overthrust struggle with tech problems—unsurprising, considering that unsecured power wires are splayed across the dusty ground—but growl through an impressive show.

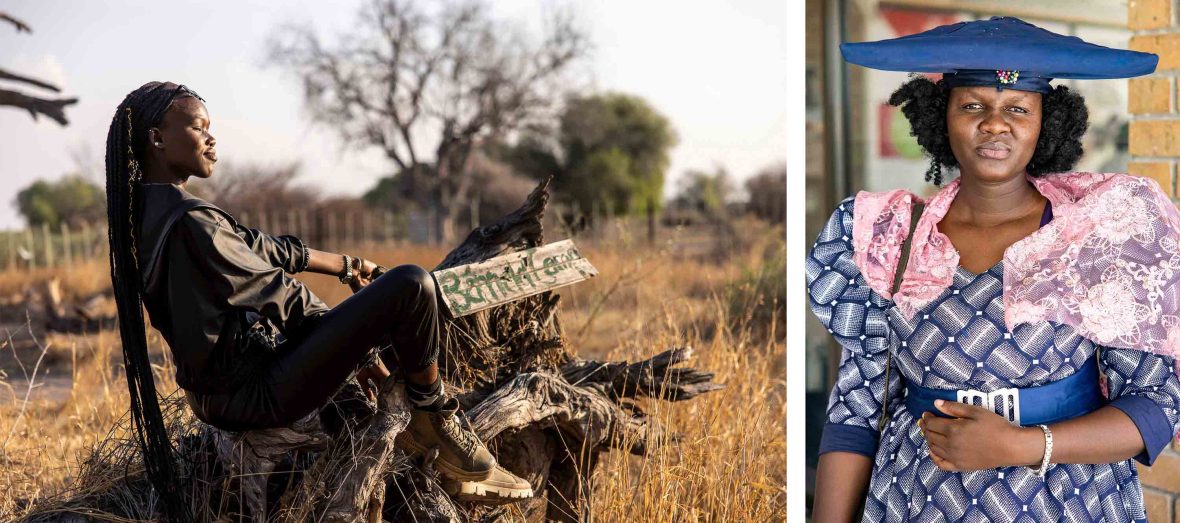

Uaendondonia Daniel, a 30-year-old teacher from Rakops, is enjoying Overthrust. Dressed in metal-compliant black, she says that her normal garb is more colorful. She’s a member of the Mbanderus ethnic group, the women of which, along with the Herero group, traditionally wear long color-blast dresses and wide hats.

“Being Mbanderus, I take pride in how we dress,” says Daniel, a former catwalk model. “We look so beautiful. I feel like it’s a reminder of who I am, and I should preserve it. When you’re wearing the dress, you have to walk in a certain way. It gives you dignity; you walk like a woman in a slow, peaceful manner.”

The older members of Daniel’s family are less approving of her festival outfit. “My grandma was like, ‘We saw people holding chains, in scary T-shirts with snakes and dragons.’ She even called my mum to tell her we were dressed like this.”

Perhaps there’s still work to do to convince the older generations that Marok are a force for good. But in Rakops, as the heavy metal party continues into Sunday morning, it’s clear that the Vulture Thrust Metal Fest has been a success.

As I leave the site, a band member shows me video footage they just took, of a large armadillo scampering outside the festival gates. It’s something else you probably wouldn’t see at Download Festival or Ozzfest, we agree, just as Die For Metal by Manowar blasts from the stage speakers behind us.

***

Adventure.com strives to be a low-emissions publication, and we are working to reduce our carbon emissions where possible. Emissions generated by the movements of our staff and contributors are carbon offset through our parent company, Intrepid. You can visit our sustainability page and read our Contributor Impact Guidelines for more information. While we take our commitment to people and planet seriously, we acknowledge that we still have plenty of work to do, and we welcome all feedback and suggestions from our readers. You can contact us anytime at hello@adventure.com. Please allow up to one week for a response.

Jamie Fullerton is a British freelance writer based on the road, most of the time. Formerly features editor of NME (when it was a magazine as well as a website), he has written for titles such as The Guardian, The Times and The Sunday Times, The Telegraph, CNN and Atlas Obscura. He once had a Top Tip published in Viz.

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: