Writer Patrice La Vigne finds that working at the iconic Iditarod race might be the hardest—albeit, most rewarding—volunteer experience she could imagine.

Writer Patrice La Vigne finds that working at the iconic Iditarod race might be the hardest—albeit, most rewarding—volunteer experience she could imagine.

It took one fateful phone call to learn that pulling all-nighters, scooping dog poop, and doing back-breaking work in notoriously awful weather is the immersive experience I didn’t know I needed.

And I vividly remember that phone call coming in about a year ago.

My husband, Justin, was talking with a fellow hiking guide, who happens to be one of the logistics coordinators for the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race. I assumed they were discussing a potential winter guiding trip for Justin to lead.

“So we’d be winter camping, right?” Justin asked tentatively. “Patrice and I don’t own an arctic oven tent or a sleeping bag that’s 40 below.” A few more “uh huh’s,” then I heard him say, “Let me talk with Patrice, but I’m 90 percent sure you can count us in.”

Record scratch. What wild-minded adventure was I being roped into?

Justin and I calculate risks differently. I like to say he’s the gas pedal, and I’m the brakes. Still, most of his unknown paths turn into unforgettable memories, and his convincing personality can sell manure to a farmer. And here we were with a new proposition: Working as trail crew volunteers for the 2022 Iditarod race.

Important side note: I might be the only Alaskan who’s not a dog person. I feel the same way about dogs that I do about pepperoni pizza; it might be popular, but it’s not my jam.

You’re operating outside your comfort zone all the time; it’s difficult to get perspective of what’s ‘normal’ in such an unforgiving environment.

- Dr. Molly Ebinger

Dog teams have always offered a means of transportation during Alaskan winters, and the Iditarod is a reconstruction of the route for dog mushers bringing medicine to native communities. The “Last Great Race,” as it’s called, began in 1973. Still, every year in March, about 50 mushers race teams of sled dogs 1,000 miles across Alaska.

It takes nearly 2,000 volunteers to put on such a massive event. While most live in Alaska, many come from the lower 48 and a few other countries. Duties include communications, logistics, shuttle drivers, trail crew, veterinarians, dog handlers, pilots, food packers, and more.

There’s no sugar-coating the volunteer experience. It’s almost a guarantee that you’ll be so sleep-deprived that your gas tank will run on adrenaline alone, and you’ll risk frostbite without the right winter gear. Not all fun is created equal, and this qualifies as type two—uncomfortable while happening, addictive in retrospect.

As brutal as it sounds, there’s a high retention rate among volunteers—even a tiny bit of competition to become one.

Jerry Trodden calls it “controlled chaos,” but hasn’t missed out in 22 years. “There’s a fair share of veterans that have volunteered for 20-plus years,” he says. “Still, a lot of people come to check a box. Lives and responsibilities change, but it’s a unique experience for those with the right attitude.”

There are 26 race checkpoints from the starting line in Wasilla to the finish line in Nome. Most are a spec of civilization on the Alaska map above the Arctic circle, accessible only by small propeller planes. Some are so remote that the plane just drops off volunteers with food and arctic tents on the barren tundra. As Jennifer Dowling, Race Comms and Trail Coordinator, promises, you’ll sleep on “some of the comfiest grounds and floors in remote and arctic locations” for free.

It’s not appealing until it is, trust me.

Justin and I were spoiled by our first volunteer digs. We were stationed at mile 545 of the race course in the native village of Galena along the Yukon River. The checkpoint was within the spacious community hall complete with flush toilets, plus sleeping quarters separated from the 24 hours of activity via a makeshift wall. When I claimed my cot, I remember the advice to always make it look occupied, just in case a stinky musher decides your sleeping bag looks like a good place to pass out. Other pro advice: Eye masks and ear plugs are a must to squeeze in naps.

Though Galena’s population is only 450 people, the village offered the warmest welcome. The Iditarod flies in a food shipment for volunteers, but bad weather delayed ours by days. We visited the unassuming corrugated metal building housing a tiny grocery store to cobble together grub for 10 people. Word got out to the community about our plight, and in a matter of hours, caribou stew, salmon fillets, and moose chili started pouring in.

Some people are incredibly envious of being able to experience the wonders of Alaska in a way that many aren’t able to. Others are pretty sure that I have some substantial issues.

- Lynne Danielson

In 2022, Dr. Molly Ebinger spent three weeks at several checkpoints—Nikolai, Unalakleet, Safety, and Nome. As a rookie veterinarian on the Iditarod trail and being from Kansas City, there were lots of firsts for her: Her first time in Alaska, her first time experiencing arctic weather, her first time on a small plane, her first time on a snow machine.

“You’re operating outside your comfort zone all the time; it’s difficult to get perspective of what’s ‘normal’ in such an unforgiving environment,” she says. “I relied on my senior lead team members, and if they weren’t worried, I wasn’t worried. This is exactly how the sled dogs operate: trusting their lead dogs and musher to push their anxieties aside and continue down the trail.” Ebinger has worked with all sorts of dogs (i.e. police and service dogs), and claims sled dogs are the most trusting of them all.

Time commitments for volunteers vary, but most people need to plan for 5-10 days, also considering travel to and from Anchorage (on your dime). Volunteers are warned to be as flexible as a rubber band—the race coordinators joke that your assignment isn’t set in stone until you deboard the plane. The logistics behind herding volunteers and supplies along the trail with weather delays boggles my mind, even after experiencing it firsthand.

Dr. Erika Friedrich has been using her vacation time from her full-time emergency veterinarian position for volunteering since 2010, flying in from Virginia. It’s her way of giving back to the veterinary field and taking an opportunity to work with amazing dogs, plus she calls the event’s camaraderie “infectious.”

“Being out in conditions to which most of us are unaccustomed forges friendships,” she emphasizes. “We all become part of a family away from home.”

During our volunteer experience, Justin and I were assigned to the four-person trail crew in Galena, meaning we focused on tasks for incoming and outgoing dog teams. When the teams left, we cleaned up dirty straw, leftover food and, of course, dog poop. Every muscle in my body was politely requesting the end of the hard labor. The grand finale for our trail crew was that all four of us came down with an unidentified stomach bug following the race. Justin and I have an outhouse at home, so returning home to have our system purge itself for five days was not the extension of type two fun I was expecting.

Lynne Danielson followed in the footsteps of her mom, Eunice Thaeller, who volunteered from 1999 until 2007. Now in her 15th year of volunteering mostly in Kaltag and Rainey Pass, Danielson calls it a “challenge not made for the faint of heart.”

“People are pretty polarized when it comes to responses to me doing this as my vacation,” Danielson adds. “Some are incredibly envious of being able to experience the wonders of Alaska in a way that many aren’t able to. Others are pretty sure that I have some substantial issues.”

Besides the fact that you are working in subzero temperatures, the winds out on the Yukon River are so squirrely they can push snow machines sideways. The gear list recommended by the committee is no joke, especially because you often don’t know which checkpoint and what conditions you’ll endure. Temperatures of -40 Fahrenheit could be a warm day.

For eight days, I alternated between freezing to the bone and breaking a sweat. Inside Galena’s community hall, I wore my wool baselayers and socks but would pull on a fleece mid-layer, another pair of socks, snow pants, a puffy parka, 2 sets of gloves, a neck gaiter, a hat, and my boots as quickly as possible when dog teams were close.

Over Trodden’s 22 years, he’s often been unprepared, and still learns something new every year about how to dress and eat. He asked me if I’ve ever seen wind socks that are hung only feet apart point towards each other (I haven’t). He said that’s when you know the conditions are really bad.

“The mushers and native villagers are people who have lived their whole lives outside in rhythm with the seasons and could never consider any other way. I learned from them to eat high-fat snacks before bed to stay warm. I’m not talking nuts, I’m talking muktuk [a traditional native delicacy of whale blubber] or spam,” Trodden says.

One caveat he passed on to me: Never pack a button-down shirt. Try buttoning buttons with gloves on at 30 below in a tent. You can’t, so getting dressed will take 30 minutes in between warming hands.

It’s impossible to encapsulate the spirit of the dogs, mushers, volunteers, and Alaska Native communities, but Justin and I are hooked on being part of the team behind the historical race and will be back to volunteer again this year and beyond. I guess that means Justin can sell dog turds to non-dog lovers, too.

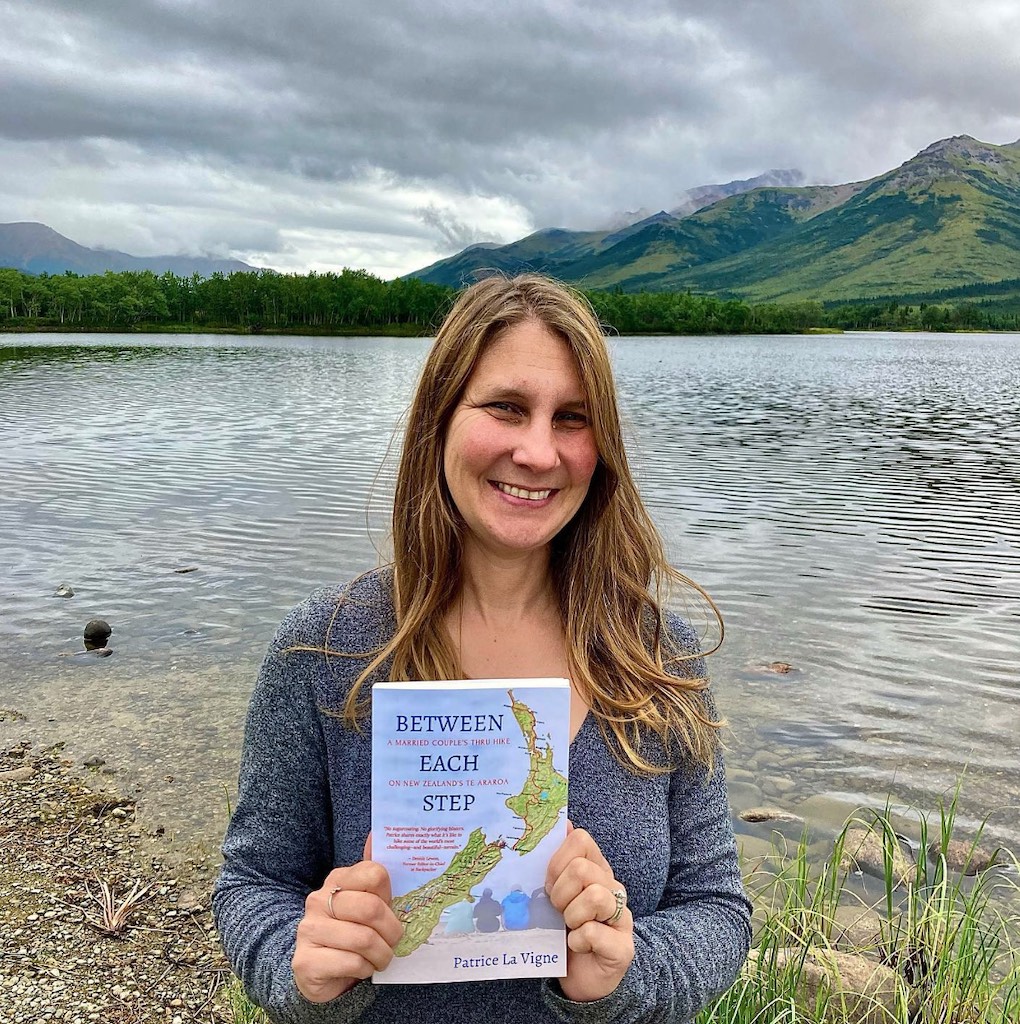

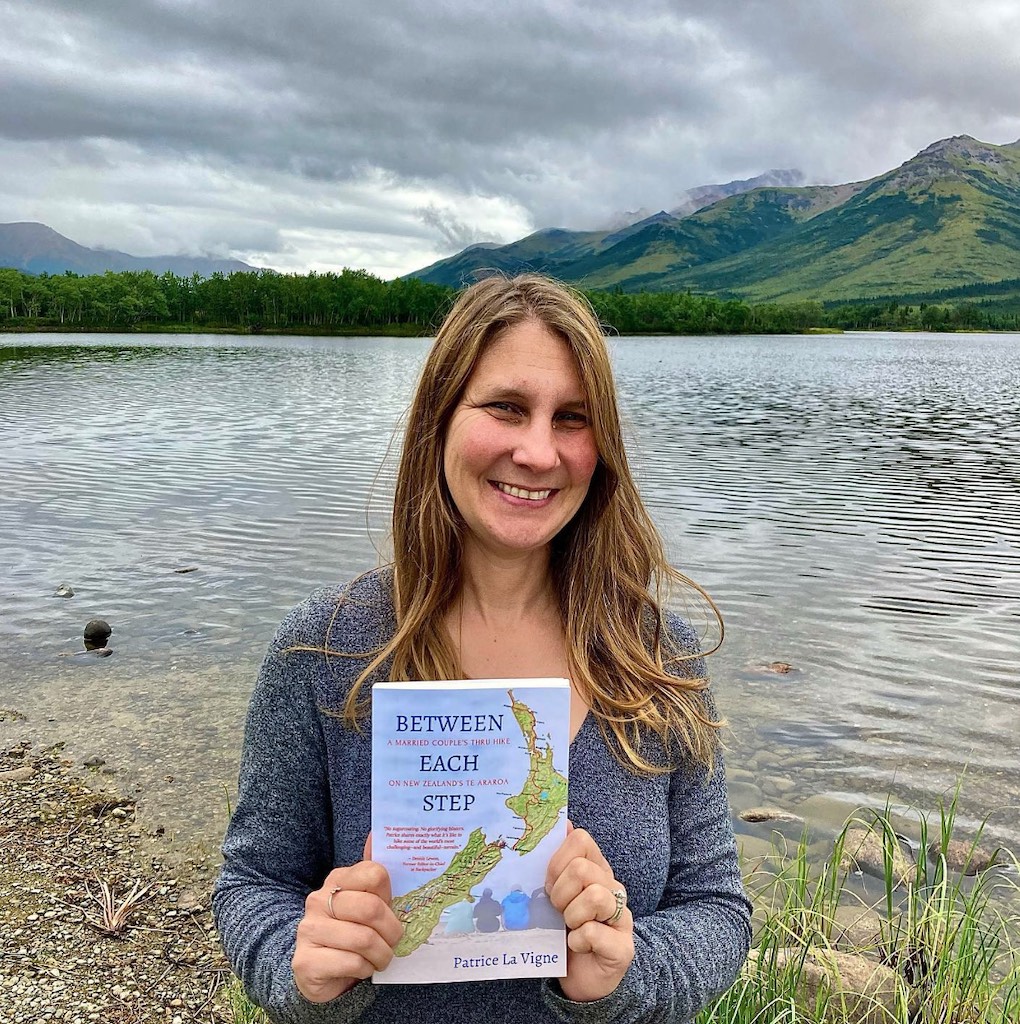

Patrice La Vigne is a freelance writer and author of 'Between Each Step'. Her bylines include Backpacker, Outside, Outdoor Business Journal, GearJunkie and Alaska Magazine. Though she lives in Alaska, she’s backpacked more than 6,000 miles on trails around the world and has road-tripped across America at least 40 times.

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: