Editor’s note: This article was published before the coronavirus pandemic, and may not reflect the current situation on the ground.

They’ve inhabited the Venezuelan Delta for centuries, but now, the encroachment of oil and mining industries means the Warao people’s way of life is under threat. Photographer Adriana Loureiro Fernández pays them a visit.

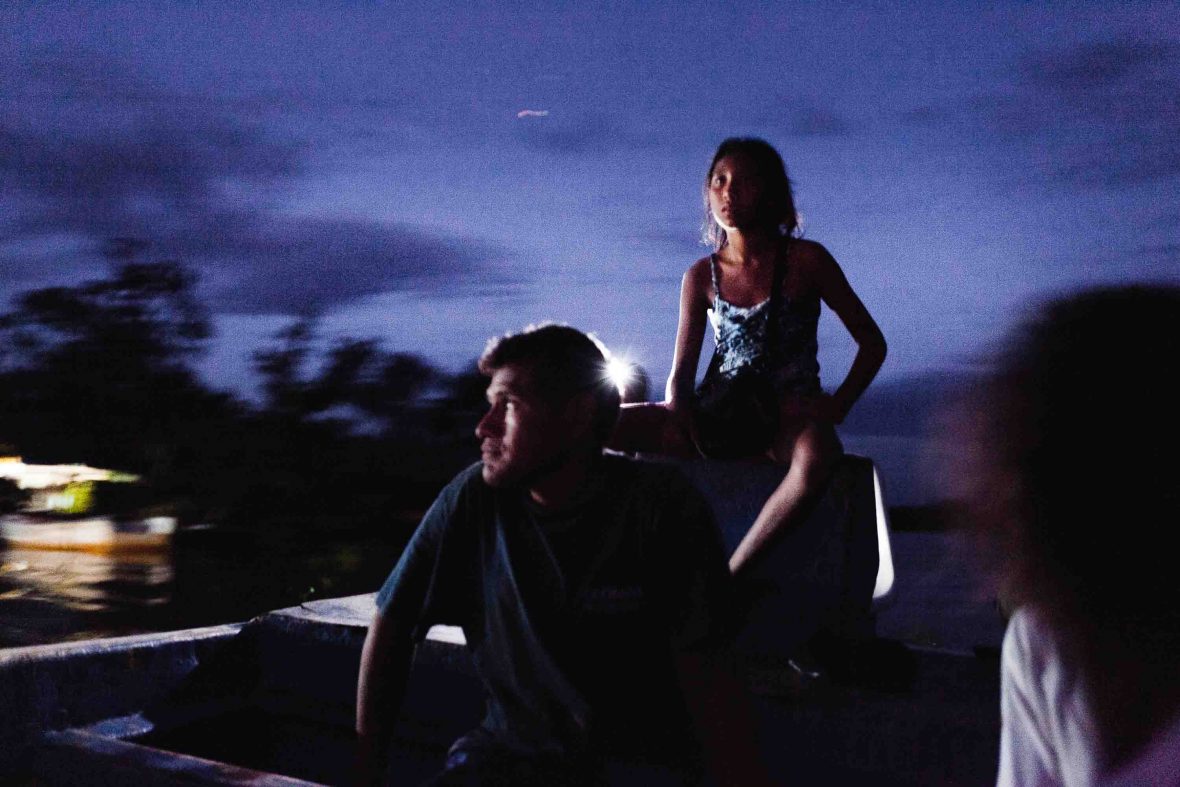

The river is barely moving, lit by

the last beams of the setting sun. People have gathered to take the last

motor-propeled boat heading north of Delta Amacuro, Venezuela’s most remote northeastern

state.

The Venezuelan Delta is the

region where our longest river, the Orinoco, merges with the Atlantic Ocean.

There’s little land there, most of it is swamped, as the river mouth penetrates

everything above and below.

It’s also the land where one of Venezuela’s indigenous tribes, the Warao, have lived for centuries and their staple architecture is known for its adaptation to the environment. The palafito is a wooden shack designed to float over the water and endure its continued corrosion; and in Venezuelan culture, the Warao, their palafitos and the surrounding waters one and the same.

Warao means ‘people of the canoes’ because, centuries ago, they built curiaras from trees to navigate the Delta. Even today, the rustic curiara is their main source of transportation and remains a central part of Latin American indigenous heritage.

RELATED: Walking with the last Wakhi shepherdesses of Pakistan

Any journey into the Venezuelan Delta begins with your feet leaving dry land—from there on out, it’s just water.

As we glide through the streams, the water mirrors the red sky. The trees, framing the width of the river, soon engulf us. Our boat passes abandoned palafitos, floating like wooden ghosts: Since 2014, this ethnic population has been migrating slowly southwards.

Oil extraction, illegal mining downriver, and the change in river flow have all increasingly contaminated the water. Now the water that surrounds them—the natural element that’s embedded in their cultural identity—is their primary cause of disease. What once gave them life now brings them death.

The ethnic group has one of the highest malnutrition rates in Venezuela, mostly because they are no longer self-sustaining. Their main food source is mono, a small but nutrient-dense fruit that they prepare as juice. They soak it overnight to loosen the flesh before separating it from the seed using a mortar and a pestle. The preparation of mono is laborious, but it’s all they can collect in large quantities.

The indigenous population is at risk of disappearing, along with its cultural heritage. The scale of the loss is only truly understood through the experience of this place and its people—the connection between both is tangible, and deeply spiritual.

According to Venezuelan authorities, over 3,000 Warao are currently living as refugees in Boa Vista (the capital of the Brazilian state of Roraima), and the numbers are only expected to increase, with no relief in sight for them. It is the first time in their history that the Warao have left the Delta.

RELATED: Inside the lives of Mongolia’s last nomads

But even in their plight, some Warao have chosen to stay. In the Yabinoko community, the Warao built a hut above waters with a water-purification system. The construction is inspired by the palafito architecture and designed for eco-tourism. There, tourists sleep in hammocks, just as the Warao do, and they experience everyday life among indigenous tribes.

After the sun sets, a bonfire illuminates the river while canoes pass up and downstream. Silence takes over and constellations start to form in the night sky. The Delta experience is like no other: Exotic, spiritual and grounding. It’s a deep connection of humanity and environment, channeled through one of the most ancient tribes in northern Latin America.