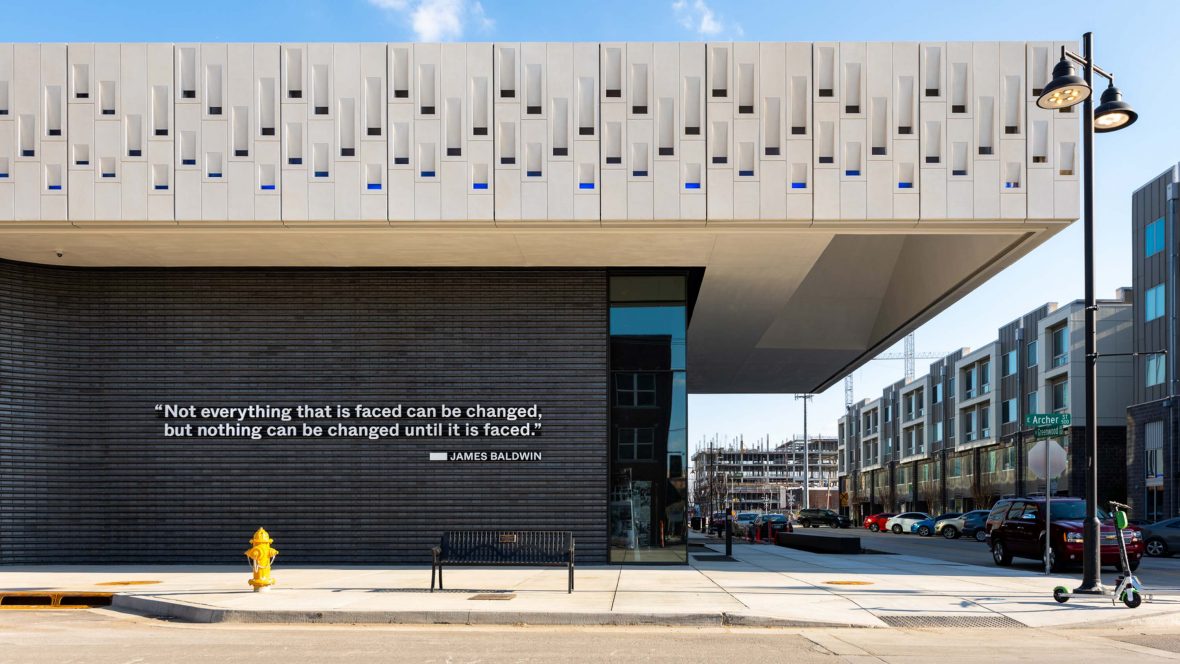

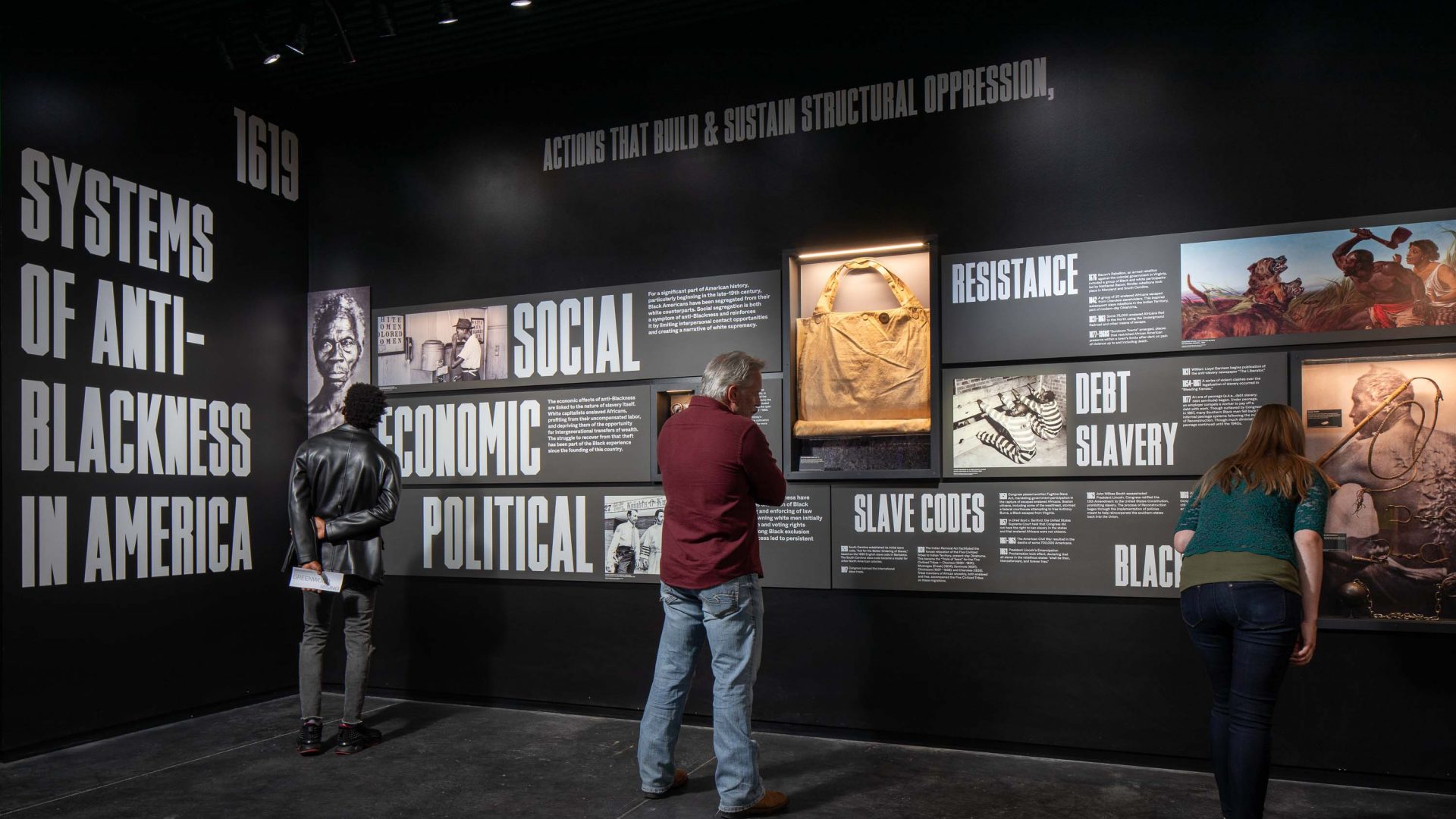

“Tulsa’s historic Greenwood District is both inspirational and aspirational,” Johnson tells me. “The historical role models who created the Greenwood District and made it into a nationally-renowned Black business and entrepreneurial hub did so against great odds, not the least of which was systemic racism in its most blatant forms.

He says the indomitable human spirit they exemplified is the stuff of inspiration. “They set the bar high for future generations,” says Johnson, “offering up something to which Black Tulsans and others could, for generations, aspire.”

RELATED: How to make friends on “America’s loneliest road

Around the corner from Greenwood Rising, I stop for a refreshing iced coffee at Black Wall Street Liquid Lounge, before browsing the graphic tees The Greenwood Gallery and colorful kicks at Silhouette Sneakers & Art next door, where owner Venita Cooper brightly welcomes every potential customer who walks through the door.

“Some of my neighbors are first-time entrepreneurs just like me,” Cooper says. “So we have definitely come together to help one another and support each other’s businesses.”