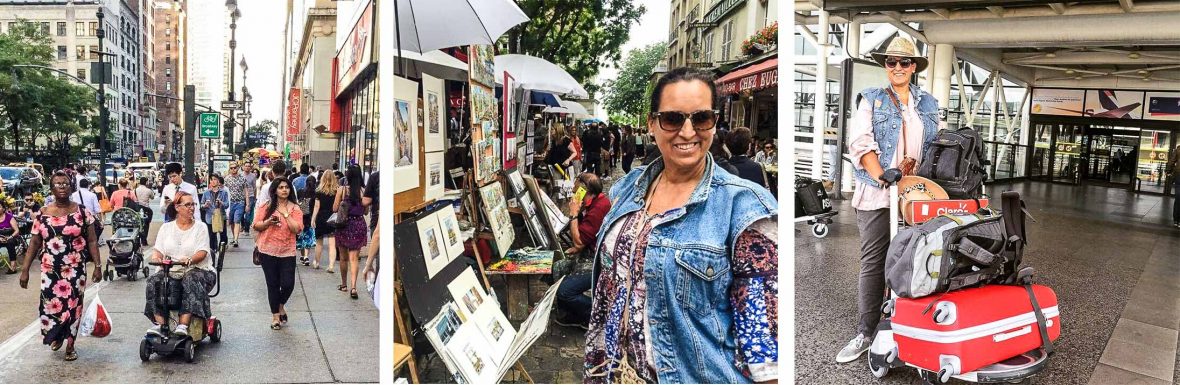

If you think traveling solo is a feat, how about traveling solo, across four continents, with a degenerative disease in your carry-on luggage? Here’s how a 53-year-old woman part-exchanged round-the-clock care for a round-the-world ticket.

If you think traveling solo is a feat, how about traveling solo, across four continents, with a degenerative disease in your carry-on luggage? Here’s how a 53-year-old woman part-exchanged round-the-clock care for a round-the-world ticket.

In northern Norway, far above the Arctic Circle, an Australian woman is holding on for dear life as she hurtles across the immaculate, ice-white landscape on the back of skidoo.

Behind her, in New South Wales, a divorce and an empty nest. Ahead, a date with the northern lights, and the promise of more adventures. She’s made it this far entirely on her own—and she’s not about to let a ‘silly little thing’ like multiple sclerosis spoil her fun now.

The back of a skidoo in northern Norway isn’t the first place you’d expect to find a woman with a degenerative disease like multiple sclerosis (MS). But then, Annie Simpson had decided to do things differently.

It was at the age of 53 that Annie’s life took a turn. Recently divorced and with her two children at university, she was living alone—it seemed her life plans, now flipped on their head, no longer made sense.

Annie had also been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis—a nerve disease that restricts her mobility—over a decade ago. She has good days and bad days, but she often struggles to stand or walk without her walking stick. On the bad days, daily tasks like getting dressed, driving and cooking can be almost impossible.

“Being married for so many years and raising a family, you lose yourself to a certain degree. But there was a point on that trip, in Mallorca, when I became reacquainted with my 20-year-old self.”

- Annie Simpson

Since her diagnosis, Annie has been conscious of the fact her life could become even more restricted as she gets older, and it’s possible she may become dependent on round-the-clock care. So, with her husband out of the picture, the kids away, and the clock ticking, she did what any sound-of-mind soul would do if they could:

She bought a round-the-world plane ticket and decided to go it alone.

It wasn’t an impulsive action; Annie arrived at her decision gradually. But as the idea of the trip—which would take her through Asia, Europe, and North and South America—percolated, she eventually decided she had nothing to lose. “I don’t think the world is as daunting as we perceive it to be from the comfort of our own homes,” Annie explains. “After all the years of being almost too scared to consider it, I had no anxiety whatsoever by the time I left Sydney.”

RELATED: Why most of my favorite explorers are women

She had traveled in her 20s, before the diagnosis, but hadn’t seriously considered a trip of similar scale since. She sought solace in the fact that she could change her ticket at any time if she needed to come home. And rather than obsessively researching the facilities on offer at her destinations, Annie decided—as she puts it—to simply live in the moment.

As she retraces the realities of traveling with MS, her no-fuss approach to the logistics of the undertaking is striking. Before booking a hotel, she would confirm it had walk-in showers and ground-floor access, but otherwise she simply asked for help to get around when she needed it. “People would just see me coming and jump ahead to open doors for me,” she recalls. “It was absolutely incredible.”

Since the central nervous system is affected in different ways and to varying degrees in people diagnosed with MS, no two cases are the same. For one person, it could mean poor coordination, trouble balancing, or difficulty using their arms and legs; for another, the disease could mean chronic fatigue, vertigo, or memory loss. And for someone else, it could result in visual disturbances, incontinence, and depression. Or it could be any combination of those symptoms—and more besides.

Not to be deterred by ‘what ifs’, Annie made a point of simply enjoying new environments, rather than ticking tourist attractions off her list. “I lost count of the number of restaurants I sat in on my own, just watching people, observing life, in all these different places,” she recalls. “I wasn’t asking ‘How am I going to manage the Vatican, what facilities does it have?’ I was in Rome for five days and I didn’t even go to the Vatican.”

Her most memorable experiences almost always came to fruition through a combination of good luck and low expectations. She rode that skidoo in Norway and made it to the northern lights, in what turned out to be a very convenient form of transportation for someone with restricted mobility. She traveled by boat up the Mekong River and stopped at villages along the way to explore them further, with the help of a tuk-tuk driver.

“My biggest challenge, and one I never imagined I would have to overcome, was hiring a car and driving on my own,” says Annie. “I had no idea how it was going to play out so my thought was: ‘Let’s just see if we can get the car out of the car park!’”

“Now, I feel that if I never traveled another day in my life, I would have seen everything that I wanted to see.”

- Annie Simpson

Annie drove over 1,500 kilometers (932 miles) through Scotland and Wales, by herself, all the while reveling in the absence of a backseat driver—and blissfully unaware of the speed limit.

“I think I learned a lot about fear,” she says, looking back on her trip. “Often, the things we fear are way off into the future; they’re not actually what’s happening right here and now. When I was traveling, I needed all of my mental and physical energy for every moment, and I learned very quickly not to waste it on worrying about what was going to happen tomorrow.”

The solo aspect of Annie’s journey was equally significant, and she says traveling in her 50s was a completely different experience to previous trips. “Being married for so many years and raising a family, you lose yourself to a certain degree,” she says. “But there was a point on that trip—I remember the day distinctly—when I was in Mallorca and I became reacquainted with my 20-year-old self.” Annie hints that a mysterious Spaniard may have been involved in this encounter, but declines to elaborate.

RELATED: The defiant Iranians hitchhiking their way to freedom

Nine months in, after achieving so much more than she ever thought she could, Annie had one more destination she just couldn’t get out of her head: Antarctica.

She’d already sailed, driven and flown independently through more countries than she even dreamed of, but on arrival in Santiago, Chile, she still felt the pull of the Antarctic. “It just dawned on me that I’d gone round the world,” she says. “I’d been to the top of the world, and to complete the trip, I needed to get to the bottom of the world. I had this strong desire to complete the whole thing.”

But her body had other plans. Acute fatigue, primarily. One of the symptoms of Annie’s MS is when the fatigue set in, it left her physically unable to keep walking—and even standing—to the extent she had been to date. “I realized that I was exhausted and I couldn’t do it, and I really was devastated,” she says. “I just never thought anything would mean so much to me.”

Earlier in Annie’s trip, when she was in Germany—long before her yearning for Antarctica—she met a woman who lived alone in a one-bedroom apartment. Her home was filled with photos of the places she had visited throughout her life. “This elderly lady told me that she often still takes trips around the world—through her photos,” explains Annie. “I really hung onto that.

“When I left Australia, I told myself that I just wanted to have memories to reflect on, as I imagined myself potentially more disabled and because I never know when it will happen. Now, I feel that if I never traveled another day in my life, I would have seen everything that I wanted to see.”

“Except for Antarctica,” she adds. “It’s the one place I still feel a really deep curiosity about.”

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: