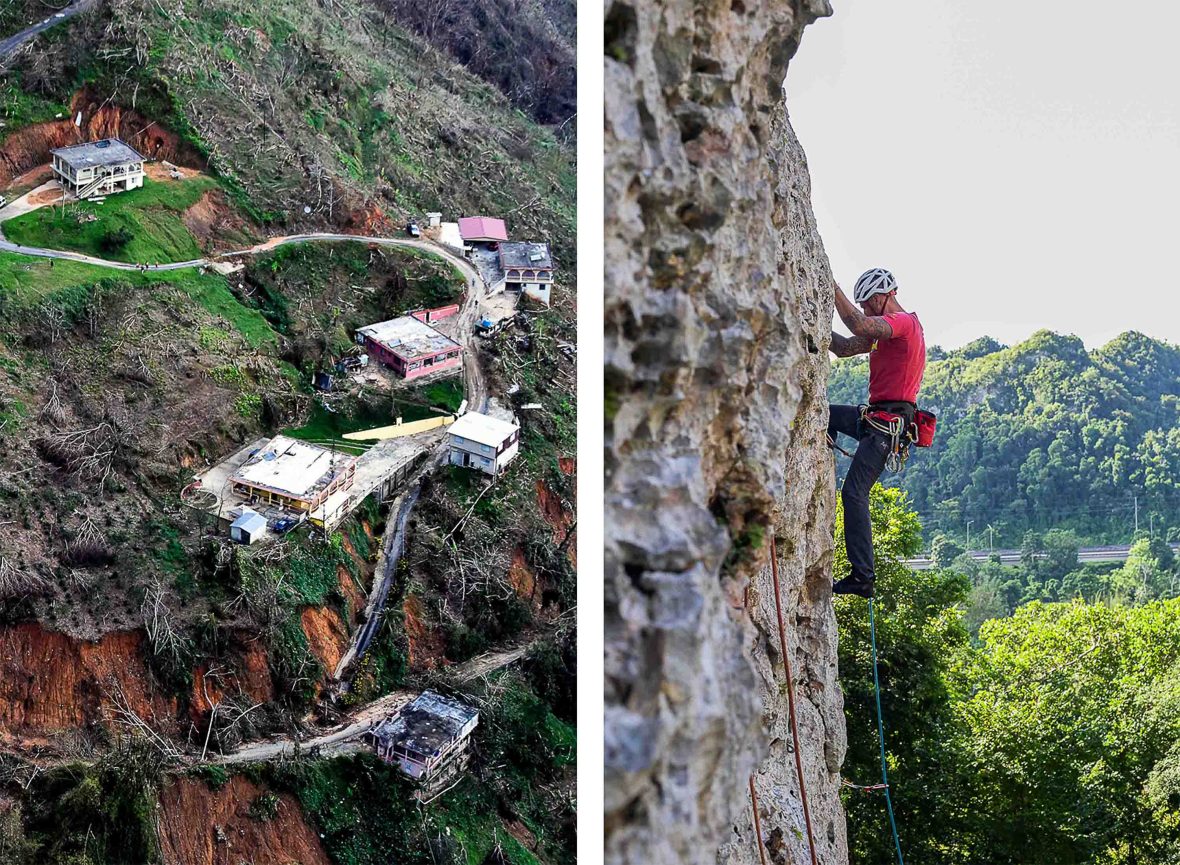

Category 5 Hurricane Maria was devastating for the islands of Puerto Rico, but seven years on, people have come together to create new eco-lodges, farm-to-table dining and ecotourism tours in a remarkable tale of recovery and rebirth.

Category 5 Hurricane Maria was devastating for the islands of Puerto Rico, but seven years on, people have come together to create new eco-lodges, farm-to-table dining and ecotourism tours in a remarkable tale of recovery and rebirth.

Sanctuary for Marianela Mercado meant her backyard; a small clearing in the Puerto Rican rainforest hidden from view by dense jungle and tall palms.

Born and raised in the center of the mainland, she and her husband Kenneth had moved to the northern coastline to settle in a region called Vega Baja, famous for its beautiful beaches and rich, fertile plains. In this secluded spot, they would spend time relaxing, lounging in a hammock they’d strung between a couple of trees, or chatting at a small table and chairs covered by shade.

“It was this magical place, you know,” Marianela recalls. “That special corner to drink coffee or some wine when you want to relax. That’s what it was for us. It just had this unique vibe of being in the jungle, but at the same time you were home. It was our happy place.”

But in September 2017, that all changed. News was coming in that a Category 5 hurricane was about to hit the Caribbean. Known today as Hurricane Maria, what followed was one of the deadliest storms the region had ever seen, with Puerto Rico hit the hardest, accounting for 2,975 of the 3,095 recorded deaths.

Marianela and Kenneth quickly fled to the central Puerto Rico mountains to ride out the storm at her parents’ house, donating their own home as a shelter for people who had nowhere safe to stay.

When they eventually returned two months later, they found the storm had ripped through their neighborhood, rendering their backyard unrecognizable. “Our happy place had been destroyed entirely,” Marianela tells me. “It wasn’t even a piece of what it was.” The trees were gone, the dense jungle flattened, and everything they had built was torn to pieces.

“A lot of people [at the time] saw the importance of going back to our roots, planting our own ingredients, improving and integrating the farm-to-table movement. We realized how it important it was for us to be self-reliant.”

- Puerto Rican local

And yet, the hurricane had also exposed a large rock face previously hidden by the forest—and with this discovery, there was a grain of hope. Both keen rock climbers, Marianela and Kenneth saw the opportunity for a new business venture right on their doorstep. Soon, from the ruins of their previous sanctuary, Roca Norte, an outdoor climbing gym, was born.

Over the course of several months, they got to work on clearing the surrounding area and making it safe to climb, allowing their newfound venture to distract from the awful destruction around them, focusing instead on hope and opportunity. “We just took it step by step, not thinking too far into the future, preparing the rocks,” says Marianela. “Being in front of those rocks for many hours was our escape.”

This is one of many inspirational stories showing how Puerto Ricans transformed the disaster of 2017 into a story of rebirth and regeneration—from the practical ways in which they now prepare for an incoming storm to the determined reconstruction of their communities. More than this, it speaks to a unique attitude and way of life that runs through the veins of every local you meet here, as I’d find out.

In the center of the mainland, about a one-hour drive from Roca Norte, sits El Pretexto, a farm-to-table culinary lodge tucked away in the mountainous region of Cayey. A trip here takes you through lush green landscapes and within close proximity to the famous Ruta del Lechón, or ‘the pork highway’, a winding route of cafeteria-style restaurants serving up whole spit-roast pig to a backdrop of live music.

Like so many other local businesses across the island, El Pretexto’s birth and growth is closely intertwined with Hurricane Maria, with the restaurant a part of a sustainable farm-to-table culinary movement. While farm-to-table is nothing new, here it’s thriving for different reasons, with the movement looking to reduce the island’s reliance on food imports.

More than 80 percent of the island’s food comes from abroad, a large chunk of which is from America (due in part to Puerto Rico’s complex relationship with the USA being an unincorporated territory of the country). When Hurricane Maria wreaked havoc on Puerto Rico’s ports, it cut off external supply chains to the island, underlying the need for a more reliable home-grown food network.

As one local, who asked not to be named, explains, “A lot of people [at the time] saw the importance of going back to our roots, planting our own ingredients, improving and integrating the farm-to-table movement. We realized how important it was for us to be self-reliant.”

Chefs like El Pretexto’s owner and founder, Crystal Díaz, addressed these challenges by not only growing their own food, but forming ties with a network of local producers to ensure businesses can keep going during the difficult months following a bad storm—while also playing a critical role in delivering fresh food to communities.

“It’s important to have these connected systems to protect the farm-to-table movement,” says Crystal. “Because of these produce systems, we’re able to call chefs and say ‘hey, we have a lot of farmers with avocados on the floor, let’s all come up with avocado recipes or things with plantains’ so we can buy a lot more and help the farmers.”

“You know, it was hard to wake up the next day and open the window, everything was destroyed. “But you need make it [life] happen again, you need to move on—it’s the only way because when you live in an island in the Caribbean, you’re used to it. You need to be ready.”

- Luz Yanira, owner, Rising Roost café

These community values and sustainable processes are knitted into El Pretexto. The 3.5-acre farm prides itself on hiring local and having an alternative concept: “We are not a restaurant.” Instead, it hosts overnight stays, pop-up dinners and farm-to table experiences, which aim to give guests a deeper understanding of Puerto Rico—and Puerto Ricans —through the food it grows, buys and cooks.

“You will get to know other types of dishes that aren’t the touristic ones. The kind of food that we eat at home,” says Crystal. “Or how we use the BBQ because the original barbacoa was born in the Caribbean through our native people, so they’ll learn about the history of cooking with this technique on the island.”

Venture east off the mainland to Puerto Rico’s small island of Vieques and it’s obvious this attitude is not just on the mainland. Minutes after arriving on a hot and sticky May morning, I get locked into a fascinating conversation with Luz Yanira, owner of Rising Roost café, over a cup of coffee. She talks about the mindset of living in a place subject to severe weather and the community ties that have formed as a result, while of course acknowledging the challenges along the way.

“A lot of us were volunteering [during Hurricane Maria]. At one time, we were volunteering for the coast guard,” she tells me. “They were exhausting days of 18-20 hours, but at the end, you just feel grateful for everything that you’re able to help with. We met so many people on this island who we would’ve never known existed.”

“You know, it was hard to wake up the next day and open the window; everything was destroyed,” she says. “But you need to make [life] happen again, you need to move on—it’s the only way because when you live in an island in the Caribbean, you’re used to it. You need to be ready.”

This mental stamina is particularly crucial for those working in the agricultural space, with their businesses heavily exposed to effects of the storm. Coffee farmers, 787 Coffee, for example, lost 90 percent of their harvest in 2017, says Christian Pagan who works at the farm located to the west of the mainland in the winding hills of Maricao.

“It basically wiped out the whole farm, it changed the environment completely,” he tells me, “but we were fortunate that people helped to clean the roads and check the condition of the trees. We just needed to start over again.”

After losing 25 coffee trees during Maria, Crystal Díaz explains how she protected future harvests as well as vulnerable fruit trees by planting them next to large, sturdier oaks for shelter. “We also have a rain-capturing system to irrigate the crops and solar power for our homes too, so we can be as ready as possible and protect our crops and our living.”

It’s clear this physical preparation is part of everyday life here, from the gasoline that Crystal makes sure she has topped up for her chainsaw—critical for clearing away debris in the farm following a storm—to the playing cards and battery-powered radio always at hand in Luz Yanira’s house. Stocking up with the local moonshine Pitorro was also on the list for one local I spoke to—but given it’s illegal to drink the potent brew outside of Christmas, they were keen to keep their identity a secret.

For others, like Sarah Elise who founded ecotourism company Crystal Clear in Vieques, living with hurricanes has almost formed into a symbiotic relationship. Sarah is an expert in coral reef and marine protection and weaves this knowledge through her snorkeling tours, where tourists can catch a glimpse of the island’s large leatherback turtle population grazing on the seafloor.

Visiting Puerto Rico today, it’s clear it’s taken time for these communities to rebuild. But seven years after the hurricane, there’s an evident buzz and swell of activity across islands like Vieques, which is seeing new critical development pop up.

She explains that in 2017, Puerto Rico was on track to experience a major coral bleaching event, but Hurricane Maria changed all that. “The interesting thing about the hurricanes coming is that we need them because they leave colder water behind. As the sea temperatures rise, that fuels the hurricanes, but then they pass and we have colder water, which gives the corals a break.

“So, I’m mentally prepared for the fact that if we get destroyed by another hurricane, we will be without power for months because I have done it before and I will do it again. Just like then, I’m not going to let go. This is my home. But I hope [if we do have another] that obviously it’s not a Category 4 or 5 and that there’s a compromise,” she says, referencing the drop in sea temperatures.

This symbiosis spreads outside the marine world too, she says, telling the story of how so many of Vieques’ famous wild horses that freely roam around the island survived the storm: “Supposedly, they just laid down”. Walk around and it won’t be long before you pass one on the side of the road. They may even come over to say hello.

Visiting Puerto Rico today, it’s clear it has taken time for these communities to rebuild. But seven years after the hurricane, there’s an evident buzz and swell of activity across islands like Vieques, which is seeing new critical development pop up.

This includes the building of its first hospital, which had previously stalled during construction, as well as the launch of new eco lodge, Lejos Eco Retreat, which offers guests an ‘unplugged’ chance to experience Puerto Rico without the distractions of wi-fi. Or the four-man team over at Crab Island Rum distillery, which has been slowly building its production of artisan rum after opening during the challenging aftermath of Maria.

All have this thread of unity in common, but more than this, a desire to not be victims of nature’s destruction. As Crystal sums up, “There’s no perfect paradise anywhere in the world. It’s how you prepare to survive during the things that happen in your little paradise.”

****

Adventure.com strives to be a low-emissions travel publication. We are powered by, but editorially independent of, Intrepid Travel, the world’s largest travel B Corp, who help ensure Adventure.com maintains high standards of sustainability in our work and activities. You can visit our sustainability page or read our Contributor Impact Guidelines for more information.

Robyn Wilson is an award-winning freelance travel journalist based in London, who regularly writes about food, music and adventure-based travel. She loves to focus on local characters and history to understand the places she visits and has been published in major outlets including The Times, The Telegraph, The Guardian, Independent, BBC Travel, Lonely Planet, Wanderlust and more.

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: