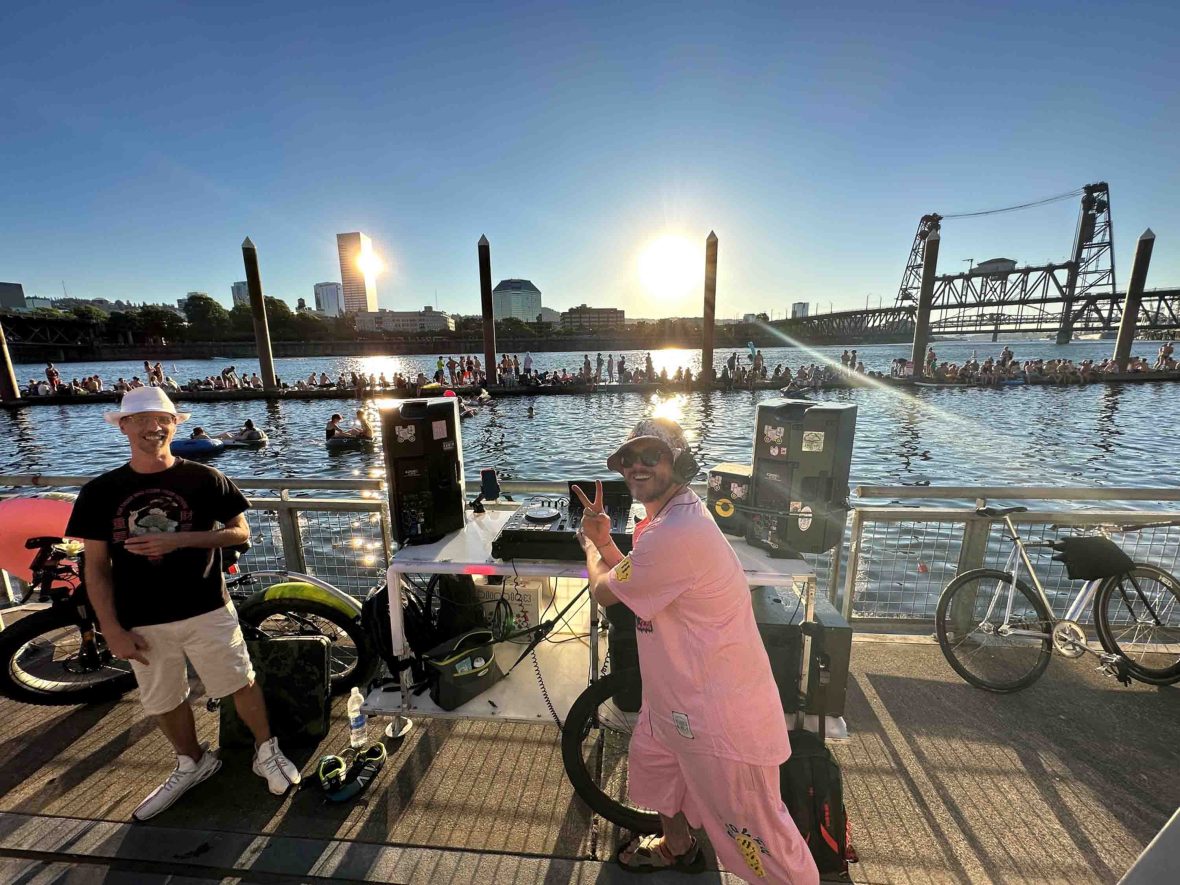

It’s the same feeling I have in Copenhagen where, toweling off after my icy plummet, I watch with both an inspired and envious heart, as locals arrive in waves to enjoy bathing in the center of their city—not thinking for even a moment that it could be some other way, that this water that laps about their famous harbor should exist exclusively for marine traffic and wastewater. It’s clear that the river is an extension of the people that live here. An extraordinary cyclical force teeming with life of all kinds.

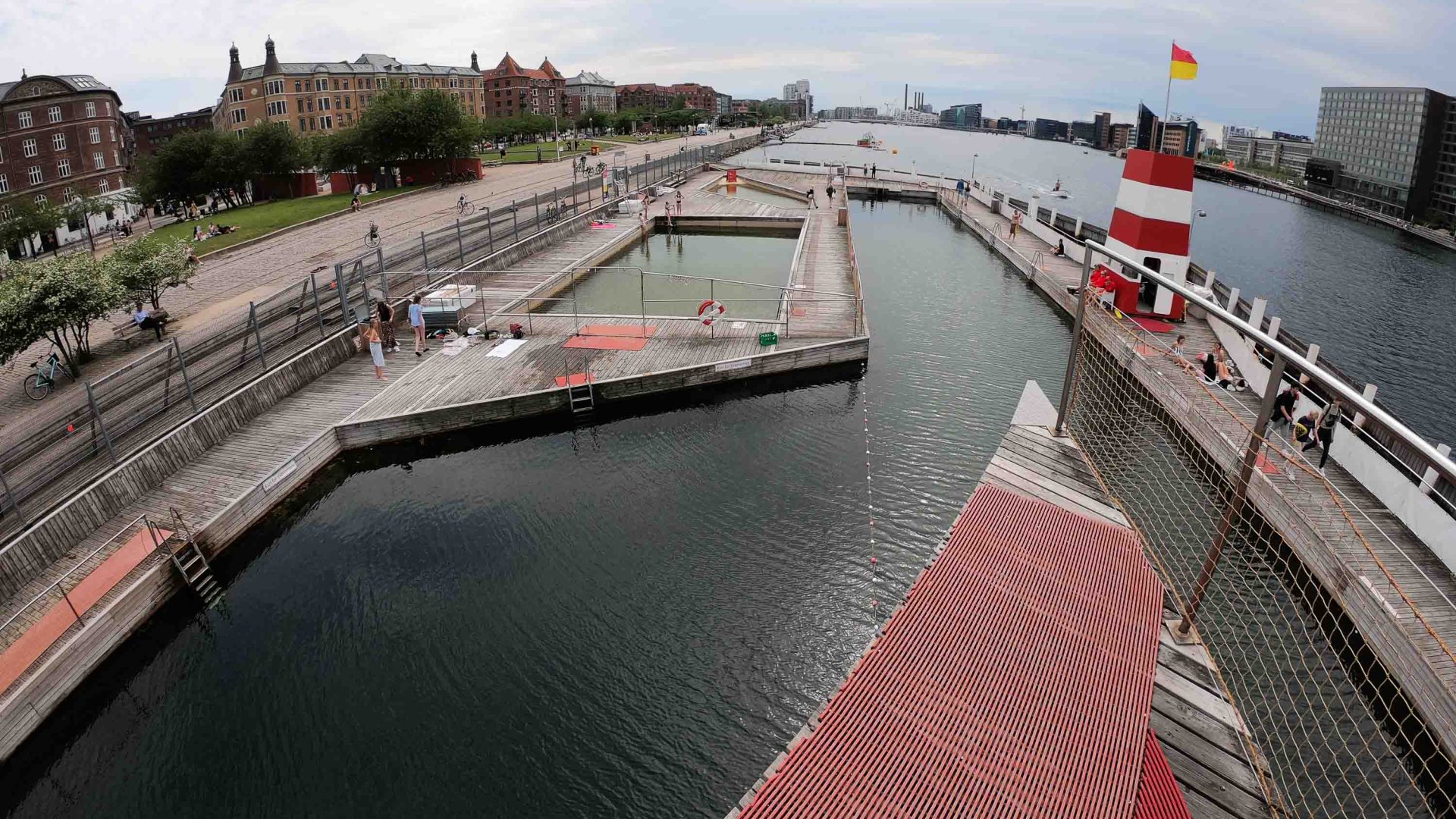

Copenhagen’s harbor—twice the size of New York’s Central Park—has been clean enough to swim in for about 25 years. As such, the three main harbor baths, which are strictly delineated to allow the space to be shared with boats, electric public harbor ‘buses’, kayakers and stand-up paddleboarders, are teeming with activity. There are biohuts (artificial fish nurseries) to help protect young fish that co-exist alongside urban farming and fisheries, six separate stone reefs, a salt-water-powered floating jacuzzi (of course!) and even compact floating apartments built to accommodate students. It really is a full vision of a swimmable city.

In one generation, Paris, Copenhagen, Basel and Rotterdam have transformed the culture and identity of their cities, reconfiguring people’s relationships with the natural world. I know that the same thing is possible for Melbourne, and so many other urban centers around the world, because it’s happened in my lifetime.

Though regenerating one river might seem like a drop in the ocean when compared to the magnitude of the climate crisis, it allows us to move beyond the existential dread, reconnect with nature, joy and each other. Change comes fast when it’s needed. And returning our rivers to their swimmable origins has the potential to help solve the greatest challenge of our time.