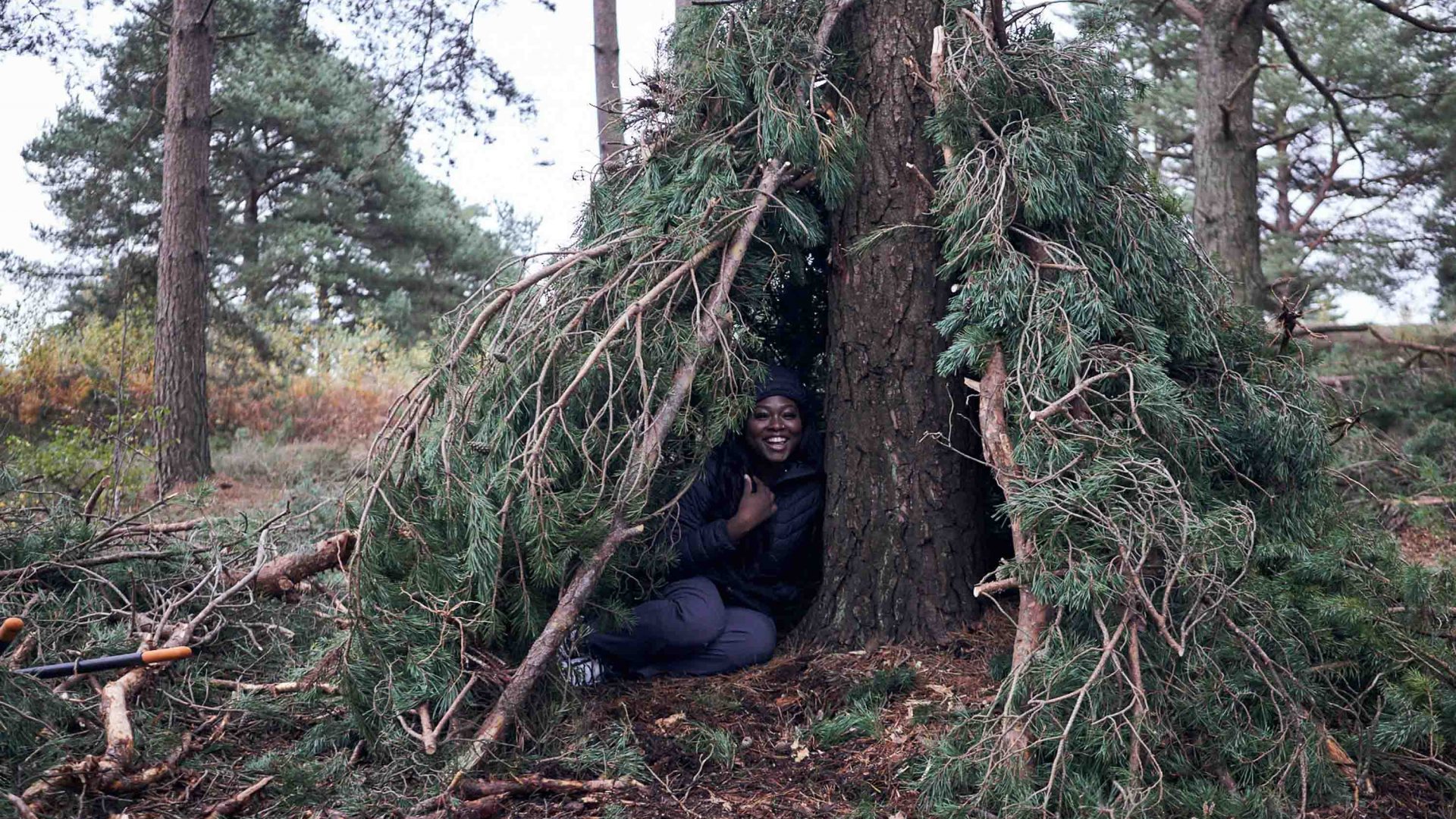

Inner-city London isn’t always easy for some of the capital’s youth, but Street Elite, an award-winning charitable programme that works to reverse the fortunes of young people on the edges of gangs and crime, is changing lives through sport and nature.

“Looking at nature is bewildering. It’s so different to London, surrounded by noise.” Ismail Mohammed is at the South Downs National Park, England’s newest national park, 85 kilometers southwest of the capital. It’s his first time in a National Park.

He’s one of several participants of Street Elite, an award-winning charitable programme devised by youth charity The Change Foundation that aims to help young people on the margins of crime and gang violence through a tried-and-tested method of sport and mentoring first, leading eventually to work, training or education.

With a growing divide between rich and poor, a lack of opportunity and direction can lead to a life of crime, where other opportunities seem out of reach. That’s why The Change Foundation created the Street Elite prevention academies, which provide young people with the skills and confidence to help them get work, apprenticeships, training or education opportunities.