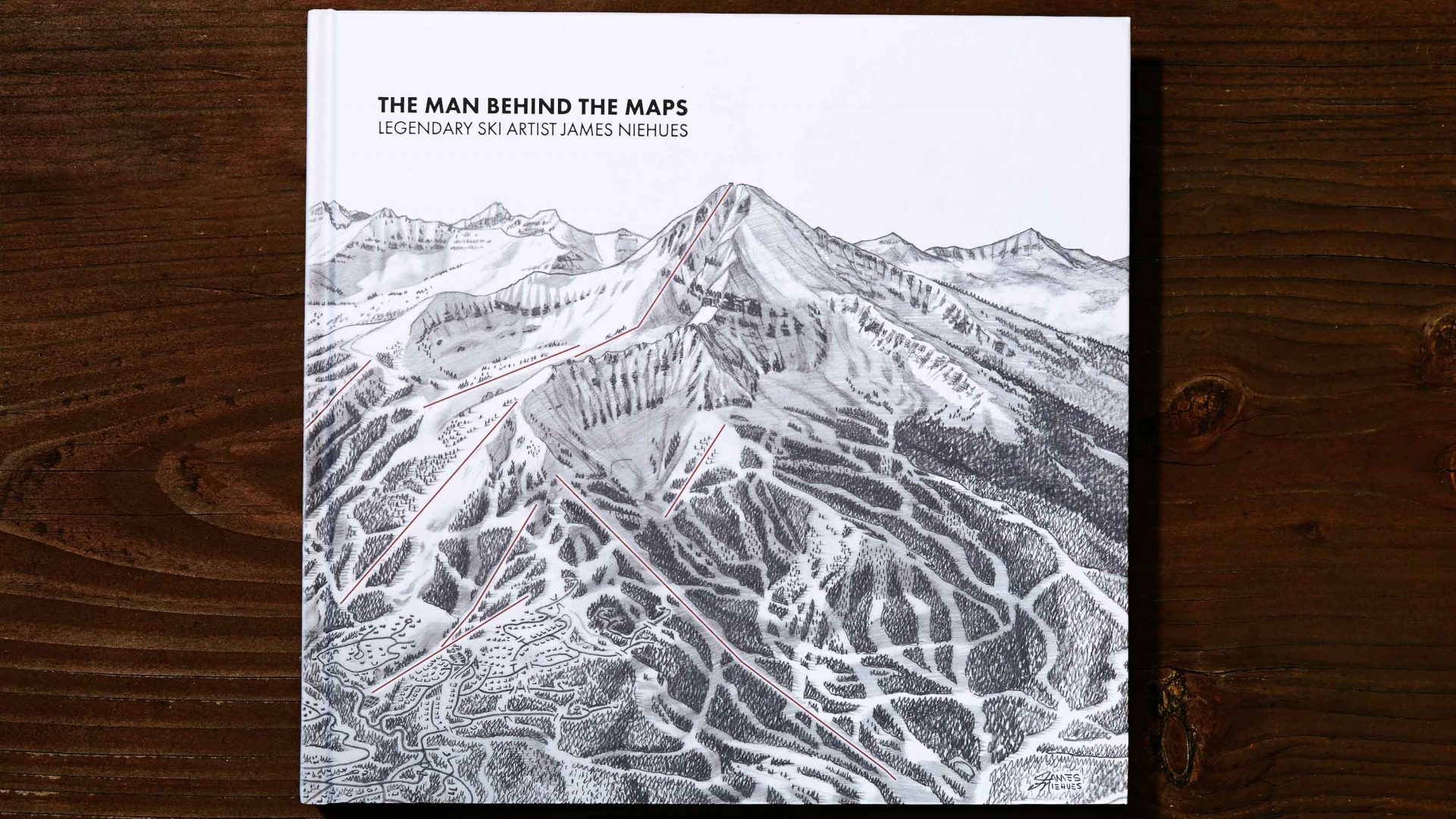

More commissions followed. Word got around. At the time, there were only two other ski artists operating in North America, perhaps the world: Bill Brown and Hal Shelton, the legendary cartographer who had revolutionized topographical maps in the 1950s and ‘60s. But Shelton had more or less hung up his brush, and Brown was keen to explore other projects. Without really trying, Niehues had cornered the ski trail map market.

RELATED: How journalist Neil Shea unlocked the storytelling power of Instagram

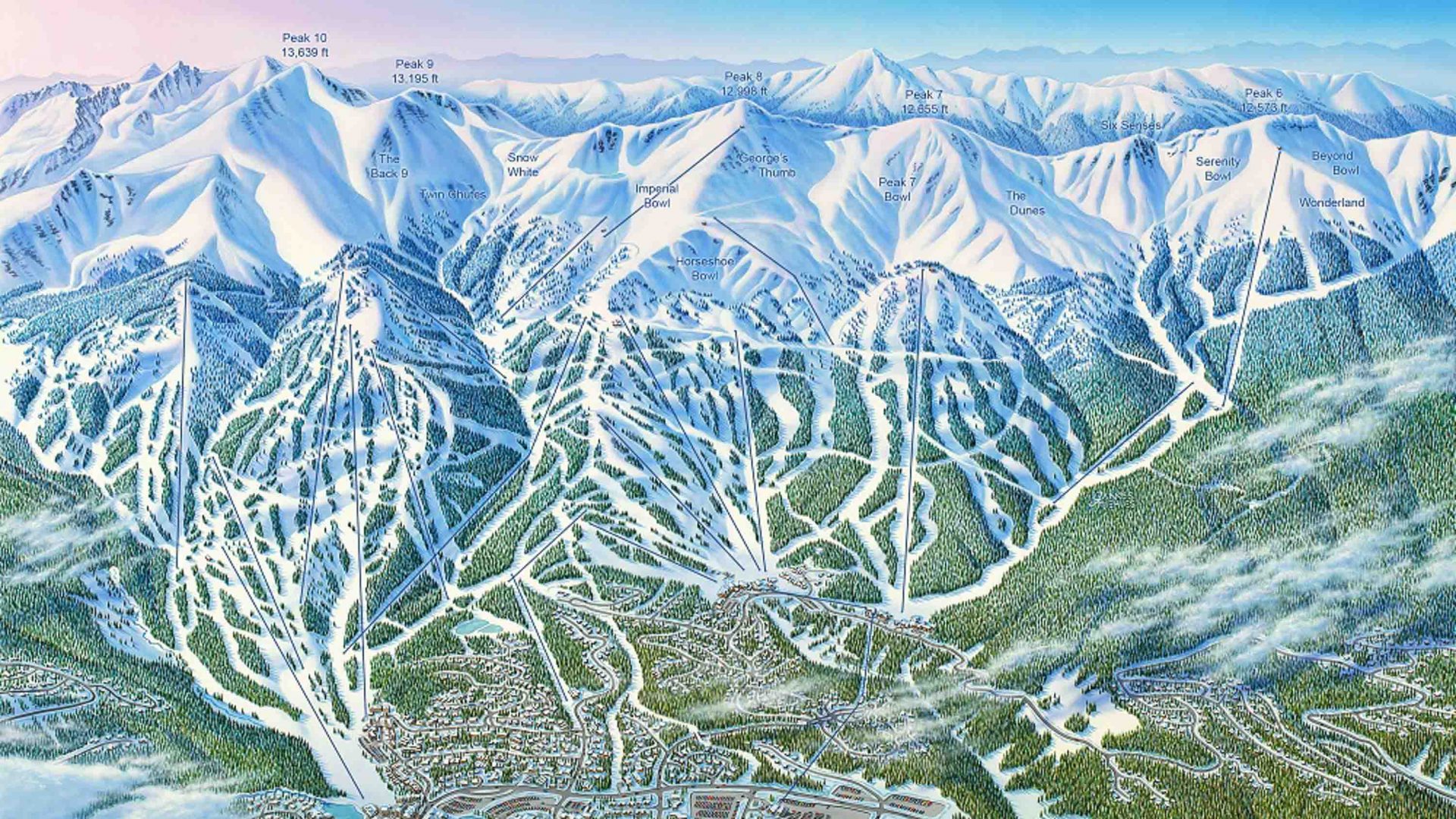

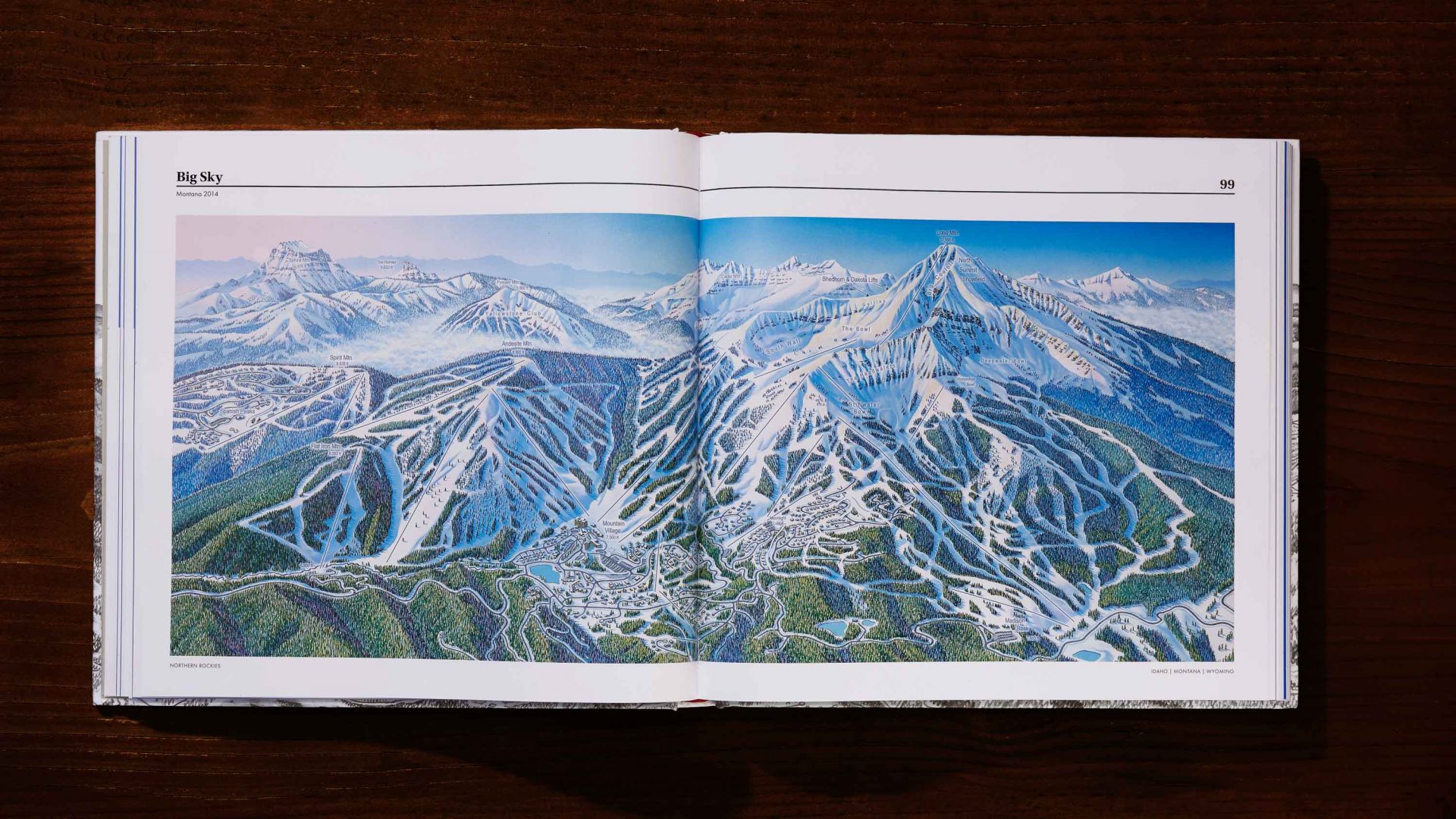

By the 1990s, he was painting 12 hours a day, seven days a week, resting his arm in a sling when it became too painful to lift the brush. “It takes about a week to sketch a large ski area, and three weeks to finish the final painting. I used to have them lined up through the summer months. Some years, I’d do 20 maps. Other years about 12.”

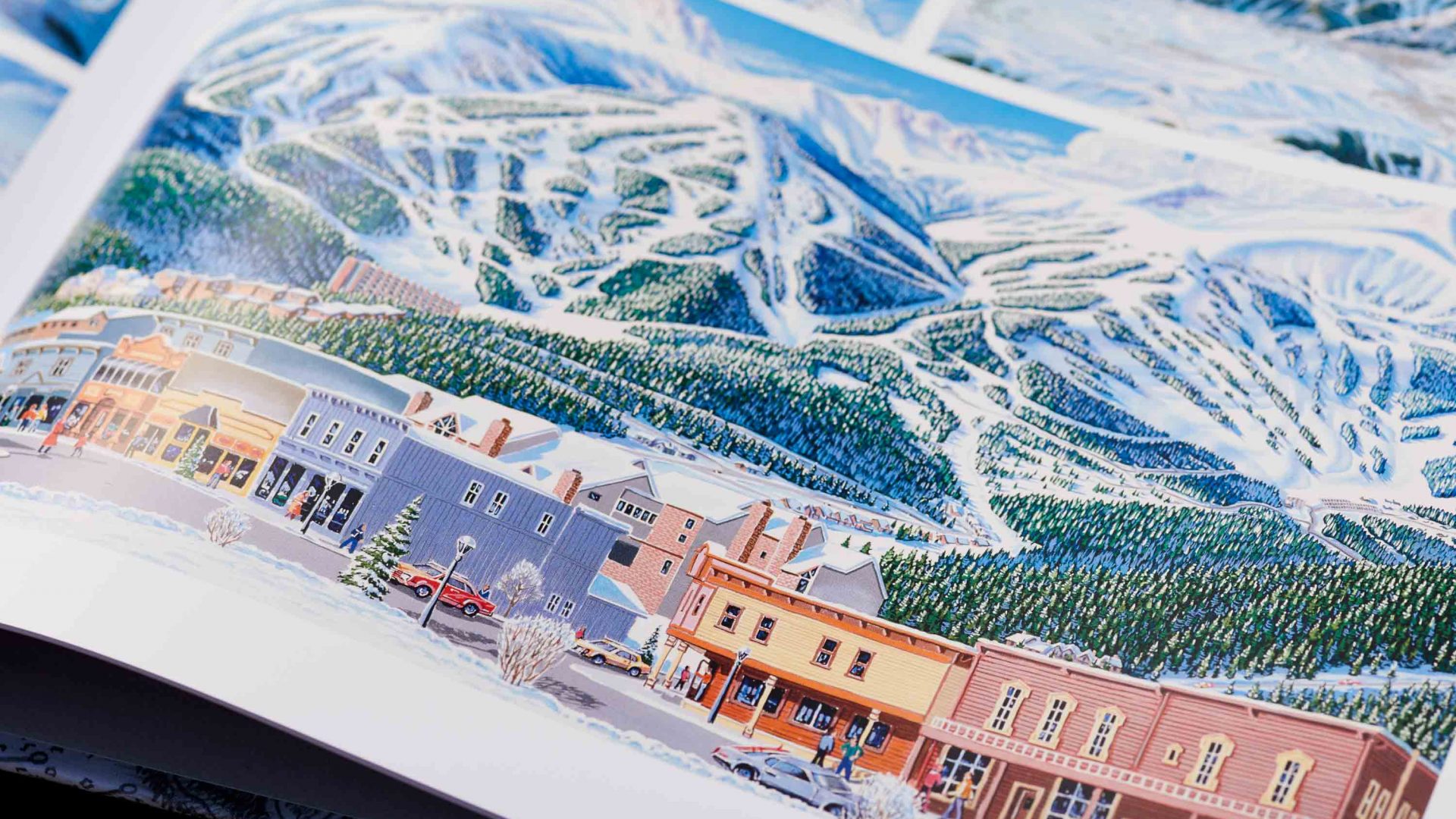

Niehues painted the trail map for Vail in Eagle County, the third biggest ski resort in the United States. He copied Winter Park onto Kodachrome slides and sent them to every ski resort he could think of, along with a note: “A quality illustration reflects a quality ski experience.”