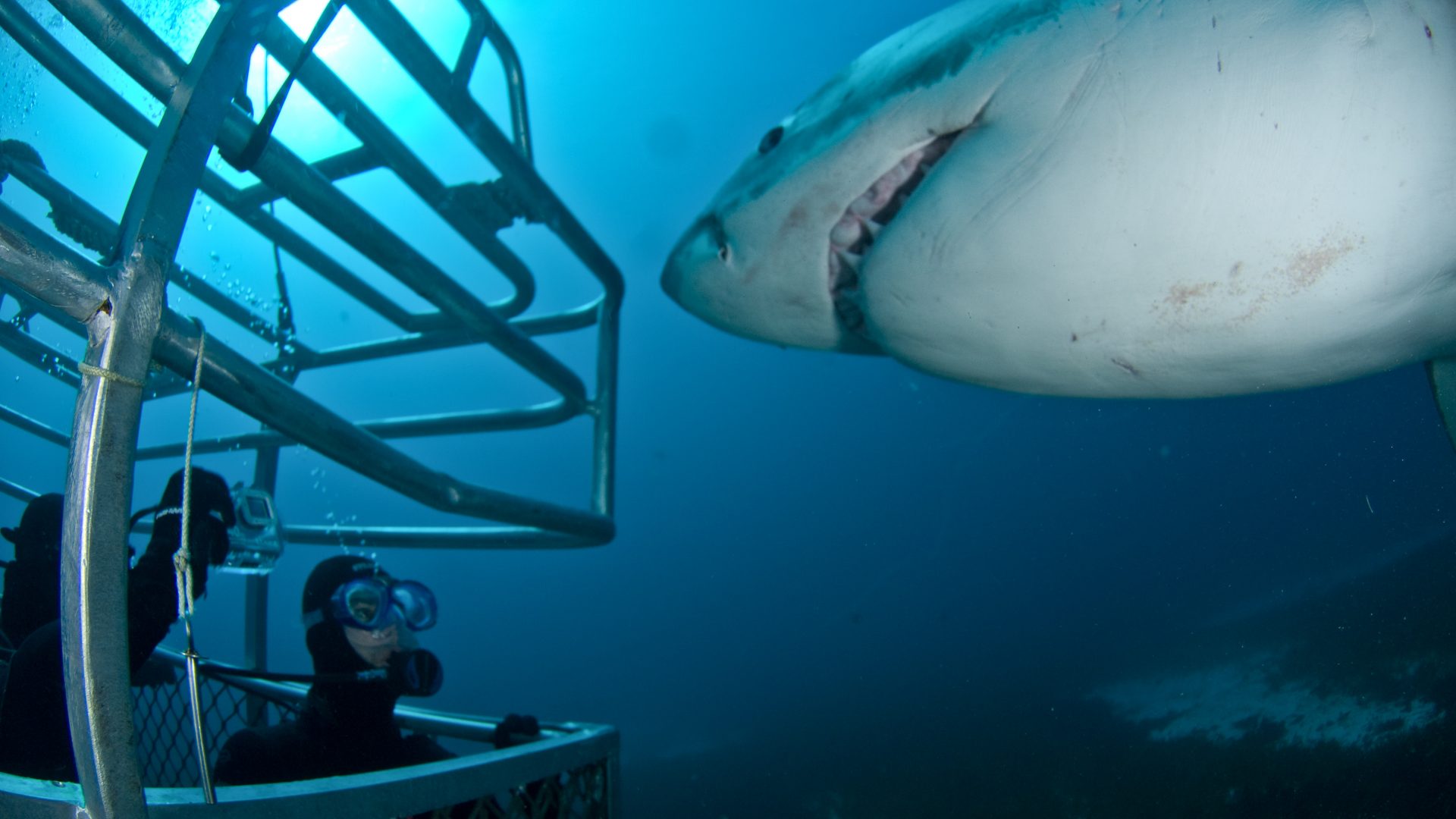

Severely bitten by a great white shark, you’d think that was it for Rodney Fox. But the attack marked the start of a new chapter—he’s now a renowned shark conservationist who pioneered modern shark cage diving.

Rodney Fox was 23 years old when he was bitten by a great white shark. Competing to retain his title as South Australian Spear Fishing Champion in 1964, he dived down for a large grouper. That’s when an immense force smashed into his side.

“I thought I’d been hit by a train,” Rodney recalls in his book, Sharks, the sea and me. “My chest was clamped, like in a vice. I was a bone in a dog’s mouth.”

Propelled violently sideways, acting on a level before thought, he jabbed his fingers into the eyes of the shark. It released him and he finned hard to the surface, too shocked for fear. Then he looked down. A gaping mouth of teeth was coming at him.